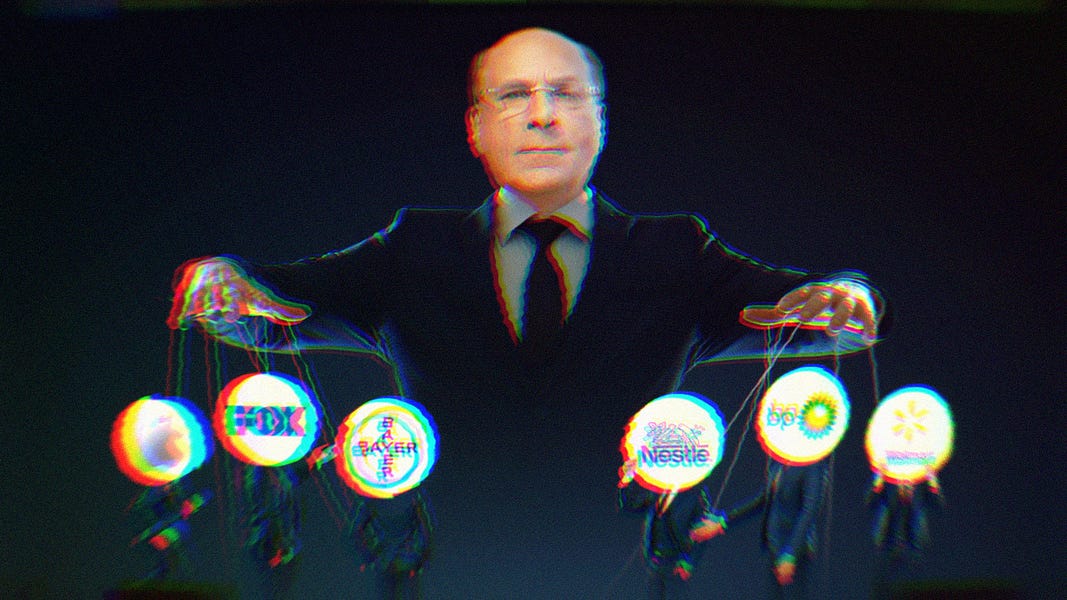

BlackRock: The Devil's Banker. Do As I Say, Not As I Do

Image Description: Larry Fink as a puppet master; the puppets are Apple, Fox, Bayer AG, Nestle, BP and Walmart.

Image Description: Larry Fink as a puppet master; the puppets are Apple, Fox, Bayer AG, Nestle, BP and Walmart.

This isn’t the hit piece you want it to be.

But don’t fret. It’s important to have an open and honest conversation about companies like BlackRock, and others that we’ll soon cover.

We’re going to sporadically populate the feed with takedowns of large institutions that have a controlling interest in our lives, whether we’re aware of them or not. The companies we’ll cover are true enablers of the capitalist and neoliberal model, and oftentimes—as in the case of BlackRock—unapologetically so. The ones who do the devil’s bidding regardless of their intentions.

BlackRock is often the subject of conspiracy theories, which makes it a titillating topic for sure. It also makes it more difficult to separate fact from fiction, even in some of the conventional coverage of the company.

-

For example, you might have heard that BlackRock is buying up single family homes and bidding up the prices, thus causing a housing crisis.

-

Or that it has ties to the Chinese government and is funneling U.S. money into blacklisted Chinese investments.

-

Or that its senior executive team is involved in a child death cult and drinking baby blood in a bid to live forever.

Sorry. That last one is QAnon.

The bottom line is, if you’re looking for a bogeyman on Wall Street, BlackRock is an easy target because it actually does have a hand, or a wallet, in every corner of the global economy.

On the flip side, BlackRock found itself as a target for Republicans for being too woke by demonizing the fossil fuel industry and pushing green and socially responsible investments. Point being, as with most conspiracy theories, there’s always a hint of truth or logic that drives these narratives. It doesn’t take much to extrapolate some wild theories when the company in question controls a platform that moves $10 trillion throughout the global economy. Yes. $10 trillion.

To do this the right way, we’ll have to debunk a few of the more salacious rumors about the company, define what BlackRock actually is and what should concern us all.

Chapter One

Bank or no bank? You decide.

Is BlackRock the devil? Or even the devil’s banker? Wait. Is BlackRock even a bank? No, no and maybe. (But it makes for a catchy title.)

That said, BlackRock is far from innocent. A company of its size doesn’t get to where it is by playing nice or being magnanimous. What I’ll argue today is that its detractors are focusing on the wrong things.

Let’s level-set with a few definitions for those who don’t work in the financial industry. For those of us who exist on the periphery of the global financial system, the jargon can be confusing. Like any industry, it has its own lingo, its own rhythm and rules. Because BlackRock occupies so much market and mindshare, it’s helpful to understand what exactly it is. Here we go:

Investment Banking

An investment bank is a financial institution that primarily acts as an intermediary. It facilitates transactions such as initial public offerings (IPO), which is when a company goes from being privately held to publicly traded. It can also act in an advisory capacity to institutions such as pension funds and other large institutions that manage large inflows of capital and investments. These companies typically make money on fees for the services they provide.

One of the things that you might have heard people like Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren advocating for is the reinstatement of Glass-Steagall. This was an ACT passed in 1933 to separate retail banking activities from investment banking activities. We’ll cover retail banking in a moment, but essentially the idea was to prevent investment banks from accessing consumer deposits to use in risky investment strategies. Basically, prohibiting them from gambling with your money. Recall from our Clinton series that this act was repealed late in Clinton’s tenure to make banks more competitive in the global financial market. Long story short, it didn’t take long for investment banks to fuck around with our money and bring the world to the brink of economic collapse.

But I digress. So these are the real Wall Street cowboys, as it were. Most often, people associate investment banking with companies like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase. The big three.

Right. So BlackRock is an investment bank.

Nope. But it owns 7% of Goldman, 6% of Morgan Stanley and 6.5% of JPMorgan Chase. Hold that thought.

Depository Institution

This is any institution that can hold onto money. There are essentially three different types. Commercial banks, which hold corporate money and typically have retail divisions for consumers. Thrifts, which are basically just savings banks. And credit unions. Credit unions are distinct because they’re actually member owned rather than corporately held.

So, when we refer to BlackRock as a bank, it’s a little misleading. BlackRock is a fiduciary, but it’s not a depository institution, a key distinction that will be important in a bit. The big depositories that people are most familiar with are banks like Bank of America, Citigroup or Wells Fargo, to name a few.

So those are banks and BlackRock is not. Got it.

Except that BlackRock owns 3.8% of Bank of America, 8% of Citigroup and 4.25% of Wells Fargo.

Ah. So not a bank. Just an owner of the banks. Makes sense.

Capital Investment Firms

Again, these exist along a spectrum as well, but are usually distinguished by having high net worth individuals as members or shareholders. That’s because the commitment of money to certain investments is typically very high, and for many years. Examples are venture capital firms that invest in the early stages of private company startups. These are high risk, high return. Private equity firms invest in the companies that made it past the venture capital stage and may or may not be on their way to going public, or just going through extreme growth. Then there are hedge funds, which are typically guided by a specific strategy and have the ability to leverage their investments.

Private equity firms are usually looking to build wealth through growth and value. By investing directly into a company, and oftentimes having significant influence over management and directors, private equity operates more like a strategic partner. Hedge funds, on the other hand, are typically in it for the short run and looking to turn a quick buck, but a big buck. They are usually less regulated and take on institutional and individual money from accredited investors that know what they’re getting into because, as the name suggests, hedge funds typically zig when the markets zag. That’s why they’re used as a hedge against the norm. Big private equity funds, the ones that really move the market, are firms like KKR, Blackstone and the Carlyle Group. These three companies alone hold about $1.5 trillion dollars in equity assets across the globe.

Okay. Finally! So BlackRock is a hedge fund. Or a private equity firm. Or... both?

No, silly. But it does own 4.2% of KKR, 3.9% of Blackstone and 2.1% of Carlyle.

Here again, we’re making our point by not making our point. BlackRock isn’t a bank, but it owns the biggest ones. It’s not an investment bank, it just owns them. And it’s not in private equity or venture capital, but it owns a chunk of the biggest players in this field as well.

So what do we call this NOT bank that isn’t a private equity venture hedge fund retail depository investment banking firm?

Glad you asked.

BlackRock is the world’s largest asset manager.

Simply put, asset managers manage money on behalf of individuals or institutions and invest them in vehicles that hold the promise of growth in value. Stocks, bonds, insurance products, etc. Along the spectrum of asset managers, there are different roles with different levels of responsibility. Like brokers. People or companies that simply place trades as an intermediary, but have no fiduciary responsibility. A fiduciary, by the way, is a person or company that is required to put its client’s interests ahead of its own. By law.

So what’s fascinating about its position as an asset management company is that BlackRock is a public company. Owned by many of the firms that they hold positions in to produce the returns that go back into the pockets of the shareholders, which are also their investors.

Get it? Quite the circular flow of money.

What I’m driving at is that conflicts of interest abound in the world of BlackRock. But before we get there, it’s worth exploring how a company that started as a division within another firm 34 years ago and was bought out 28 years ago became the largest asset management company in the world when it only went public in 1999.

Chapter Two

Birth of a giant.

Larry Fink was having a bad day. A terrible one, in fact. The darling of First Boston became a victim of his own design when his division at the company lost $100 million in one quarter in 1988. This son of a shoe salesman who is credited alongside Lewis Ranieri for inventing the mortgage-backed security (MBS) and built a multi-billion dollar portfolio with MBS at the core, had underestimated the risk profile of his holdings. Never mind that it was a fraction of what he had gained for the firm or that the portfolio would recalibrate and go on to be an unparalleled success until the eventual collapse of the housing market. Larry Fink was kicked aside and left for dead.

But, as the saying goes, you can’t keep a good man down. Salvation lay only a few months away when a man named Steve Schwarzman came calling. Schwarzman was himself a lion in the jungle and was looking to diversify the offerings of his company. That company was Blackstone.

You mean BlackRock.

No, I mean Blackstone.

As I was saying, Steve Schwarzman was and is an icon on Wall Street in his own right. In their book King of Capital, by David Carey and John E. Morris, they detail the rise, fall and rise again of Schwarzman and his plucky band of Wall Streeters who founded Blackstone.

Blackstone was fairly original at the time. Coming off the heels of blow ups at leverage buyout firms and the cutthroat nature of exploitive investing, Schwarzman sought to create a different animal by picking the best, most profitable parts of other businesses. He focused first on advisory services, basically consulting on mergers and acquisitions, a highly profitable area because it requires no capital, just smarts.

While it was slow going in the beginning, he cultivated a solid reputation, and that part of the business began to grow and fund their other interests. Private equity was among those interests and is primarily what Blackstone is known for today. Another was asset management, and that’s where our protagonist Larry Fink rejoins the story.

As Carey and Morris write:

“In February 1988, Blackstone corralled Laurence Fink… A pioneering financier and salesman, he was considered the second leading figure, after Salomon Brothers’ Lewis Ranieri, in the development of the mortgage-backed bond market. At the time, Fink was about to lose his job at First Boston after his unit racked up $100 million in losses in early 1988. But Schwarzman and [Pete] Peterson had from the start hoped to launch affiliated investment businesses and thought Fink was the ideal choice to head a new group focused on fixed-income investments.”

Fink went about building a considerable asset base within Blackstone. Forgotten was the $100 million loss at First Boston, but new troubles were on the horizon for Fink. Schwarzman and Fink were similarly built in terms of competitiveness, and the two would eventually look to part company. It’s not one of those famous Wall Street fallout stories, but it became evident that the company wasn’t big enough for both men.

So in 1994, Blackstone split off its asset management division, BlackRock, and sold it to PNC Bank for $240 million. It was a decent chunk of change, and Fink’s BlackRock was managing more than $23 billion in assets at the time. Just five short years later, BlackRock would again be spun out, but this time completely on its own through an IPO. Few could have imagined just how far Fink would go in building the base of assets, however. Especially Schwarzman.

As Carey and Morris write:

“BlackRock went on to surpass Fink’s headiest dreams. Over the next dozen years it grew into an investment empire comprising $1.2 trillion of assets, mostly fixed-income and real estate securities, reshuffled its ownership, and went public in 2006. By 2010, BlackRock was the world’s biggest publicly traded money manager, twice as big as its nearest rival.”

In 2008, there was a financial crisis looming, and the incoming Obama administration wound up pulling Fink inside the most delicate conversations to see how the Wall Street scion—once cast aside for improperly assessing the risk of his portfolio—could help assess the riskiest assets on Wall Street. There, among the biggest names in finance and government, was son of a shoe salesman, Larry Fink, who was able to maintain a remarkably low profile thus far considering the rapid ascension of his firm.

A Vanity Fair article from 2010 was one of the first real public outings of Fink as a master of the universe. Prior to this, he was extremely well-known on Wall Street, but hardly part of the high society social scene or a household name by any stretch. That was all about to change during the financial crisis. As the article notes:

“At the height of the disaster, when the American economy was on the brink, it was to Fink that Wall Street’s C.E.O.s—including J. P. Morgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon, Morgan Stanley’s John Mack, and A.I.G.’s Robert Willumstad—turned for help and counsel. As did the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, whose top officials turned to Fink for advice on the financial markets and assistance on the $30 billion financing of the sale of Bear Stearns to J. P. Morgan, the $180 billion bailout of A.I.G., the $45 billion rescue of Citigroup, and those of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac at $112 billion and growing.”

The reason Fink was the go-to man at the time went beyond just his personal acumen. Fink had another secret weapon. A technology solution launched in 1999—the same year BlackRock went public—that the firm had been refining each and every year. A risk assessment platform named Aladdin.

Aladdin, broadly, is a technology platform that assesses portfolio risk based upon its assets and multiple exposure inputs. As a recent Financial Times (FT) article notes, “Today, it acts as the central nervous system for many of the largest players in the investment management industry and, as the Financial Times has discovered, for several huge non-financial companies.”

This latter point is an important distinction. We live in an era of conglomerates and behemoths. And some of these, such as Apple, Google and several sovereign wealth and pension funds, rely on Aladdin to manage their risk profile and balance their portfolios. Again, FT:

“Today, $21.6 trillion sits on the platform from just a third of its 240 clients, according to public documents verified with the companies and first-hand accounts. That figure alone is equivalent to 10 percent of global stocks and bonds.”

This platform adds a crucial element of diversification to BlackRock’s holdings. No longer is it simply an asset manager, it’s a tech company. Not only does BlackRock manage the flow of trillions in investments into its ETFs, which stands for Exchange Traded Funds (essentially, large pools of capital that invest into sectors of the economy, certain indices or markets), it also provides the risk assessment tools for competitors and clients alike. Given the sheer size of its influence over the global financial system, it would make sense that BlackRock would come under an intense level of scrutiny. But the opposite is true.

During the negotiations in the financial crisis, policymakers attempted to reign in the influence of financial institutions that were “too big to fail.” But Larry Fink was behind closed doors in the White House when these decisions were being made.

Because BlackRock wasn’t considered a fiduciary, meaning they only interact with funds as they pass through their systems and don’t actually hold onto funds, it was determined to be exempt from such scrutiny.

FT highlights some of the risk associated with this decision to allow BlackRock to operate outside of such regulatory purview:

“Aladdin’s sprawling influence has prompted fears that it, or BlackRock, could act as a chokepoint if it either faced a shock—a cyber attack, a rogue line of code or a sudden crisis for the company—destabilizing the financial system.”

Moreover, because it operates as a black box of sorts, BlackRock operates somewhat on the honor system that it will provide honest assessments of the market, certain indicators and even understand the opaque decisions being made by algorithms on the other side of its tools. Now, consider the layers of conflict that exist. Take Apple, for example. BlackRock is one of the major owners of Apple through its ETFs, as well as direct investments it maintains on its balance sheet. As such, it has a significant say in the boardroom. Apple is also a customer of Aladdin. Myriad investment firms purchase shares of Apple through BlackRock, or independently, while using Aladdin to determine the level of risk. Now, insert literally thousands of the world’s largest companies, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds for Apple, and a troubling pattern emerges.

Chapter Three

Just how big is BlackRock?

Money.

Let’s start with their own words. Here’s an excerpt from their 2021 annual report:

“We went from serving a handful of clients in one country to thousands of clients in more than 100 countries. Our employees have grown from 8 to 18,400. And since our IPO in 1999, we have generated a total return of more than 9,000% for our shareholders, well in excess of broader markets.

“We generated $540 billion of net inflows in 2021, representing a record 11% organic base fee growth. Importantly, our growth was more diversified than ever before. Our active platform, including alternatives, contributed $267 billion of net inflows representing nearly half of total net inflows. ETFs remained a significant growth driver with record net inflows of $306 billion. And our technology services revenue grew by 12% reaching $1.3 billion.”

Once again, we need to distinguish between the money that flows through their platforms and the revenue they generate on fees associated with the revenue. There’s a tendency to generally quote the $10 trillion figure that flows through BlackRock or $21 trillion that touches Aladdin. Don’t get me wrong, these are staggering sums. But that’s not revenue.

Their revenue for 2021 was an impressive $19 billion, up from $16 billion in 2020 and $14 billion in 2019. What’s even more impressive to me is its efficiency. On the $19 billion in revenue in 2021, it posted a $7.4 billion operating profit, which is upwards of 38%. BlackRock is a fucking ATM.

Now, back to the money it controls and the flows it influences. With $10 trillion in assets under its control, BlackRock is the largest asset manager in the world. That’s more than the gross domestic product of every single country, with the exception of the United States and China. BlackRock, Vanguard and UBS, the top three money managers “cast more than 25% of votes at corporate shareholder meetings.”

Influence.

To get a sense of its power, BlackRock has hired dozens of former government officials (at one point, the count was at 84), effectively giving it immeasurable influence over public policy. Perhaps not surprising to anyone familiar with the revolving door between the government and corporations, the Biden administration has tapped several former and current BlackRock employees for influential economic roles, including none other than BlackRock’s co-founder and CEO Larry Fink.

According to Business Insider:

“Former BlackRock investment executive Brian Deese leads Biden’s National Economic Council, effectively serving as his top advisor on economic matters. Biden also tapped Adewale ‘Wally’ Adeyemo, a former chief of staff to BlackRock chief executive and longtime Democrat Larry Fink, to serve as a top official at the Treasury Department. Meanwhile, Michael Pyle, BlackRock’s former global chief investment strategist who had worked in the Obama administration before joining the firm, serves as chief economic advisor to Vice President Kamala Harris.”

Per Bloomberg:

“The company is now seen as one of Wall Street’s key conduits to the power center in Washington—a tag that was more closely associated with Goldman Sachs Group Inc. through prior administrations.”

They outflanked Goldman Sachs. Now that’s saying something.

As for the employment of former government officials, here’s what we know: Many of the ex-public officials served as regulators and central bank officials. One of the likely reasons for doing this, although they won’t admit it, is to ward off regulations. According to The Wall Street Journal, in 2014, BlackRock executives “obtained a copy of a confidential Federal Reserve PowerPoint presentation that argued part of the giant money manager could pose the same financial-system risk as big banks.”

BlackRock was particularly concerned about two slides that read: “If it looks like a bank, quacks like a bank…”

That set off an aggressive campaign by BlackRock to kill any potential regulations, at all costs. As the Journal reported:

“The presentation—which BlackRock told members of Congress contained wrong information—galvanized the firm around a crusade to elude more aggressive oversight from the Fed.”

BlackRock was historically non-existent on the lobbying scene, as the aforementioned Journal article lays out. But things changed around the time of the Great Recession when the government had no choice but to institute a regulatory regime, the most notable being the Dodd-Frank Act (which was neutered by the Republicans in 2018).

According to OpenSecrets, a nonprofit that tracks corporate donations and lobbying efforts, BlackRock spent less than $200,000 on lobbying in 2004 and employed only a pair of lobbyists. In 2009, its lobbying budget more than doubled compared to seven years earlier, and it began to assemble a larger pipeline of lobbyists. By 2011, BlackRock was spending about $2.5 million on lobbying.

The behemoth asset manager did not take kindly to comparisons likening it to big banks, especially in the context of regulations. In 2013, the Wall Street Journal reported that BlackRock and similar companies were “alarmed” by a report from the Treasury Department’s Office of Financial Research that read, in part:

“Some activities highlighted in this report that could create vulnerabilities—if improperly managed or accompanied by the use of leverage, liquidity transformation, or funding mismatches—include risk-taking in separate accounts and reinvestment of cash collateral from securities lending.”

The government came calling again during another crisis; this time being the pandemic. After being enlisted by the Fed to prop up the corporate bond market two years ago, the financial law expert William Birdthistle referred to BlackRock as the “fourth branch of government.”

Chapter Four

The ESG Hullabaloo.

One of only two times we’ve referenced BlackRock on Unf*cking the Republic was in our Problem with Conscious Capitalism episode. In that show, we were highlighting the rampant greenwashing on Wall Street with firms claiming Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) initiatives. Essentially, calling bullshit on the trend of large companies that do bad things to society and the environment, but spend their way to absolution through programs like carbon offsets, energy efficiency and charitable donations. Here’s what we said:

“Let’s look at BlackRock. Huge firm, top of the top. They, too, have an ESG fund. Let’s see… performance, key facts… ah yes, top 10 holdings. We’ve got Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Facebook, Alphabet Class C, JPMorgan Chase, Tesla, NVIDIA and… Johnson and Johnson.

Yes, I do know it’s incredibly gauche to quote oneself. But I’m just trying to point out that I’m consistent, if nothing else. Anyway, here’s what BlackRock itself has to say about its ESG efforts:

“Environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing is about investing in progress and recognising that companies solving the world’s biggest challenges can be best positioned to grow. It is about pioneering better ways of doing business and creating the momentum to encourage more people to opt into the future we’re working to create.”

“Our investment conviction is that climate risk is investment risk, and that integrating climate and sustainability considerations into investment processes can help investors build more resilient portfolios and achieve better long-term, risk-adjusted returns.”

“We believe that society is on the cusp of transformational change towards sustainability. Companies, investors and governments must prepare for a significant reallocation of capital. BlackRock’s sustainability strategy focuses on two structural themes driving this change: transition finance and stakeholder capitalism.”

Here’s where it gets a little tricky and we find some strange bedfellows. The dark money group Consumers’ Research is running ads against corporations that perform what it calls, “woke capitalism.” Yep, grievance-obsessed, culture war evangelist Republicans are coming after capitalism—welcome to the party! (Or maybe not.)

Consumers’ Research is specifically targeting BlackRock for purportedly betraying their clients by calling for divestment in fossil fuels and other ESG activities. In a so-called “Consumer Warning” released in August, the group inexplicably blamed BlackRock and its CEO Larry Fink for rising energy prices:

“Using trillions in investors’ money, CEO Larry Fink waged war on America’s energy companies, pushing a progressive climate agenda that has crippled U.S. energy production and left consumers with a hefty bill.”

The anti-ESG culture war comes as more than a dozen GOP states claim BlackRock is violating its fiduciary responsibility. Two states—Texas and West Virginia—have effectively banned BlackRock and other ESG companies from doing business with them. West Virginia’s ban includes five firms, including BlackRock and JPMorgan Chase. This is particularly hilarious considering that JPMorgan Chase continues to be the largest financier of fossil fuels out of any major bank in the world—to the tune of more than $380 billion between 2016 and 2021.

As for our friends at BlackRock, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit newsroom, reported on a meeting BlackRock executives had with Texas’ oil and gas “regulator” amid criticism of its ESG efforts:

Here’s what the outlet reported:

“In January, BlackRock sent a team of senior staff – including Dalia Blass, its head of external affairs – to meet Wayne Christian, a former Republican legislator who has chaired the state’s oil and gas regulator since 2016.

“In his follow-up email to Blass, Christian noted the BlackRock team had said their environmental, social and governance (ESG) initiatives had been misrepresented by the media and that the company was ‘supportive of the oil and gas industry and merely offers ESG energy-related investments because of client demand.’ He questioned BlackRock on the contradictions between these reassurances and its public stance on climate issues.

“Blass had already written to Texas officials to highlight BlackRock’s support for the fossil fuel industry. ‘We are perhaps the world’s largest investor in fossil fuel companies,’ she wrote. ‘We want to see these companies succeed and prosper.’”

Among the most outspoken opponents of ESGs is none other than Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, the unofficial spokesperson for the GOP's culture war army. DeSantis was responsible for the Florida State Board of Administrators decision earlier this summer to prohibit the “furtherance of social, political, or ideological interests” in investment policy matters.

Here’s what DeSantis had to say after his proposal was adopted: “With the resolution we passed today, the tax dollars and proxy votes of the people of Florida will no longer be commandeered by Wall Street financial firms and used to implement policies through the board room that Floridians reject at the ballot box.”

Let’s just say we’re not buying Ron’s war on Wall Street. Why? Let’s take a look at his campaign contributions. From Politico: “Top Wall Street executives are pouring tens of millions of dollars into the Florida Republican’s upcoming reelection campaign,” the outlet reported in August. Wall Street is obviously hedging its bets in the event DeSantis becomes the MAGA heir apparent if his political mentor from afar—maybe-soon-to-be-indicted Donald Trump—decides not to run, which is unlikely given he’s, well, Trump.

As with so many idiotic culture war clashes that bleed into the political discourse, ESGs have become the new way for officials on both sides to prove their ideological bonafides. Apparently owning the libs on climate is more important to this era’s brand of Republican politics than the free market principles they’ve for so long fetishized. As we mentioned, more than a dozen states have moved to erase corporate ESG policies. Democrats, on the other hand, have been bullish on the idea of having pension systems divest from fossil fuels, with Maine’s state legislature becoming the first to do that with its move in 2021 to divest $1.3 billion in such investments over five years.

Take this with a grain of salt perhaps, but a Morgan Stanley white paper published in 2019 found “no financial trade-off” when embracing ESGs. Morgan Stanley compared sustainable funds, or ESGs, to traditional funds from 2004 to 2018—10,723 in total:

“We found that sustainable funds provided returns in line with comparable traditional funds while reducing downside risk. What’s more, during a period of extreme volatility, we saw strong statistical evidence that sustainable funds are more stable. Incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into investment portfolios may help to limit market risk.”

Its analysis also found sustainable funds to be less risky, noting:

“Sustainable funds experienced a 20% smaller downside deviation than traditional funds. This was a consistent and statistically significant finding.”

ESG funds have steadily gained in popularity over time. Between 2004 and 2018, sustainable funds grew 144%, according to Morgan Stanley. To believe the GOP's line of thinking, so-called “woke” investing would’ve existed well before the term was bastardized by Republicans and well before the Paris Agreement in 2016. That they lead with Paris as a jumping off point for such investment decisions is belied by the data.

Whether money managers like BlackRock are actually committed to such ideals is another matter entirely.

Chapter Five

Bring it home, Max.

BlackRock and its founder present an interesting conundrum in the world of finance and, frankly, in our daily lives. As Wall Street titans go, he’s pretty conscientious. But the fact that he’s in the position of emperor where finance is concerned is problematic in and of itself. And I’ll get there in a second. But first, as I mentioned at the beginning of the episode, it’s important to distinguish between conspiracy and reality.

The first big conspiracy surrounding BlackRock in progressive circles is that it has somehow contributed to the housing crisis. Perhaps a case can be made indirectly, but in terms of deliberate attempts and direct investments, this theory doesn’t hold water. First off, there’s a small case of mistaken identity that can be found in the trove of faux online documentaries that attempt to draw a straight line between BlackRock and the purchase of single family homes during the housing crisis. That’s Blackstone, the private equity firm that birthed BlackRock, and only marginally so.

In fact, BlackRock even has an entire page on its website dedicated to dispelling this myth. Obviously, we’re not going to take corporate propaganda at face value. Pouring through their filings and looking at real reporting on the matter reveals something closer to the truth.

Even The Atlantic took great pains to clear up the confusion and point to housing regulation and other investment firms as the real culprits, saying:

“The U.S. has roughly 140 million housing units, a broad category that includes mansions, tiny townhouses, and apartments of all sizes. Of those 140 million units, about 80 million are stand-alone single-family homes. Of those 80 million, about 15 million are rental properties. Of those 15 million single-family rentals, institutional investors own about 300,000; most of the rest are owned by individual landlords. Of that 300,000, the real-estate rental company Invitation Homes—in which BlackRock is an investor—owns about 80,000. (To clear up a common confusion: The investment firm Blackstone, not BlackRock, established Invitation Homes. Don’t yell at me; I didn’t name them.)”

Another popular story is that BlackRock is a back door to Chinese government control of U.S. companies and Wall Street. Again, this is a little dubious, but there’s a kernel of truth. BlackRock was one of few firms that was able to negotiate a waiver to invest in a Chinese conglomerate. Unusual? Yes. Devious? Not as much as detractors would like it to be.

But there are areas that should raise some red flags. For example, the other time we referenced BlackRock on UNFTR, and that’s with respect to student debt. Recall that we covered the evil that is Sallie Mae. When we pulled Sallie Mae’s proxy report, we found that none other than BlackRock owned an 8.3% stake in the company.

This reveals a different disturbing pattern outside of BlackRock’s outsized influence over politicians, regulators, competitors, mega corporations, pension funds and nations. And that’s its strategy of profiting from misery. The examples are everywhere.

Like major stakes in conservative media outlets.

Yes, even the outlets hedging their bets on a DeSantis future have to tread lightly around Fink, who often appears as a guest on business shows. BlackRock owns a 7.5% share in Sinclair Broadcasting, one of the worst examples of right wing broadcast media. It also owns 12.4% of Fox Corporation. But it doesn’t end with just conservative media. Along with Vanguard, the pair of asset managers are the top two owners of juggernaut media entities, including Time Warner, Comcast, Disney and News Corp, which collectively represent 90% of the media ecosystem in the United States.

And companies that do bad things all over the world.

Nestle recently became a big customer of BlackRock when it moved its pension fund management to the firm. Interesting, considering BlackRock recently purchased 75,000 shares of Nestle in July of this year.

Want more? It owns:

-

265,000 shares of Bayer AG, formerly Monsanto

-

2.2% of Walmart with an $8 billion stake

-

A 7.1% stake in McDonald’s

-

4.1% of Dow Chemical

Honestly, the list goes on and on for pages. This information is all readily available because public companies are forced to disclose “beneficial interests” (meaning more than 5%) in other companies. They must also disclose interests that equate to less than 5%, but those are more difficult to find. And remember that it’s not just the interest through their EFTs and other funds, they have an enormous pile of cash used to manage direct investments as well. About the only thing they don’t have is checking accounts.

It also owns significant stakes in war profiteers Lockheed, Raytheon, General Dynamics and Northrop Grumman. Ironic, considering the first few pages of Larry Fink’s letter in the annual report last year was dedicated to criticizing Russia for invading Ukraine. Cool.

Do as I say, not as I do.

Fink regularly appears in interviews talking about creating a better future and praising the system of capitalism. He’s a firm believer in market solutions and views his principled stance on ESG as evidence not of manipulation, but based in the logic of free market capitalism. I don’t have a problem with that. He’s not a Marxist economist or a progressive. He sees great opportunity in a clean energy future. And that’s fine.

The problem is that we appear to be on his timeline.

Another principled stance that I align with somewhat is his feeling toward immigration. Time and again, Fink lobbies for a more reasonable immigration policy because he understands the value of increasing the workforce. He sees this as stifling economic growth in much the same way that Milton Friedman did. #FMF

Of course, here’s the thing. It’s not that they give a shit about a fair and equitable immigration policy, it’s just that they believe in letting people into the country to take jobs at abusive wages so the rest of us can enjoy open restaurants. His fear relates to wage inflation due to full employment. Again, driving to the same result with very different intentions.

So one might think that living on Larry’s timeline is okay because he’s the least bad option as America’s shadow emperor. But, when pressed on difficult issues, Larry will always land on the side of capital and profit rather than principle. One of the rare times Fink was challenged on a broadcast (because, remember, in a roundabout way he’s technically the boss of the networks) was on CNBC when he was asked to defend his position on Saudi investments after it was determined that the Saudi government had murdered and dismembered Saudi born journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi, who was a long-term American resident.

Fink deftly dodges the discussion by essentially saying bad shit happens everywhere, so we have to choose our battles wisely. The life of a journalist and U.S. resident wasn’t enough to move Fink to divestiture, just as it wasn’t enough to stop Biden from selling arms to the Saudi government.

Do as I say, not as I do.

The bottom line to Fink is the bottom line. The bottom line to the rest of us where he and others like him are concerned is that size matters.

A sustainable future is possible if we want it. But where so many important areas of the economy are concerned, getting there will be very much on Larry Fink’s timeline. And while he talks a great game, we all know how this turns out.

Your student debt is a line item in his P&L.

The murderous Saudi regime is a partner in the boardroom.

War and weapons are big business.

All seeing technology that aggregates the world data and mitigates risk means that only catastrophe will change the investment equation into fossil fuels. And that means it will be too late.

Larry Fink took a seat at the table and traded his platform and expertise for a free pass. And now, he’s too big to fail. Best we stop looking for conspiracies because the reality is far more terrifying.

Do as I say, not as I do.

No matter which camp you’re in, ESG is a scam.

Larry Fink is the unelected president of the nation.

It’s time to regulate BlackRock.

Here endeth the lesson.

Max is a political commentator and essayist who focuses on the intersection of American socioeconomic theory and politics in the modern era. He is the publisher of UNFTR Media and host of the popular Unf*cking the Republic® podcast and YouTube channel. Prior to founding UNFTR, Max spent fifteen years as a publisher and columnist in the alternative newsweekly industry and a decade in terrestrial radio. Max is also a regular contributor to the MeidasTouch Network where he covers the U.S. economy.