The Carter Series: Reexamining Jimmy’s Time in Office.

President Carter ran out his final year in office from the confines of the Oval Office as he worked night and day to free the hostages in Iran. After 444 days, they were released on the day his successor was inaugurated. It was a bittersweet and undeserving end for an all-too-brief tenure. The final installment of our series examines the events of 1980 and offers some final reflections on Jimmy Carter the man, and his legacy.

AT A GLANCE:

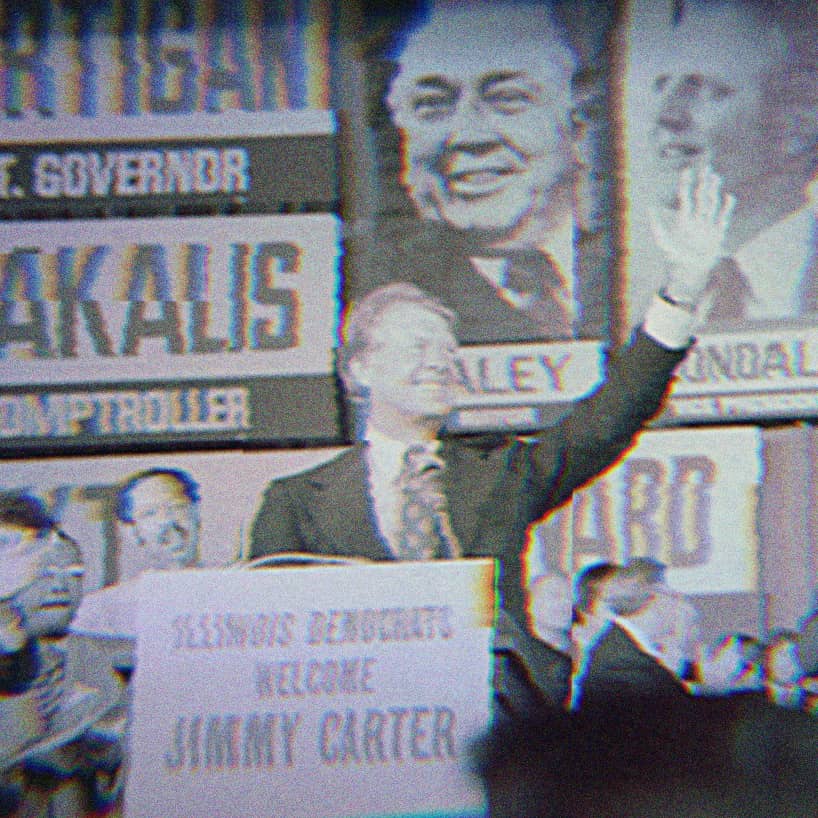

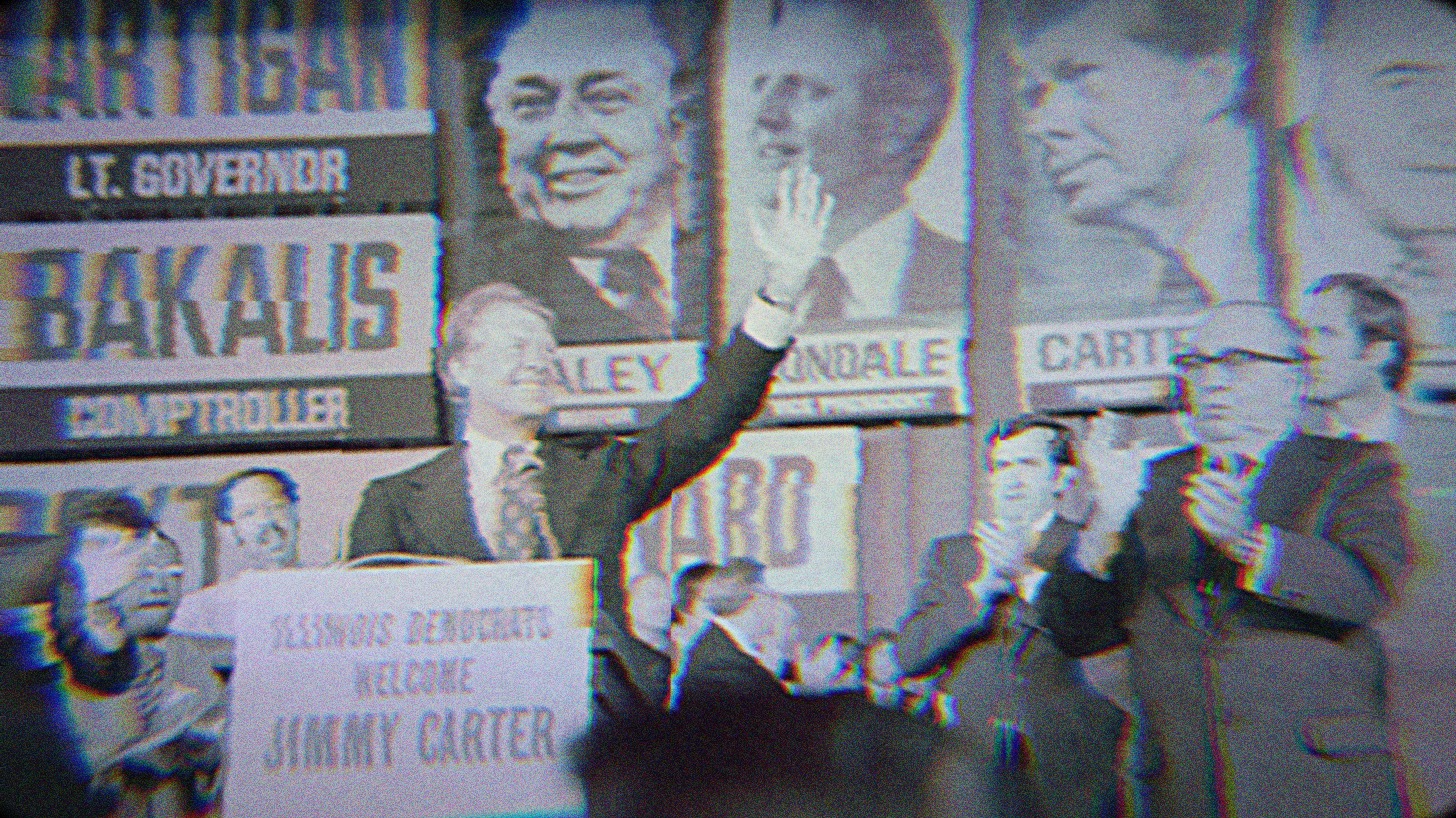

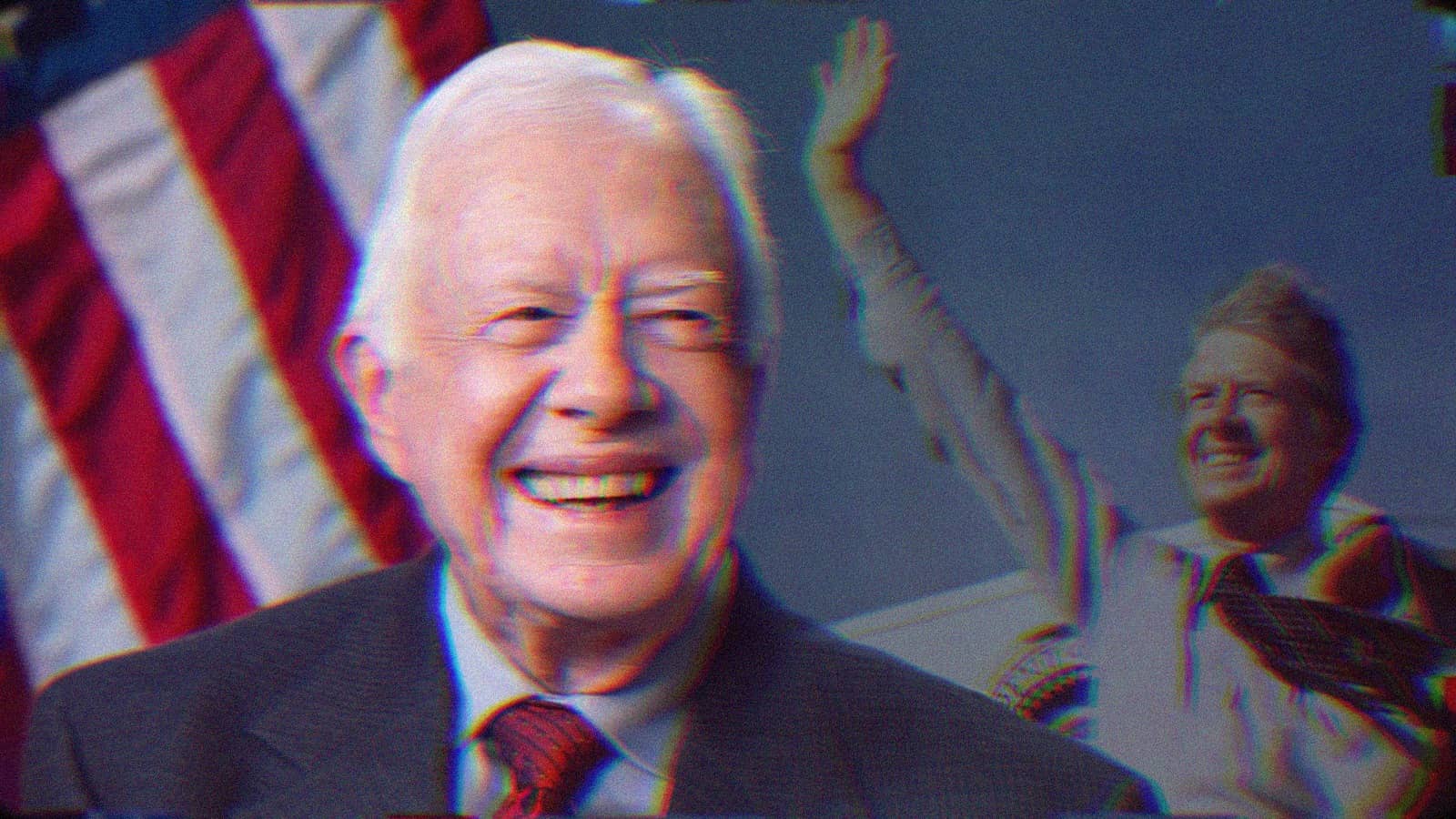

Image Description: Jimmy Carter and Mayor Richard J. Daley at the Illinois State Democratic Convention in Chicago, Illinois.

Image Description: Jimmy Carter and Mayor Richard J. Daley at the Illinois State Democratic Convention in Chicago, Illinois.

Part One: A Good Old Boy Bids for the White House.

Summary: Today, we begin our look back at the brief but remarkable tenure of President Jimmy Carter. The late ‘70s is a fascinating period on a number of levels. Civil Rights groups had fractured into several pieces, the Vietnam era had come to a disgraceful close and the economy was beginning to falter after more than two decades of astounding post-war growth for the middle class in particular. The GOP’s grip on Washington was tenuous after Nixon’s resignation, and the country wasn’t sure whether Ford was up to the task. For their part, Democrats were still healing from the ‘68 Convention and being sidelined by Nixon’s GOP. Out of the fog came a slow talking southern boy named Jimmy who shocked the world and secured the Democratic nomination for president. This is his origin story.

I’ve been struggling to find a narrative thread on the Carter years and become increasingly fascinated by this time period in attempting to do so. There are so many contradictions between the mythology cultivated by Republicans and the brief period the world’s most powerful nation was run by a former peanut farmer and one-term governor of Georgia. The things I find objectionable about the Carter years are the things not often addressed. The worst aspects of what many consider to be a failed presidency stand as beacons of achievement in hindsight.

Most would consider James Earl Carter to be a simple man. To some, he was overly pedantic. To the elite New England Democrats, he was boorish. And oh so Southern. Then again, even his detractors consider him to be an honest man. Albeit, overmatched by the job. Too small for the moment. But, honest. In reality, he’s far from simple. But he is, and always was, unflinchingly honest. Perhaps, to a fault.

There are a few reasons for putting the Carter years under a microscope. First, since Biden’s inauguration, the comparisons have been plentiful.

“The president is reportedly worried about parallels that are being drawn between him and the Carter administration. We’ve drawn those parallels several times ourselves. The thing is, if there is a parallel, maybe we should be happy because the Carter era ended with Ronald Reagan.

- Stuart Varney, Fox Business speaking with Larry Kudlow

“You can’t ignore the similarity, right, when you bring up Carter. There was crippling inflation under Carter. There’s crippling inflation under Biden. As you mentioned, that poll you just showed, only 5% of the voters see the economy as excellent, which by the way, is the way the White House describes our economy right now. So they’re completely out of touch. You had skyrocketing gas prices and long lines under Carter. Record high gas prices under Biden. America appears to be weak to our adversaries under Carter. It appears now to be weak under Biden. We saw what’s happening in Afghanistan, what’s happening in Ukraine. What China may do with Taiwan under Biden. But Carter didn’t have a self-inflicted border crisis. Biden does. Or a fentanyl crisis. Biden does. And, in the end, Carter lost 44 states when running for re-election.” -Joe Concha, on Fox & Friends First

Circumstantially, it’s not necessarily a terrible argument. Trouble with Iran. Further escalations with Russia. Multiple economic shocks leading to high inflation. Navigating a fractured country after a scandal-laden presidency. Tension with China over Taiwan. Israeli settlements frustrating Middle East peace talks. Increasing indebtedness in Latin American economies. It’s all very familiar from a headline perspective.

But we’re a vastly different nation than we were during the Carter years, and Joe Biden is a markedly different man. There are similarities on the surface. Both are men of faith. Devoted public servants. And, by all personal accounts, incredibly loyal. As far as I can tell though, that’s where the similarities end.

Two remarkable notes about Jimmy Carter is that he was elected 46 years ago and is still alive. That’s nearly half a century ago. Another remarkable thing about this is that Joe Biden had already been in the Senate for four years when Carter was elected.

So, if I don’t believe in the comparisons, why highlight the Carter years so extensively right now?

A couple of reasons.

First off, most Unf*ckers know that I believe this to be the true beginning of the neoliberal era. The moment that corporate America chose to fight back against regulations, entitlements and oversight. The moment that the Chicago School economists ascended to prominence when it appeared that Keynesian measures were failing the economy. The moment that far right figures concocted a coordinated plan of attack to infect higher education, the judiciary, local, state and federal government, think tanks, organized labor and the media with neoliberal messaging designed to break the back of the establishment.

There are many who believe we’re exiting the neoliberal era as we speak and that the dawn of a new oligarchical phase is upon us. So, there’s some degree of symbolism in covering the dawn of an era and its sunset.

Lastly, because the circumstantial parallels are indeed palpable, it’s important to reflect on the conditions that sparked conflict in certain areas to understand how they evolved. If we’re fighting on multiple fronts, be it Israel, Iran, China, Russia—or inflation and an overly aggressive Federal Reserve—surely there’s something to be gained in learning about the origins of these issues and conflicts.

For example, Roe v. Wade was codified into law just a couple of years before Carter took office. The Federalist Society was formed based upon a thesis written by Michael Horowitz during Carter’s last year in office. This same society would wind up as the central power broker in selecting Supreme Court Justices Barrettt, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh; the three far right justices that would deliberately overturn Roe 50 years after its passage.

As I’ve said many times, we cannot understand where we’re headed unless we understand from whence we came.

No matter your impression of Jimmy Carter or his time in office, the fact remains that these years are essential to building our framework of understanding of today’s political, economic and social system. After living with several texts on Carter and watching countless hours of footage, I can confidently say that he was indeed up to the task. In fact, I would go so far as to say that he might have been uniquely suited to the job at that very moment in time. That’s not to say he was perfect. Or had no missteps. There were failings, to be sure. But Jimmy Carter was in the middle of a storm that had been brewing for several years prior, and when it finally came ashore, it’s impossible to imagine any one person weathering it.

Chapter One

The Origin Story.

As of this telling, former President James Earl Carter is 98 years old. Born on October 1st, 1924 to Lillian and James in Plains, Georgia, Carter was the oldest of four children, all of whom have since passed. His parents were known to all as Earl and Ms. Lillian. By all accounts, Jimmy Carter, as he’s most often called, was a studious, shy and industrious young man who got on well with nearly everyone.

The Carters were considered rather well off for the area. While they weren’t part of the southern plantation aristocracy, they were far from poor. Jimmy’s father was a stern, hard working segregationist who many considered extremely tough, but fair. He invested everything into his farm, while also managing side hustles, military service and even a position on the county board of education later in his life.

His father was also a classic southern racist. There’s no sugar coating this fact. But he was the engine in the community that drew blacks and whites together in labor, rent and sometimes even faith. A devout Baptist, it seemed his only vice was the occasional bourbon and Friday night poker.

Lillian, on the other hand, was more outgoing and a bit of a rebel for her time. She smoked. Enjoyed drinking. Had black and white friends—much to the chagrin of her husband—and was raised a Methodist. When asked if people in their small community were upset with her choice of friends, it’s reported that Ms. Lillian remarked, “We had too much money to be ostracized.”

If the Carters were considered rich by the standards of their poor community, one person who was none the wiser was young Jimmy Carter. As the eldest son, Jimmy worked side-by-side with the black field hands that worked for his father. He would often sneak into Baptist sermons in the black church. It’s understood today that the phrase, “he didn’t see color” is absurd and demeaning. But it seemed that, at a minimum, Jimmy Carter didn’t see people of color, just people. In all that has been written or recalled in his nearly 100 years, there isn’t a person who knew him who believed Jimmy Carter had a racist bone in his body.

That’s not to say he wasn’t arrogant. Jimmy Carter was always smart. He was an accomplished student who, along with his siblings, was required by Ms. Lillian to read every night at the dinner table. This would prove to be a lifelong habit, as Carter consumed information as president perhaps more voluminously than anyone before or since.

His grades were good enough to get into community college, then Georgia Tech to study engineering. But his dream was to go to Annapolis. Earl was able to pull some strings for Jimmy to gain admission, and Jimmy Carter’s life in service began in the Naval Academy. In the middle of World War II.

Carter would go on to serve in the Navy for the next ten years. Perhaps the most important thing that happened during Jimmy Carter’s time in the Navy, however, was marrying his sister’s best friend Rosalynn in 1946. Pretty, intelligent, innocent and from Plains, Georgia as well, Rosalynn Carter remains by her husband’s side to this day. From the beginning, she was an honest and resolute truth whisperer, sounding board and guide to her husband. Perhaps the greatest White House partnership since Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, and certainly more filled with authentic love.

The couple would move throughout the country from post to post over Carter’s decade of service, and it seemed to everyone as though Carter was destined to serve his entire career in the Navy. But in 1953, Earl Carter’s body finally gave out and the Carters returned to Plains, Georgia. To everyone’s surprise, Jimmy Carter quit the Navy and took over his father’s farm. Thus, the legend of Jimmy Carter the peanut farmer was born.

“At the end of a long campaign, I believe I know our people, of this state, as well as anyone could. Based on this knowledge of Georgians, north and south, rural and urban, liberal and conservative; I say to you quite frankly that the time of racial discrimination is over.”

From Jimmy Carter’s inaugural address as governor.

This statement made during Carter’s inaugural address as governor was met with tepid applause. But it says a lot about the man and his time. Prior to winning the governor’s race, Carter had already served as a state senator and was set to run for Congress when the governor’s seat opened up in 1966.

His first attempt was a failure, losing to Lester Maddox, one of the most racist political figures in modern times. This failure set Carter back and prompted him to do a great deal of soul searching. But rather than lean into what many would consider the pragmatic instinct to appeal to a deeply southern contingency, he doubled down on his liberal principles. He ran again in 1970 and was victorious the second time around.

Carter’s single term as governor wasn’t all that notable, but it helped cultivate his governing style and persona that would lay the groundwork for a national campaign that would shock the nation. During his time in office, he collected important people that would guide him for the rest of his political career and become lifelong friends. Chief among them were Bert Lance, Charlie Kirbo and a young Hamilton Jordan. Only Jordan would accompany Carter to the White House and become an integral part of his presidency, but Lance and Kirbo were foundational to Carter’s early success and would prove to be voices of inspiration and reason as he navigated his career in the White House.

The other thing Carter took from this time was a deep understanding of retail politics and the power of populism. While many today probably don’t think of Carter in this way, at the time, he was carrying a powerful message of hope for the poor and the working class that had been lost in the wind under Nixon. Turns out, it’s exactly what the country was yearning for.

Chapter Two

A Good Old Boy bids for the White House.

“I remember when I announced for president in December of 1974, there was a major headline on the editorial page of The Atlanta Constitution that said, ‘Jimmy Carter is Running for What?’” -Jimmy Carter

When Carter announced his bid for president, very few in Washington, and in the media, took him seriously. A good old boy peanut farmer and one term governor wasn’t exactly the typical presidential pedigree. But Carter started early and worked relentlessly to build coalitions on the ground one voter, one state at a time.

By the time the campaign was in full swing and it was clear that Carter wasn’t going anywhere, he was still considered an outsider. But his message had begun to coalesce. Carter ran on a number of promises, some of which still resonate today, and others that seem wholly anachronistic.

-

He was one of the first to suggest that marijuana be reduced to a misdemeanor. Awesome.

-

He promised to curb inflation by restraining the money supply. Not awesome.

-

Carter wanted to reduce foreign imports of oil by increasing prices while giving a tax rebate for the poor. Mixed bag.

-

He favored increasing the recent auto emission standards. Cool.

-

But he also wanted to invest heavily in mass transportation. Doubly cool.

-

He promised to put in strict controls on strip mining.

-

Create a national health insurance program.

-

To put in place government sponsored work programs for the unemployed.

-

Give more funds to the arts.

-

Provide amnesty for conscientious objectors to the Vietnam War.

-

Decriminalizing “homosexual conduct.” Ah, that would be an example of a anachronistic policy, but well intended for the time. Pretty woke for someone who still teaches Sunday school.

-

He spoke in favor of Roe v. Wade.

-

And was against mandatory prayer in schools.

As almost an afterthought, he was decidedly dovish on foreign policy, but it wasn’t necessarily central to his campaign persona. Over time, Carter’s foreign policy work would come to define him in both positive and negative ways. Something we’ll spend a great deal of time talking about.

The central Book Love resource for these episodes, by the way, is titled The Outlier. It’s a comprehensive retrospective of Carter’s life and years in office written by Kai Bird, and I can’t recommend it highly enough. In the book, Bird notes that no one was really sure what to make of Carter’s candidacy. For example, Washington reporter Kandy Stroud wrote this of Carter:

“Carter is not just complex, he is contradictory. His paradoxes are multiple. He is at once vain and humble, sensitive and ruthless, softer-hearted and tough, conservative and liberal, country boy with city wisdom, spiritual and pragmatic, loving and cold.”

After spending so much time with Carter, it’s amazing how much this sentiment stands the test of time. Perhaps the only thing more complex and contradictory than Carter himself was the time in which he ran for office and presided over the nation.

The 1970s were bursting at the seams in all corners of the country. The post Vietnam era found a generation of Baby Boomers finally coming of age in a turbulent economy and fractured political environment. Richard Nixon had destroyed trust in the Oval Office, and his VP successor Ford didn’t do much to restore it when his first act was to pardon his former boss. The economy was failing for the first time in earnest since the post war boom and racial tensions continued to seethe, with the Civil Rights movement becoming increasingly factionalized.

This is where many of the comparisons to the present day come into focus. Here are some comparisons from the Brookings Institute, to put things in perspective.

“Elevated inflation and weak growth. The global economy has been emerging from the pandemic-related global recession of 2020, just as it did during the stagflationary period after the global recession in 1975.”

“Supply shocks after prolonged monetary policy accommodation. Supply disruptions driven by the pandemic and the recent supply shock dealt to global energy and food prices by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine resemble the oil shocks in 1973 and 1979-80. Increases in energy prices in the 1970s and during the period 2020-22 have constituted the largest changes in prices of the past 50 years. Then and now, monetary policy generally was highly accommodative in the run-up to these shocks, with interest rates negative in real terms for several years.”

“Significant vulnerabilities in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). In the 1970s and early 1980s, as now, high debt, elevated inflation, and weak fiscal positions made EMDEs vulnerable to tightening financial conditions. The stagflation of the 1970s coincided with the first global wave of debt accumulation in the past half-century.”

Coming into the 1970s, it’s important to remember that the Democratic Party was pretty much in disarray. Memories of the disastrous ‘68 convention still remained and the days of Camelot had pretty much evaporated. Senator Ted Kennedy was probably still the biggest star of the party, but he wasn’t yet of a mind to stake his claim, as the murder of both his brothers still haunted the Kennedy family.

So, the Democrats in contention for the White House to run against Gerald Ford were kind of a motley bunch. Aside from Carter, who had announced his intentions early, the leading contenders were Jerry Brown of California, George Wallace of Alabama, Frank Church of Idaho and Mo Udall of Arizona.

Due to the timing of the primaries, Mississippi was one of the first caucuses held, and Wallace crushed it. Even still, Carter had a relatively strong showing given his southern heritage. The only other notable primary was Massachusetts, which spread pretty evenly among the leading candidates. While Brown and Udall had positive showings out west, Carter pretty much dominated the field and ran the table with an overwhelming delegate count of 2,239. Mo Udall actually came in second with a paltry 330 delegates.

And so, this enigma from Georgia was selected to run against a president who could barely muster the energy to even show that he wanted to keep the job. Even still, Carter’s election was far from a lock.

As much as there were social and economic issues to contend with, it’s important to remember that we were still in the throes of the Cold War during this period. One of the questions that followed the former Georgia governor around was whether he could competently grasp the pressing foreign policy issues of the day.

During the presidential debate, President Ford offered an opening that the media would pounce on. As would Carter.

“There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford administration.”

President Gerald Ford during the presidential debate

Ford had intended to support the people of Eastern Europe and their quest for sovereignty, but instead bungled his response and made it look like he was unaware that the Soviet Union literally controlled the entire region. In an instant, it seemed like the Georgian was amazingly on equal footing with the president where our biggest foreign adversary was concerned.

A begrudging Washington Democratic establishment, along with artists and musicians from Willy Nelson, Hunter Thompson and Bob Dylan, were suddenly on board the Carter train. Many with some amusement, others with great caution. This was their candidate, and as the weeks wore on, the American people warmed to the idea of this soft spoken southern boy becoming president. In the end, it was an extremely tight race, with Carter winning 297 delegates to become the President Elect of the United States of America.

As Kai writes:

“He had come from nowhere and triumphed. Just ten years earlier, he had been knocking on doors, asking people to accept Christ. And now he was the president-elect who owed the establishment nothing.”

In the next episode, we’ll walk carefully through the first half of the Carter presidency. What we’ll find is an astounding record of achievement, along with the seeds of his ultimate downfall.

Here endeth Part One.

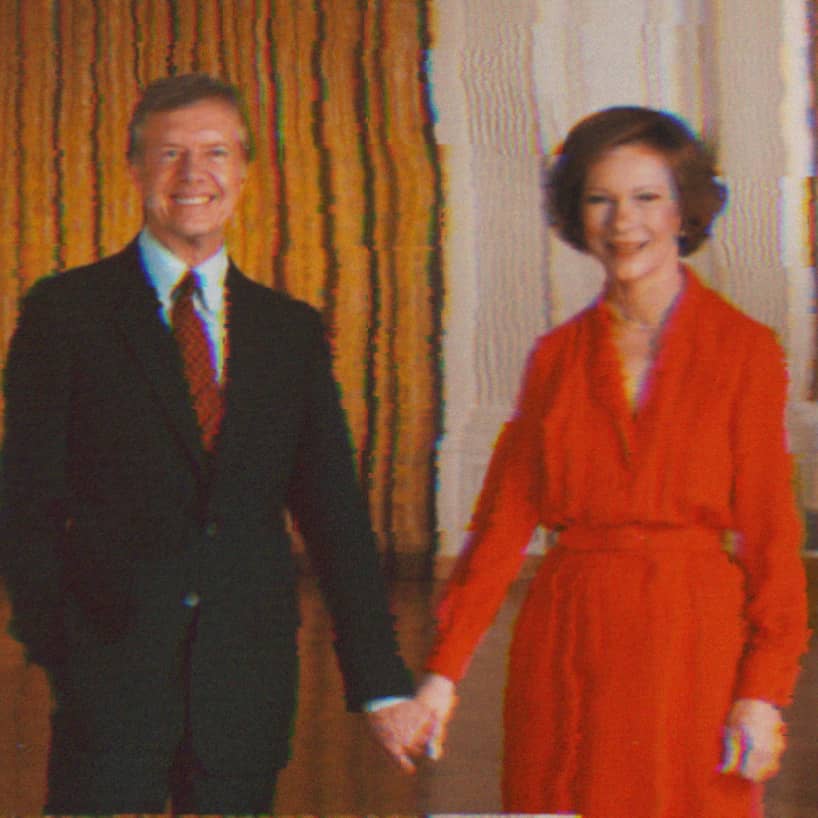

Image Description: Photographic portrait of Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter holding hands in the White House

Image Description: Photographic portrait of Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter holding hands in the White House

Part Two: Carter on the World Stage.

Chapter Three

A President assembles his team.

In August of 1974, President Richard Milhous Nixon resigned from the presidency. By December, former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter announced a longshot bid for the White House. Against the backdrop of a scandalized presidency, 7.5% unemployment and 11.7% inflation, Jimmy Carter campaigned from coast to coast throughout 1975 determined to build support for his campaign one vote at a time. Despite being seen as a Washington outsider, Carter had been cultivating some critical relationships as governor and then presidential candidate.

The outsider image was part authentic and part deliberate. Jimmy Carter was never going to be accepted by the D.C. elite, especially in his own party. But he was also keen to separate himself from an increasingly toxic political environment created by Nixon. By the time of his announcement, everyone was pretty much done with Nixon, including his own party. So the idea of being an outsider worked to Carter’s advantage. But, as I said, he wasn’t without some powerful friends.

One such friend was David Rockefeller, heir to the Rockefeller family fortune forged in oil, railroads and banking. Throughout most of his life, David Rockefeller carefully curated a philanthropic personal narrative, pouring money across the spectrum into foundations and efforts that live on to this day. But in 1973, he founded an organization called the Trilateral Commission, which has been the subject of conspiracy fodder since its inception. Not without reason, mind you.

The Trilateral Commission was conceived as a nongovernmental organization, or NGO, that gathered prominent citizens in America, Europe and Japan to work through pressing trade and economic issues that could serve as a template for international negotiations. As we’ll learn later in our story, some of the members of the commission, especially on the American side, would have a significant hand in guiding American foreign policy, often to the benefit of large financial institutions. Not the least of which was Chase Bank, of which Rockefeller was President. More on that later.

For now, what’s important about the timing of the Trilateral founding was that one of its charter members in 1973 was indeed Jimmy Carter. As Bird notes in The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter, “The Trilateral Commission gave the Georgia governor some foreign policy chops. But, more importantly, he was introduced to Zbigniew Brzezinski and Cyrus Vance, two rising stars of the American foreign policy establishment.”

Both men would wind up in Carter’s cabinet and find themselves in the center of historic events that will eventually come to pass in our tale.

Conspiracists like to paint Carter as a not-so-innocent member of the commission. Perhaps this can be debated. For his part, Rockefeller downplays the significance of Carter’s brief tenure in his memoirs:

“The inclusion among that first group of an obscure Democratic governor of Georgia — James Earl Carter — had an unintended consequence. A week after Trilateral’s first executive committee meeting in Washington in December 1975, Governor Carter announced that he would seek the Democratic nomination for president of the United States.”

Throughout his memoirs, Rockefeller treats Carter as somewhat inconsequential in the history of the commission, though he notes with some optimism that:

“Carter’s campaign was subtly anti-Washington and anti-establishment, and he pledged to bring both new faces and new ideas into government. There was a good deal of surprise, then, when he chose fifteen members of Trilateral, many of whom had served in previous administrations.”

In fact, Carter the anti-politician who famously loathed politicking, made several appointments meant to appease establishment players, though it would never fully ingratiate him in the Beltway. But, it’s important to disabuse this idea that the Carter White House was nothing more than a collection of country bumpkins. While his closest aides and allies were certainly part of his inner Georgian circle, Carter would take great pains to build coalitions, from Ted Kennedy and Thomas “Tip” O’Neill in the liberal wing along with deeply entrenched foreign policy thinkers from Trilateral, to selecting Walter Mondale as his running mate, a rising star within the Democratic Party.

A Strong Hand

Apart from a carefully cultivated team that combined establishment players and Georgia loyalists, newly elected Jimmy Carter had as favorable of a Congressional support system as any incoming president could hope for. Again, Bird:

“On paper, this Democratic president seemed to hold a strong hand on Capitol Hill. Democrats controlled the House, with 292 votes to only 143 Republicans; Senate Democrats possessed a filibuster-proof majority of 62 senators to only 38 Republicans. But the Democratic majority was itself split between liberals and conservatives, the latter invariably from the old Confederacy.”

Early on, Carter made a decision to involve Vice President Mondale in all key decisions, an innovation that we take for granted in this time. After much deliberation, he appointed Brzezinski, known as “Zbig,” as National Security Advisor and Cy Vance as Secretary of State. There was a question as to whether the roles might be reversed, but Zbig was a polarizing figure both in the White House and on Capitol Hill, so Carter thought better of putting him in the more prominent role. Zbig was of Polish descent and carried with him a deep resentment toward the Soviet Union. He viewed nearly every foreign policy decision through this lens, which could serve as an asset at times, but more often a liability. Thus, most consider the casting of their roles a wise choice by Carter.

He even contemplated replacing the CIA Director with two deep establishment liberals, Ted Sorenson, JFK’s speechwriter, and Bill Moyers, the noted journalist. Both were curious choices for this particular role, but it spoke to Carter’s desire to make good with the New England Democrats. Ultimately, he would select an old Navy buddy named Stan Turner to head the agency. Carter had a mind to actually retain the current director, as he was thought to be a competent chief, and Carter would muse after his presidency whether it was a mistake to replace him.

Replace who?

Oh, George H.W. Bush.

Oh. That’s who.

One small anecdote that speaks to Carter’s respect for tradition was a decorating note. Upon arriving in the Oval Office, he noticed that the President's desk was different from the one President Kennedy used. In fact, he was right. So, his first official act as president was to requisition the Resolute Desk from storage and return it to the Oval Office, where it remains to this day.

Carter tapped a former volunteer turned close associate, Jody Powell, to be his press secretary. Together, with Hamilton Jordan (pronounced Jerden), they were considered the new faces of the White House, which irked several of the media luminaries around D.C. who were unsure what to make of these fresh faced southern boys in blue jeans. Nevertheless, Powell and Jordan, Zbig and Vance, and Carter and Mondale set out to make history and restore faith in the White House.

Oh, and I should mention that there was one more unofficial official who would become a permanent fixture in the White House and at the president’s side. As Carter’s Chief Domestic Policy Advisor, lifelong ally and future biographer once remarked, “The Carters don’t have friends. They have each other.”

Rosalynn Carter cut a poised, stable and earnest presence much like her husband. No one questioned her position in the administration or as her husband’s confidante. She was anything but a yes woman and much more than just a sounding board. Rosalynn Carter was an advocate with a voice, particularly surrounding women’s issues. As Bird writes:

“As a guest on Meet the Press and other television shows, Rosalynn projected a polite, soft-spoken image. But her words were wholly feminist in substance.”

With the team in place, a firm policy agenda and a Democratic majority in Congress, all that was left was to govern.

Chapter Four

It was a very good year.

It’s amazing the things that we remember as a people. The things that stick out in our minds. Read my lips. Tear down that wall. Dukakis’s helmet. You’re no Jack Kennedy. Howard Dean’s scream. Mission accomplished. Grab her by the…

Okay, okay. Point being, sometimes the strangest, most unintentional thing leaves a lasting impression. For better or worse.

Here’s Bird:

“Carter addressed the nation for the first time since his inauguration on February 2, 1977, in a televised speech focused on the need to conserve energy. Carter was wearing a beige wool cardigan. Rosalynn tried to persuade him to ditch the cardigan for a blue blazer, but Carter consciously chose to appear less presidential.”

For all the advice he solicited and took from Rosalynn, perhaps he should have heard her out on the cardigan issue. That said, initially, this was received well by the nation and the media. It’s interesting to note that his approval rating in the first six months was 75%. But Republicans would relentlessly trot out the image of Carter in a cardigan for years to come.

Nevertheless, the Carter team went to work on Capitol Hill to try and log an early win. Given it was his first major pronouncement, Carter had a lot riding on an energy bill. From a legislative and allegorical perspective, it’s a great place to start, because it truly captures the complicated nature of energy policy, the legislative process, special interests and Carter himself.

It took months to wrestle an expansive, but muddled bill through Congress. In October of 1978, Carter got his energy bill. The bill created the Department of Energy and provided incentives for domestic energy production, with a particular emphasis on coal. This reflected the nation’s ongoing desire to break from the dependence on foreign energy sources, which was heightened due to the first Arab nation supply shock earlier in the decade. Because coal was still so cheap to produce relative to natural gas—hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” didn’t take off until the early 2000s—it led to a spike in coal and domestic oil production. That’s something that’s largely lost in the discussion from the Carter years.

The balance of the measures in the bill were designed to build a renewable energy infrastructure and encourage large scale conservation. It gave incentives to utilities to conserve energy, required efficiency standards for home appliances, penalized the automotive industry for emissions and provided seed funding for wind and solar to get off the ground.

It was classic Carter. Part ideological, mostly practical. And, without much thought about the impact it would have on the larger economy, so long as it didn’t expand the federal deficit. As Bird writes:

“Carter generally believed in market-driven solutions. He stubbornly resisted pressures from Senator Kennedy and other liberals to consider imposing price controls on oil and gas. His policies pushed oil prices higher, which in turn promoted higher domestic oil production, and that eventually resulted in a decline in oil imports.”

As much as the energy bill was a mixed bag, up until this point, the U.S. didn’t have much of a policy to speak of. In hindsight, the upside was the investment in a renewable future that would slowly persist, despite the Reagan administration’s reversal just a few short years later. One can only imagine how much further along we would be without the interruption of subsequent administration policies.

On the other hand, Carter’s belief in the market would allow further shocks down the line without price controls. And yet again, if you’re in the oil and gas industry, you generally have Carter to thank for the decades of growth they experienced, something that is completely lost in retrospect.

One last note on Carter the environmentalist. While he is generally seen as a green president famous for installing solar panels on the roof of the White House and pressing the nation into developing renewable energy sources, these factors were less about environmentalism and more about conservation. Something that completely fits Carter’s frugal persona.

Playing Small Ball

Carter’s ability to wrestle difficult subjects into legislation was quickly earning him a reputation as a technocrat and a wonk. One way to reflect on how the nation viewed their president in the early days is through the lens of pop culture. For example, there’s an infamous episode of Saturday Night Live where John Belushi as Walter Cronkite hosts a call-in show with Dan Akroyd’s Jimmy Carter. Throughout the sketch, Carter fields calls ranging from how to operate a “Marvex 3000” sorting machine at a post office to talking down a 17-year old caller on a bad acid trip.

There are a couple of insights to glean from this impression of Carter at the time. The first was the belief that Carter seemingly knew everything about everything. It was lighthearted and well-meaning at the time, to be sure. But it would also provide a glimpse into another aspect of his personality that would become increasingly detrimental and, over time, stick to the president in a negative way. And that’s myopia. Oftentimes, it seemed as though Carter focused too much on details better left to others. Every briefing that crossed his desk was not only read but contained his notes in the margins, lest anyone think they could get away with a half assed memo.

One of the early stories that came to symbolize Carter’s myopia was a rumor that he personally signed off on every request to use the White House tennis court. Though debunked by the White House Secretary, it was true that requests had to be made in writing because of the sheer number of tennis players in the West Wing. It was just another example of Carter efficiency and attention to detail. Though it wasn’t him signing off on these requests, the mere fact that a form even existed was enough to provide fodder for the White House Press Corp.

It might seem like a bizarre example to include in a series on Carter, but it’s illustrative of his relationship with a Press Corp bound and determined to find fault in the Georgian at the helm. Tennis request forms, solar panels on the roof, a cardigan sweater. These pieces would begin to paint a picture of a man who appeared small in the face of large problems.

Nevertheless, Carter’s first year in office saw the president continue a legislative winning streak if winning is judged by volume and activity.

As Bird notes:

“The administrations’ first six months were not without substantial accomplishments on the domestic ledger. Economic growth for much of 1977 was running at a robust 5.2 percent. Early in May, Congress enacted Carter’s $20.1 billion economic stimulus package, and soon afterward the president won a job bill for poverty-level youth and a one-year extension of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act.”

This was the type of red meat the Democratic Party was hoping for. Domestic initiatives to combat poverty had taken a back seat from the LBJ years, and the Democrats were keen to restore their image as defenders of the poor and working class. So, from this standpoint, it was a solid first six months for the Carter team. In addition to these measures, the administration expanded the number of food stamp recipients and Carter began an all out progressive assault on the judiciary, appointing a record number of women and black judges to the courts.

But not all of Carter’s proposals would age well in progressive circles. For example, it’s largely believed that Ronald Reagan was the great deregulator determined to set the markets free. In reality, Carter was really the one to pull the regulatory threads, as he was a believer in the markets. In June of ‘77, he began the process of deregulating the airline industry, which brought down prices and increased competition in the marketplace for several years. Of course, as we now know, it eventually led to massive consolidation in the industry and would leave the government powerless to intervene during periods of abusive behavior.

Notching Wins Left and Right

So far, so good. The country was generally approving of their strange and calm new president. Carter seemed on top of everything. He was getting along with the Democratic Party enough to wrestle key pieces of domestic legislation through Congress. Inflation had cooled out slightly. Jobs were returning. Poor people were back on the agenda and there wasn’t a whiff of scandal, much to the chagrin of the press. As Bird remarks, “Every reporter in town wanted to emulate Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.”

Carter continued his legislative agenda unabated with the passage of an amendment to the Social Security Act. It was risky, but necessary. Because prior administrations were loath to increase Social Security deductions, they were falling desperately behind inflation, and there was a fear that the funds would eventually run out. Carter’s amendment increased the tax on anyone earning more than $25,000, something Republicans would characterize as the “largest peacetime tax increase in American history.” They weren’t necessarily wrong. But there’s no question that it was essential to protect the fund.

He would also make the difficult decision to cancel a very expensive defense initiative that everyone knew was a bust, but no one previously had the courage to confront. The disastrous B-1 bomber contract. The B-1 program was outdated, and even the military knew the planes were substandard in the modern era. Yet canceling any military program was seen as heresy. Frugal Jimmy Carter had no such qualms, and so he handed the Republicans yet another eventual talking point by doing the right and difficult thing. On the flip side, as there always is with Carter, he stopped short of cutting the military budget and instead increased it by 3%.

Domestic reform continued to roll, but not always in the direction that the liberal wing of the Party favored. For example, he signed a civil service reform bill that reduced protections for workers by implementing merit based rewards. He also failed to veto a tax bill that made its way to the Oval Office for signature despite being furious that it had gotten this far, saying he couldn’t “tolerate a plan that provides huge tax windfalls for millionaires and two bits for the average American.”

He countered with a proposal to increase the capital gains tax, but found little support in either party. Carter believed that tax cuts in any form would ultimately stoke the flames of inflation. Again, he was a balanced budget hawk who believed in austerity. In hindsight, it seemed as though Carter’s instincts were correct, even though we know that inflation reared its ugly head again more due to the oil shock of the coming Iranian Revolution. But in this way, Carter created a narrative that stuck to him rather than the circumstances; and it seemed like he participated in resurfacing inflation rather than quelling it.

Carter used words like “hard choices” and “austerity” exactly at the time the government needed to ironically invest in the economy, not tighten its belt. As Bird notes, “It was not so clear that government deficits were the major cause of inflation in the 1970s. Labor Secretary Ray Marshall pointed out that the fiscal deficit in 1974 was only $5 billion and yet the inflation rate was 9 percent. Two years later, the deficit had spiked to $66 billion and the inflation rate had fallen to only 5 percent.”

These are the types of historical inconsistencies present in Carter that would ultimately lay the foundation for his demise. But in the immediate, it was an astonishing record of legislative victories unrivaled since LBJ.

Governing from the Middle

The one piece of the puzzle that frustrated Carter was his effort to pass the Labor Law Reform Act, which would have aided union recruitment and penalized corporations who attempted to thwart unionization. It was a terrible fight. Corporations enlisted support from Republicans and southern Democrats to block the law in the Senate. After months of trying to revive it, Carter had to finally relent.

Nevertheless…

-

A comprehensive energy plan.

-

Shoring up Social Security.

-

Appointing black and female federal judges.

-

Amnesty for Vietnam-era conscientious objectors.

-

Cancelation of an expensive and unpopular military program.

There wasn’t a lot of sex appeal, to be sure. But it was the hard work of governing that was required to provide stability and accountability in the nation. And, it seemed as though the nation and economy were responding positively to this renewed sense of calm and capability. Unemployment came down by 1.5%, inflation fell to 4% and GDP increased by an eye-popping 5%.

But the seeds of discontent were already in the ground. The media just couldn’t bring itself to be overly positive about this exceedingly banal White House. The New York Times tepidly praised Carter’s nuts-and-bolts approach, but also called his administration “dull, terribly dull,” as if that mattered. Perhaps more troublingly, however, was the cool reaction Carter and his team continued to receive from the liberal wing of the Democratic Party. As Bird writes:

“To the consternation of many liberals, Carter seemed to be governing more as a Teddy Roosevelt Progressive Republican than a Franklin Roosevelt New Deal Democrat… Carter’s instinct in the face of a growing federal budget deficit was to balance the budget, and that inevitably alienated his liberal constituencies.”

There is a good deal of truth to this sentiment, as we’ll cover. The Carter team lived somewhere in the no-man’s land between Keynesian theory and the ideas developing out of the Chicago School of Economics. And, perhaps Carter would have challenged himself to dig deeper on economic policy and do a better job of reading the economic tea leaves, if he didn’t fall so deeply for a mistress that many had warned him about.

Chapter Five

The Lure of the Siren’s Song.

Carter’s foreign policy aspirations were remarkably clear and incredibly lofty for a peanut farmer from the plains who hadn’t served in any federal capacity. Sure, he had ZBig and Vance, along with the support of several Trilateral Commission members. But his appetite for foreign policy exceeded nearly everyone’s expectations. On his list upon taking office was ending apartheid in South Africa, making human rights a condition for U.S. financial and military support, strengthening detente with the Soviets, and truly opening trade relations with China. Oh, and he wanted to bring peace to the Middle East. Just a run of the mill “to-do” list for any new president who had only ever served as a governor.

Before tackling any of these ambitions, however, Carter would get his PhD in foreign affairs with a prickly issue a little closer to home.

The Canal

It was an issue that no one really wanted to touch. Since its construction, the Panama Canal had been a thorny subject. Many consider the deal to forge a pathway through Panama a crowning achievement of Teddy Roosevelt’s administration, though it was mired in controversy from the beginning. Hailed as one of the most important economic and infrastructure achievements of the 20th Century, the Panama Canal paved the way for trade to increase demonstrably in the western hemisphere. Roosevelt pitted Nicaragua against Panama and kept nearly everyone guessing as to where the canal would actually be built. For several reasons, Nicaragua was favored, as it seemed more feasible from a negotiation standpoint. But Panama was by far the more logical route. Ultimately, Roosevelt pulled off what many consider to be a diplomatic coup by signing a deal to construct the canal through Panama. The only problem of historical note is that no one in the Panamanian administration countersigned the treaty. Because it wasn’t really yet a sovereign territory, it technically belonged to Colombia. A bloodless coup, quick change of hands over the isthmus and an executive declaration later, and Roosevelt had his deal.

Over the decades, as one might imagine, this was quite a contentious issue for the Panamanians, who viewed this as a brazen act of imperialism. I thought it worth a quick history review, because it plays into an important part of Carter’s personality and why he fought an uphill battle to essentially give the canal back to the Panamanians.

Carter proposed a treaty that would allow the United States unfettered access to this important trade route, but hand ownership back to Panama. There were many, not exclusively Republicans, who saw this as a sign of weakness. Forget how we got it, it was ours. There was a legitimate concern on all sides that any new treaty with the Panamanian government could be dicey considering its leader, Omar Torrijos, had come to power under a military coup. And you know how we feel about coups that we didn’t start.

Anyway, Carter took a two-step approach to the deal. The first was to sign a treaty that would place the canal itself in a permanent state of neutrality, but allow the United States to intervene militarily in the event of any threat to this status. The second was to gradually sunset U.S. ownership and hand full ownership and operation of the canal over to the Panamanian government by the year 2000. Many Democrats saw this as an unnecessary risk, especially in the first year of Carter’s term, where it seemed like everything else was coming along just fine. Republicans pushed back hard against the treaties by attempting to add poison pill amendments throughout the process. Ironically, one of the staunchest supporters of the treaties came from one of the most conservative voices in Hollywood. John Wayne, whose first wife’s family had close ties to Panama.

After a pitched battle, the Treaties were ultimately ratified, and Carter had his first foreign policy victory. It was important on several levels. First off, it projected an anti-imperialist shift in U.S. policy that stood in stark contrast to the Soviets. Some, however, would view this as U.S. capitulation and weakness, as Republicans both feared and took advantage of. But, it also served notice that this president would be undeterred and push forward with unexpected savvy to right what he personally viewed as a historic wrong. It also helped build credibility in foreign policy circles that the United States had grown more rational in the post-Machiavellian Kissinger days and that it was ready to do business fairly.

The popularity of the deals was certainly relative. Senators in more conservative districts would pay a heavy price, losing their seats in their next elections, in large part because of their support for the treaties. Ultimately, though, Carter would pay the heaviest price indirectly. This deal would be seen as yet another chink in Carter’s armor when it came to projected toughness when it mattered most in the second half of his term.

A Growing Appetite

Carter’s success in navigating contentious canal treaties through the Senate emboldened him. The steady hand and beyond-his-years wisdom of Cyrus Vance and the pugnacious chirping of Brzezinski awakened Carter in a profound way. No matter how many had warned him, the lure of the foreign policy siren song was too tempting to ignore. Like so many U.S. presidents and other world leaders before him, Carter was intoxicated by the prospect of healing international wounds and righting historical wrongs.

Carter would go on to learn the hard way that foreign nations had their own minds and interests. He may have been more of a gentle soul with an empathic view of the world, but he was still the leader of the United States. And the United States had accumulated some baggage over the years.

Jimmy Carter’s appetite for foreign policy was boundless, bordering on arrogant. Many of the issues he tackled were well beyond his control and above the pay grade of those around him. One particular weakness was the lack of a sophisticated intelligence apparatus. The Carter team was too often surprised by popular sentiment in other nations, and instead willing to take the word of their diplomatic counterparts. Sometimes they ignored real, on the ground intel from their own ambassadors. Sometimes, they misjudged the sentiment of the American people with respect to certain issues.

But to Carter, everything was possible if done with love, an open mind and kindness. It was a complete reversal from the Nixon/Kissinger days that preceded them. When Carter surveyed the globe, he saw historic possibilities. Just a few years prior, Henry Kissinger had opened a secret backchannel to China. Now, Deng Xiaoping was signaling a willingness to open relations with the U.S. under Carter. The Shah was still firmly ensconced in Iran and bending to Carter’s admonitions to do better on human rights. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat was open to negotiating with Israel, thus laying the groundwork for the historic Camp David Accords. Fidel Castro was interested in communicating with the new U.S. President, whom he viewed as genuine and authentic. The Soviet Union appeared ready to soften its Cold War stance.

Everything seemed so utterly possible. If only the world would cooperate and everyone would just see things Jimmy Carter’s way.

Here endeth Part Two.

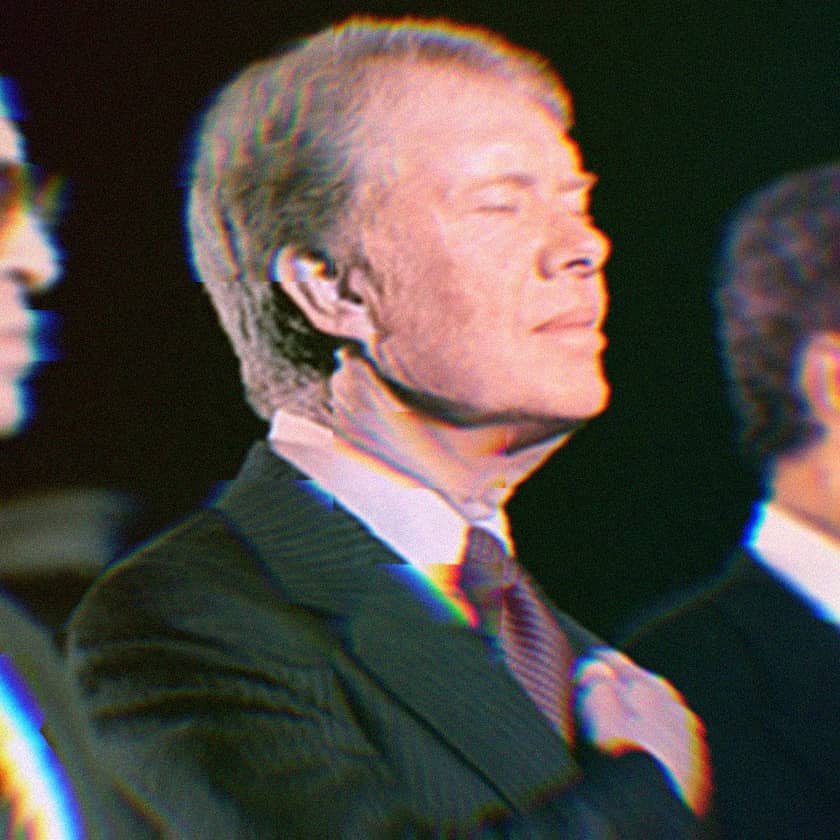

Image Description: Begin, Carter, and Sadat at a ceremony in September, 1978. Carter is in focus and has his hand over his heart with his eyes closed.

Image Description: Begin, Carter, and Sadat at a ceremony in September, 1978. Carter is in focus and has his hand over his heart with his eyes closed.

Part Three: Fallows’ Peripeteia.

Summary: On the heels of multiple domestic and foreign policy successes, the Carter Administration headed into 1979 brimming with hope and optimism. And the American people were mostly supportive of their humble president who helped return some dignity and sanity to the Oval Office. But trouble was brewing from within the Democratic ranks, the global economy and several bad actors abroad that would coalesce seemingly overnight to challenge the president.

A terrible president or a noble man with a lifetime in service? As usual, retrospectives are written along partisan lines. But Jimmy Carter is somewhat of an exception. Carter has been demonized in Republican circles as one of the worst presidents to ever hold office. Nice guy. Lousy leader. Likewise, he’s been shunned by Democrats who refuse to pick up the torch to defend his tenure. Better left in the past. For his part, Jimmy Carter simply didn’t play the game. He spent precious little time defending his presidency or attempting to burnish his image. He didn’t immediately embark upon a revisionist campaign. He simply retreated into private life and used his stature to promote peace, build shelters for the poor and offer his thoughts in numerous books and interviews, but never with the intent to right a historical inaccuracy or rehabilitate his legacy.

Chapter Six

Carter on the World Stage.

With the economy seemingly back on track and a major victory under his belt with the newly minted Panama Canal treaty, everything seemed possible under Carter’s steady hand. Faith was restored in the Oval Office, and the only complaint the press could muster was that the new president was dull. But after the turbulent Sixties and the Nixon years, the country was ready for Carter’s brand of dull.

While there was the normal tension on Carter’s team, most notably between polar opposites Brzezinski and Vance, for the most part the Georgians were making nice and finding their way with the big fish in D.C. Carter’s domestic agenda was on fire, and the Democratic Party was slowly falling in line with the president’s expectations. Midway through his second year in office, with so much left to accomplish on the domestic front, however, Carter seemed preoccupied by the siren song of foreign policy, as many had warned. It’s hard to impress how much of a gamble the Panama Treaty was due to the lack of enthusiasm on both sides of the aisle. So the victory gave Carter a taste of what it’s like to be viewed in positive terms by the rest of the world. Suddenly, everything seemed possible, and the world was in reach.

But trouble was brewing within the Democratic ranks. As Carter peered out over the world, he overlooked a prominent Democrat with his own agenda and his own timetable. Just five years prior to this period, Senator Ted Kennedy had introduced a comprehensive national healthcare bill that would have transformed healthcare in this country in ways that Bernie Sanders would approve. Kennedy’s single payer scheme would have been the death knell for private insurers and set the country on a path that mirrored the rest of the world. But the timing wasn’t right. Now, with a Democratic majority in both houses and a president who seemed capable of negotiating sensitive legislation, Kennedy believed his time had arrived.

So, in July of ‘78, he reintroduced his bill, and it was widely assumed that Carter would carry the water in the White House as he had done with energy. Only, Carter wasn’t interested in doing the bidding of the famous senator, nor was he interested in adding to the federal deficit, saying, “I am not going to destroy my credibility on inflation and budgetary matters.”

While it’s true that it would have expanded the deficit and wreaked havoc in the healthcare marketplace, Kennedy’s legislation probably wouldn’t have had the negative inflationary impact that Carter believed it would. Plus, as we noted in the previous episode, Carter was far more conservative and a supporter of market-based solutions. Rather than punt entirely on an issue that wasn’t all that close to him, Carter negotiated a watered down version of the bill that would preserve a role for private insurers and phase in government options over time.

Kennedy was having none of it. After months of back-and-forth, the two men agreed to meet in the White House to discuss their differences. At the meeting, Kennedy made an impassioned plea to the president to reconsider his stance and Carter agreed to pause and further reflect, so long as they maintained confidentiality between the two of them and worked out their differences behind closed doors. According to the Carter team, the two men shook on this understanding. At which point, Kennedy left the White House and promptly held a press conference lambasting Carter for inaction.

Needless to say, this did not go over well in the Carter camp. From this point forward, all pretense of working together was pretty much thrown out the window. And with that, the stage was set for a battle to come two years later for the presidency itself, and the American people would wind up with nothing on the healthcare front.

Carter’s Moonshot: Peace in the Middle East

Meanwhile, the world beckoned. While Carter continued to battle his own party over domestic priorities, he was privately signaling a much bigger policy play that would alter the course of history. Just a few years prior, Brzezinski drafted a report calling for “a return to the June 1967 borders, full Arab recognition of the Israeli state, and either an independent Palestinian state or a Palestinian entity federated with Jordan.”

Critically, Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat was keen to reclaim territory lost in the ‘67 war to Israel, with an opening for economic and diplomatic recognition of Israel. The opening was too tempting for Carter to ignore, particularly because of the importance this area of the world played in Carter’s faith. Israel was desperate for recognition and cared little about the desert land in Sinai relative to the possibility of normalized trade with an Arab power. Of course, it was understood that peace in the middle east was a moonshot, to put it mildly.

As the historian Lawrence Wright noted, “It was a paradox. Nothing could be a greater gift to Israel than peace, and nothing was more politically dangerous for an American politician trying to achieve it.”

The ‘67 war shocked the world when Israel quickly defeated Egypt, Syria and Jordan to take control of the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza, Golan Heights and the West Bank. The victory threw the Middle East into complete chaos, with the United Nations taking up a resolution calling for the return of the occupied territories. Let’s just say, Israel declined. One of the sticky subjects was the matter of the Palestinian people, who were suddenly living predominantly in the occupied lands but had no recognized government or precise border claims.

On paper and in principle, the Arab Nations called for an independent Palestinian state, but more often than not, even they used the Palestinian people as a pawn in their own games. Even the U.N. Resolution 242 stopped short of calling for a Palestinian state, instead calling for an outline of a roadmap toward one.

Against impossible odds, Carter opened up a dialogue between Israel and Egypt, and he invited Israel’s conservative Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egypt’s President Sadat to Camp David to begin the process.

What’s interesting is that, while Carter was beginning to lay out his plans in the open, Kissinger and Nixon had already opened back channel communications with the Palestinian Liberation Organization, or PLO, as early as 1969. And their work through the mid-1970s had realistically created the groundwork for possible talks in the future.

Camp David

The Camp David Accords would last just shy of two weeks and prove to be the most difficult period of Carter’s young presidency. Sadat and Begin couldn’t be more different and could barely stand to be in the same room, leading Carter to shuffle back and forth between cottages on the grounds. As Kai Bird writes in Outlier, Sadat’s position was straightforward. “Everything was possible,” Sadat said, “if we can get the land occupied since 1967.”

Sadat was in treacherous territory where the other Arab states were concerned. He had already gone it alone, in appearing before the Knesset prior to Camp David. While he was met with somewhat of an open ear, he didn’t have enough to offer the Israelis to make a unilateral deal. But Sadat was indeed a deal-maker and quickly built a close relationship with Carter, whom he viewed as an honest broker. As the leader of Israel’s closest political and economic ally, and with the United Nations behind him, Carter brought more to the table than Sadat could alone.

Begin, on the other hand, proved to be the tougher nut to crack. He and Carter simply didn’t get along. Begin had a tendency to lecture the president. Again, Bird:

“Begin even objected to the use of the term ‘Palestinian people,’ insisting, ‘We are also Palestinians… Begin lectured the president about why the language in UN Resolution 242 could not be part of any Camp David accords — and why he could not abandon any of the Israel settlements in the Sinai… The real obstacle was any deal on the West Bank.”

When Begin rose to power in Israel as the head of the conservative Likud Party, it marked a permanent shift in Israeli politics. Israel was dug in. The hardliners who had fought in ‘48, through multiple Arab-Israeli skirmishes and the 1967 War were determined to not only maintain their territorial gains, but to press further into the Occupied Territories. To them, there was no turning back. On the other side of the equation, there was no credible entity in the eyes of the western world with which to negotiate. As Brzezinski cautioned the President in his briefing, “The PLO is not even a government-in-exile, and they ask for too much from a position of weakness.”

Over the next thirteen days and multiple threats of walkouts, an exhausted Carter finally brought a rough draft of two separate agreements across the finish line. Or so he thought. One of the enduring anecdotes is how Carter finally broke through to Begin, who was literally packing up his cabin with his entourage and heading home without a deal. Here’s Carter in his own words:

“The thirteen days brought a steady, tedious, laborious—most often discouraging—incremental move toward agreement. The hot spots, unfortunately, were those crisis moments when either Begin or Sadat announced that they were leaving. That they were giving up in hopelessness and animosity and disgust. And then I had to induce them to stay for a few more hours, or maybe another day, and give me a chance to find some common ground. On one occasion when Begin was completely committed to leave, I carried some photographs of his grandchildren over. And I had found the name of all eight grandchildren, I had written them on the photograph. Begin looked at them in a perfunctory way, and then he saw the name of his little children, whom he loved, and we started talking about our grandchildren and how the world might affect them adversely if we couldn't find peace. He changed his mind and decided to stay.”

Begin did stay, and Carter pressed Sadat into the same. Together, the three men came up with two separate agreements and side letters, together referred to as “A Framework for Peace in the Middle East.” While it ultimately offered both Israel and Egypt important concessions that Sadat had originally envisioned, it would remain mostly a framework. And it would hardly usher in peace in the Middle East. Too many Arab states were excluded from the discussions, and the U.N. balked at the proposal as well.

Here are the critical parts of the agreement:

-

The status of Jerusalem, negotiated in a side letter at Camp David, would remain murky, with both Palestinians and Israelis claiming it as their capital.

-

Egypt would recognize Israel as a nation and engage in trade.

-

Israel would relinquish to Egypt the Sinai territory taken in the ‘67 War.

-

Recognition of the rights of Palestinian people with a path forward to set up autonomous governments in the West Bank and Gaza.

-

Vague language regarding timetables for Israel’s withdrawal of force from the Occupied Territories.

-

A loose commitment to adhere to the boundaries set by U.N. Resolution 242.

In the end, the Accords were probably more notable for what was excluded. While there was language regarding the rights of Palestinians, it was couched in nebulous terms and relied on Knesset approval, continuing dialogue with the United Nations and a prominent role for Jordan. But Jordan was excluded from the talks, and therefore had little interest in complying with loose agreements and side letters negotiated without its involvement. There was also no specific path forward to resettle the Palestinian refugees who were spread throughout Jordan, Syria and other neighboring countries.

The biggest omission, which would be a source of contention ever since the Accords, was the fate of Israeli settlements in the West Bank, specifically. Every side left with a different impression of the negotiations and the meaning behind the side letters. Here’s Bird:

“Begin did not want a peace with the Palestinians. He wanted a separate peace with Egypt, taking the only major Arab military power off the battlefield. But in the West Bank, he wanted the land. In this sense, Camp David may have been Carter’s greatest diplomatic triumph, but it was Begin’s greatest subterfuge. Within weeks of Camp David, Begin announced that his government intended to build eighteen to twenty new settlements in the West Bank over the next five years. Carter was furious.”

Begin returned home a hero. The land in Sinai was important to Israel for its access to waterways, which Israel received as a result of the agreement anyway. More importantly, it had taken a huge step forward with diplomatic recognition by a key Arab state and open trade agreements that would allow it to boost its economy. But, mostly, it was the vague language regarding Palestinian rights and the status of settlements that made Begin triumphant in the eyes of Israelis. The side letters were ignored completely. Within days of his return to Israel, Begin announced the construction of new settlements and, over the next few years, the Jewish population in the West Bank rose from 5,000 to 24,000. “As Carter feared, the settlements would poison his greatest diplomatic triumph,” noted Bird.

Sadat’s fate was far more bleak. Shunned by his allies and thrown out of the Arab League for going rogue, Sadat became increasingly isolated. Three years after the Accords, and being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize with Begin, Sadat was gunned down at a parade. Armed militants within the government hit Sadat with 37 bullets in retaliation for what they viewed as the ultimate betrayal.

Chapter Seven

Fallows’ Peripeteia.

January, 1979.

Inflation: 9.3%.

Unemployment: 5.9%.

Carter’s approval is 50%.

Carter’s foreign policy team continued to pick up Kissinger’s pieces all over the world. Brzezinski, in particular, was determined to set himself apart from the controversial Kissinger, who frequently undermined him to the press. Early in 1978, Zbig conducted under the radar meetings with Deng Xiaoping and was enthusiastically promoting China throughout the White House upon his return, prompting Carter to accuse him of being seduced. But the breakthrough was real and in short order, the United States and China formally opened diplomatic and trade relations, thus ushering in the modern economic era.

But, for as much as 1979 was brimming with promise, the world was slowly beginning to unravel.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, better known as The Shah of Iran, enjoyed a long dictatorial tenure, during which he sought to make Iran a major economic player on the international stage. He had the support of western allies, in particular, who safeguarded his time as leader. In 1978, however, with unrest among youths growing in the streets, the Shah’s military opened fire on protestors in Tehran. Religious fervor had already captivated many of the youth in Iran’s cities, and the right wing clerics seized upon this horrific event to stoke the flames of unrest. By the end of the year, the Shah’s position and grip on power became untenable and the exiled leader of the religious right, Ruhollah Khomeini, known as the Ayatollah Khomeini, returned triumphantly from exile to take power and turn the government of Iran into an Islamic theocracy.

The Shah’s ouster shocked the world, and unfortunately caught the Carter administration completely off guard. We’ll return to this crucial part of the story shortly, but the important takeaway here is the utter failure of the intelligence community to grasp what was happening on the ground. Carter looked even more out of touch, having recently hosted the Shah in the United States and calling him a trusted friend.

Behind the scenes, ironically, Carter had been the Shah’s harshest critic compared to previous administrations. Because Carter had crafted his foreign policy around a humanitarian-first principle, he admonished the Shah from the start for wielding too heavy of a hand. An important historical note about the Shah’s relationship with the United States is the extremely close relationship between him and the members of the Trilateral Commission, David Rockefeller and Henry Kissinger being chief among them. While Carter turned his attention elsewhere, Rockefeller and Kissinger would begin a covert campaign to protect their interests behind Carter’s back.

Carter’s problems at home and abroad were beginning to mount. Inflation was proving to be a real issue, and the trouble in Iran wasn’t helping matters. Across the globe, the economy was cooling off, and Carter’s insistence on tightening the belt domestically wasn’t helping matters. In just a few months, the administration went from the high of the Camp David accords, domestic legislative successes and the opening of relations with China to playing defense on several fronts. The Washington Press Corps wasn’t helping either. In their relentless pursuit of scandal, they were beginning to tire of the President’s squeaky clean image and started looking for trouble whenever and wherever possible. And, because the good old boys in particular didn’t fit into the Katherine Graham-style Washington mold, they were constantly being picked apart in the gossip and opinion pages. And it was wearing them down.

Between inflation, another gas crisis due to the Iranian Revolution, Zbig and Vance sniping at each other and unemployment beginning to creep, the President’s numbers were flagging. And then, the beginning of the end came in an article penned by a former ally and employee in the White House, who broke everyone’s heart and spirit.

In May of 1979, an article appeared in the Atlantic, titled The Passionless Presidency. It was written by former staffer and speechwriter James Fallows.

Fallows was a young journalist who was wooed by a friend to join Carter’s team. While not his first choice for a career, the upside was undeniable, and so he put his career on hold to join the executive team. Fallows was well liked by everyone, including Carter, which made his critique that much more devastating. In our frenetic 24/7 news cycle today, it’s hard to appreciate how much weight a single article could carry. But it helped cement in the public’s mind what was going on behind the scenes in the White House, and it would haunt the Carter team for the rest of their lives. Fallows believed he was simply doing his job after leaving the White House just a few months earlier. He was a witness. This was a first hand account. And it was his obligation. The piece started off with extremely positive characterizations of Jimmy Carter the man:

“After two and a half years in Carter's service, I fully believe him to be a good man. With his moral virtues and his intellectual skills, he is perhaps as admirable a human being as has ever held the job. He is probably smarter, in the College Board sense, than any other President in this century. He grasps issues quickly. He made me feel confident that, except in economics, he would resolve technical questions lucidly, without distortions imposed by cant or imperfect comprehension.

“In his ability to do justice case by case, he would be the ideal non-lawyer for the Supreme Court; if I had to choose one politician to sit at the Pearly Gates and pass judgment on my soul, Jimmy Carter would be the one.”

The pleasantries end there. For the next several thousand words, Fallows eviscerated the administration. Here are some excerpts, all quotations.

-

Carter and those closest to him took office in profound ignorance of their jobs.

-

The President seemed to foresee neither the temptations nor the demands of foreign policy, nor the ways to prevent them from stealing his concentration away from other pressing business of his office.

-

He did not know how congressmen talked, worked and thought, how to pressure them without being a bully or flatter them without seeming a fool.

-

If there has been little abuse of power, it may be because they have so little sense of what power is and how it might be exercised.

-

I came to think that Carter believes fifty things, but no one thing.

-

He is a smart man, but not an intellectual in the sense of liking the play of ideas, of pushing concepts to their limits to examine their implications.

The piece borders on harsh truths and slight inaccuracies. But it was the first hand nature of it that made it so damning, especially because Fallows left on good terms. And these highlights are just that; a smattering of criticisms among a torrent. In hindsight, if ever there was a turning point in a tragic story, this was it.

Chapter Eight

Mudslide.

June, 1979.

Lest we forget, the nation was still in the midst of the Cold War. The extent of the decline within the Soviet apparatus was still unclear in the west. Though, there was some hope within the Carter administration that relations were beginning to thaw. Most pressing on the diplomatic agenda was to revive the stalled SALT treaty talks with the Soviets. Most within the administration believed that productive talks were within reach, and there seemed to be a greater level of trust in the U.S. without Kissinger at the point person. But there was one major obstacle from within. Zbig.

“Relations between Vance and Brzezinski were obviously getting frayed… [Brzezinski] continued to badger the president to link passage of the SALT treaty with Soviet behavior in Angola, Zaire, Yemen, and eventually Afghanistan,” writes Bird. Undaunted, President Carter met with Soviet Chairman Leonid Brezhnev in Vienna and signed the SALT-II agreement, designed to establish parity between the nations in nuclear delivery systems and limit the number of multiple warhead missiles. The reality was that the treaty did little to slow the arms race, but the Carter team believed it to be an important step in opening dialogue and transparency between the two countries. Unfortunately, the American public saw it differently.

Neither side of the aisle in the U.S. was particularly happy about the negotiations. The right saw Carter as a sellout, and the left saw it as wholly inadequate. Carter’s people still needed to ratify the treaty in Congress, but this wasn’t Panama and Carter was beginning to lose influence within his own party.

July, 1979.

Inflation: 11.3%.

Unemployment: 5.7%.

Carter’s approval is 30%.

Carter was aware that his grip was slowly slipping on important matters. The Fallows’ article had shaken the confidence of his internal team, and Zbig and Vance were increasingly at odds, particularly over the SALT talks. In July, a White House pollster and polarizing figure named Patrick Caddell, whom a Carter associate once referred to as “Rasputin,” planted a bug in Carter’s ear. He suggested a summit with top Democratic leaders and officials from around the country to earnestly diagnose what ailed the nation. The idea was that Carter had taken his eye off the ball pursuing foreign policy and was quickly losing touch with the pulse of the nation.

Many were surprised when Carter took Caddell’s advice and cleared the White House calendar. For several days, he gathered with Democratic leaders and listened intently and genuinely to their criticisms and advice. Those in attendance would later remark, somewhat in awe, at how Carter absorbed criticism and encouraged honest feedback. It was a stunning display of humility and genuine concern for the nation.

Here’s Bird. “After ten days, on July 14, 1979, Carter came down from Catoctin Mountain Park and spent the next day editing the speech that would ultimately become a turning point in his presidency. He spoke for thirty-three minutes.”

The speech has been referred to both as the “malaise” speech and the “crisis of confidence” speech. Either way, the immediate impact of it was palpable, and for a brief moment, the American people were galvanized in support of their president, who was delivering tough love and speaking to them as peers and from the heart.

Carter wrote every word of the speech himself. And it did resonate for a time with average Americans. But the problems he identified, outside of the crisis of confidence, were bigger than a momentary motivational speech. There were gas lines. Inflation was brutal. Jobs were being lost. The economic realities were ever present in the American mind, and they were certainly more important to voters than some conservative regime in Iran or mediocre treaties with the Soviets. People wanted a leader to take hold of domestic affairs and assure them that everything was going to work out. That piece Carter did tap into. And it came from one particular attendee at the summit, who put it bluntly and succinctly to Carter in words that stayed with him. “Mr. President, you are not leading this nation, you’re just managing the government.”

The reason this moment stuck with Carter, and all those in attendance, was because it struck at the heart of the problem with Carter’s style. So, yes. The speech did work for a time, but the harsh economic realities would ultimately prove to be too overwhelming. And, like so many other seemingly insignificant moments—the cardigan sweater, scheduling time for tennis, solar panels on the White House—the speech would eventually be woven into a larger loser narrative that Carter was built for small ball and not up to the moment. In the end, the American people didn’t want to be leveled with, they wanted someone to fix things.