Labor Unions: From Pullman to Kellogg’s. Labor’s Long, Hard Road

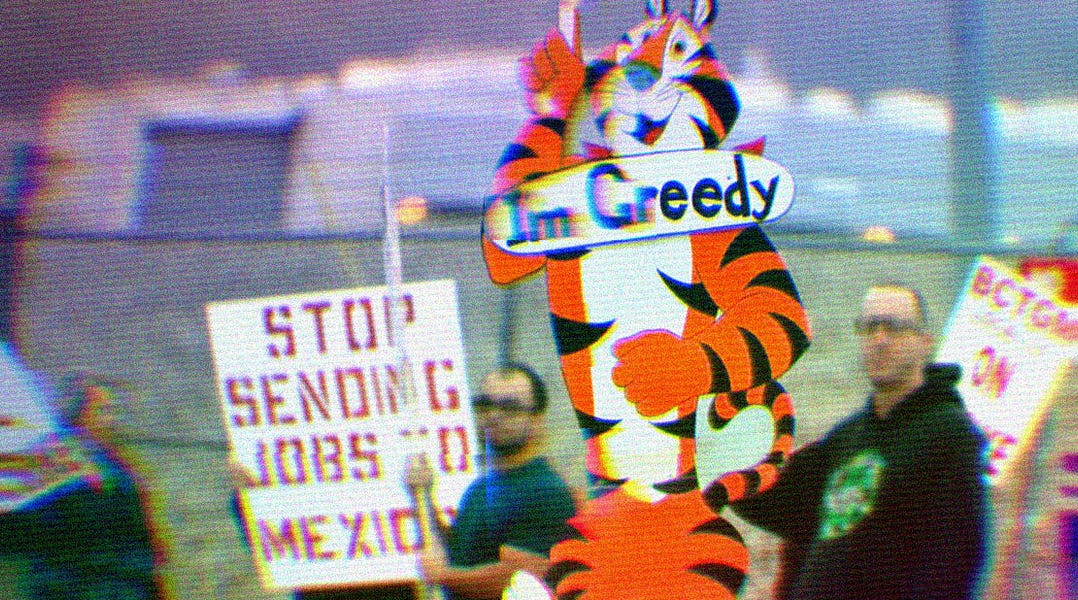

Image Description: Kellogg's strikers holding signs. Main sign in focus is Tony the Tiger, saying "I'm Greedy."

Image Description: Kellogg's strikers holding signs. Main sign in focus is Tony the Tiger, saying "I'm Greedy."

2021. Drivers, mechanics and other staff in Maine have unionized with the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 714. Some 32 transit drivers, mechanics and other staff joined Local 714 and will soon be negotiating their first contract.

In 1953, 29.6% of the American workforce belonged to a union.

2021. Booksellers at Skylight Books in Los Angeles voted to join the Communications Workers of America (CWA). The newly unionized workers seek to have management address a dozen issues, including regular staff meetings, guaranteed raises and more equitable hiring practices. Management immediately granted the union voluntary recognition.

In 1974, 24.8% of the American workforce belonged to a union.

2021. After a strike that lasted six weeks, United Food and Commercial Workers members at Heaven Hill Distillery in Kentucky reached an agreement on a new contract. The new contract preserves affordable healthcare, increases pay, maintains overtime provisions and strengthens retirement security, among other provisions.

In 1983, 20.4% of the American workforce belonged to a union.

2021. Librarians and other workers at Worthington Libraries in Ohio voted 80–10 to form their union with the Ohio Federation of Teachers, an affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers. And writers, producers, fact-checkers, editors, engineers and art directors at The Atlantic overwhelmingly voted to form a union with The NewsGuild of New York.

In 2000, 14.1% of the American workforce belonged to a union.

2021. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan announced that the state will now require contractors and subcontractors to pay prevailing wage on all state construction projects.

In 2020, 10.8% of the American workforce belonged to a union.

2021. Employees at a Buffalo-area Starbucks store have voted to form a union, making it the only one of the nearly 9,000 company-owned stores in the United States to be organized. New York Times reporting.

The Myth of Benevolent Capitalists

Gather round, Unf*ckers. Before we get to all the hootin’ and hollerin’ about “Striketober,” Starbucks and Kellogg’s, I want to take you back in time a bit. Back to the industrial revolution, you know the period that libertarians and Milton Friedman acolytes masturbate to. An economic period built on brutalizing workers and exploiting child labor.

In fact, the 1900 Census showed that 6% of the workforce was composed of child labor because, lesson one, corporations left to their own devices without proper regulations are inherently evil. The U.S. government attempted to reform this practice with a national review board, but it relied on states to implement measures to protect children.

It wasn’t until 1916 that Congress passed the first national reform called the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act, specifically prohibiting child labor. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court ruled this unconstitutional, leaving the practice in place for two more decades proving, lesson two, that old men in robes are the fucking worst and hardly blind to justice. Child labor wouldn’t be officially outlawed until 1938 when the Fair Labor Standards Act, a law almost identical to Keating-Owen, was passed and successfully defended at the Supreme Court.

Three years prior to this, however, something called the Wagner Act was passed and had far reaching consequences for owners and labor. Much of what was contained in this act remains hotly contested even today, or was steadily undone over the next several decades through legislation hostile toward unions. Crafted by Senator Robert Wagner, the Wagner Act was considered the “Magna Carta” of the labor movement. In his book, The State of the Union by Nelson Lichtenstein, the author says Wagner:

“Guaranteed workers the right to select their own union by majority vote, and to strike, boycott and picket. And it enumerated a list of unfair labor practices by employers, including the maintenance of company-dominated unions, the blacklisting of union activists, intimidation and firing of workers who sought to join an independent organization, and the employment of industrial spies.”

Wagner was long overdue. Prior attempts to codify workers’ rights had nearly all ended in disaster. It wasn’t that unions didn’t exist prior to Wagner, but they were largely mistrusted by corporations and politicians who viewed them as collectivist threats. I want to offer two examples from this era, the height of the industrial revolution, that I feel are extremely relevant today because the men in power were considered to be good and benevolent. Andrew Carnegie and George Pullman. The former enjoys several historical rewrites to paint him through his charitable work as one of the most magnanimous Americans who ever lived.

Carnegie was a titan. One of the wealthiest men who ever lived. He’s known today as the great philanthropist of the ages, but the story of his accumulation of wealth is the same as all other preposterously wealthy individuals. Built on the back of and at the expense of labor. At the height of his power in the late 1800s, Carnegie controlled a vast steel empire that he would ultimately sell to J.P. Morgan, who consolidated steel holdings in a trust known as U.S. Steel.

While it’s true that Carnegie would devote his life after selling his interests to philanthropy and education, there’s one event that marred his reputation during his lifetime. The Homestead Strike. Carnegie’s workers were part of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers and were working under an agreement in the 1880s that was set to expire. Rather than renegotiate in good faith, the company worked actively against the union to try and break it up instead. Over a period of a couple of years, tensions finally boiled over, and the workers went on strike. Because Carnegie had until this point paid lip service to the working man, he was in a bind. Rather than lose face, he took off on a long vacation to Scotland and left his anti-union chief, a dude named Frick, in charge of handling the strike. During this time, all hell broke loose.

Carnegie’s corporation compelled law enforcement to compel the workers to end the strike and hired an outside agency called the Pinkertons, a private contracting security firm that essentially employed armed goons to do the dirty work the law wouldn’t do. After initially rebuffing the Pinkertons, the employees were ultimately overwhelmed, and the strike ended in brutal fashion with several dead and the union defeated.

Then there’s good old George Pullman, the railcar tycoon who went so far as to build an entire town for his employees. Pullman was a true innovator and man of the people, until he wasn’t. Pullman owned all the real estate in his Illinois town where his employees worked and gave them housing, with the rent being deducted from their paychecks. Everything was rather fine and dandy, and Pullman was the darling of capitalists far and wide for creating a benevolent working utopia.

But when a recession hit and orders for his Pullman railcars slowed down, Pullman instituted wage cuts across the board for his workers. The only problem is that Pullman executives saw no such pay cut and the workers saw no reductions in their rent. This left most of the employees in a dire situation that pushed them to the brink and forced them to strike. Like Carnegie, Pullman had his limits, only he didn’t flee the country. But he did hide from the press for a while. And while he hid, the Pullman strike turned into a national railway strike in solidarity and it nearly brought the nation to its knees.

Pullman enlisted the support of the Cleveland administration, whose attorneys coyly argued that the rail strike was prohibiting mail from being delivered on time and was therefore a national emergency. Here again, the government sent in federal troops to beat back the strikers. The strike itself was organized by some of the most prominent figures in U.S. history and important figures for years to come in the fight for social justice. Samuel Gompers, who actually punked out like a bitch at the last minute, Eugene Debs, arguably the most famous socialist in U.S. history and Clarence Darrow, famed liberal attorney and activist. In the end, the workers lost. Debs was jailed. Strikers were beaten, and the government proved that it would always intervene on the side of big business.

As Philip Dray writes in There is Power in a Union:

“The movement learned decisively that it had no friends in Washington, and that the federal government would not hesitate to send soldiers to confront workers pressing legitimate grievances. Most disturbing was the government’s use of an antitrust law to halt union organizing and even gag communication from a union’s leaders to its members, a throwback to the supposedly discarded notion that routine labor union activity represented a “combination” or “conspiracy” dangerous to society.”

But, hey. At least the Pullman strike made Congress feel guilty enough to give us Labor Day. Sorry about all of the corruption, murder and suppression. Here. Have a day! Someday, you’ll be able to get up to a 50% discount on a mattress and bed frame on this day as we force all retail operations to open in celebration of consumption.

I wanted to start with this because, as we jump forward in our little tale today, it’s clear that we’ve found ourselves right back at the beginning of the struggle with powerful forces working against the working class, the working class working against itself and government and elites aligned with the billionaire class, still believing in the myth of benevolent capitalism.

Unions Through the Years

The 1920s and 30s

So in the beginning of the 20th Century, labor was still in a precarious position relative to the growth of the U.S. economy. Labor unions were a thing, but they had yet to gain serious traction and were more often than not brutally suppressed by giant corporations who, along with Wall Street, posted historic gains. Of course, what goes up…

So on the theme of familiar refrains, as the industrial era matured and we hit the roaring 20s, things were pretty rosy for big business and Wall Street. As Lichtenstein put it, “In the decade that ended with the crash, output per worker in manufacturing leaped upward by a remarkable 43 percent, while wages barely held their own. Meanwhile, the incomes of the very rich—the top 1 percent of the population—rose from 12 to 19 percent of that generated by the entire nation.”

As the nation, and in fact the world collapsed into the Great Depression, it became painfully evident that some reform was required in the system. To put it mildly. The complete absence of worker protections was one thing when there was work. But when the country went belly up, it exposed every crack, every weakness in the system. For a brief period of time, there was actually alignment in this belief from the elites down to the gutter, but not always for the same reasons.

It should be recognized that only white males had agency in the fight for union rights until now. With southern blacks living under horrid Jim Crow conditions, northern communities shunning black migration north and women completely disenfranchised in the industrial sector, the movement struggled to gain in numbers and consolidate power. Ironically, it was the Communists who viewed black membership as vital to the success of the labor movement.

In fact, one of the Communist slogans of the 30s was “Negro and White: Unite and Fight.” This was an enormous statement at the time because, until this point, segregation was the way of the American world in every way possible. There were black unions and robust membership in the south, but the struggle for workers’ rights was seen as a uniquely white struggle. But the communists understood that, as Lichtenstein writes, “Equality between African Americans and whites would not be limited to the work site or to the union membership roster. It must prevail at every level of existence: in the courts and at the ballot box, certainly, but also in the realm of social life: the neighborhoods, schools, summer camps, dance halls and marriage beds.”

This was a completely radical notion that changed the perception of some union members and leaders such as Debs, though others like Gompers were unmoved. But the idea was introduced, and it was out there. Change in one area of society couldn’t possibly account for what was truly required to improve society. America and capitalism at the time looked as though they had failed. And here, amidst the most radical element feared by most Americans, was a vision of equality that held great appeal to black people and women and white men who suddenly found themselves on the losing end of the capitalist bargain. Unions weren’t solving issues of gender or race. Unions were about the class struggle.

There was another element that is strange in retrospect, in how the Depression turned Americans against the elite power structure and created an authentic connection between the struggles of the working class and the promise of America. It suddenly became patriotic to be on the side of the working class. Again, Lichtenstein:

“The depression-era labor movement deployed huge American flags in all its struggles, even those led by avowed leftists. The national banner symbolized the power of a newly assertive federal government and the kind of ethnically diverse Americanism the new unionism and the New Deal sought to build. Waving the Stars and Stripes, American unionists announced that they too were part of a patriotic tradition that was expansive enough to enfold a new industrial democracy.”

One of the most game changing strikes in history was at General Motors, a behemoth by any standards, and incredibly hostile to workers who were spread out across the country in various plants. Organizing on this scale against a formidable giant was no small task and carried great risk of scabs and outside agitation by management. So the employees organized a physical occupation. As Lichtenstein explains, “During the course of the six-week factory occupation, Flint sit-downers held frequent meetings, conducted classes in labor history, put on plays, prepared their meals, and scrupulously avoided damage to company property or products. They drew upon nearly a decade of labor-left political and social activism to construct a counter hegemonic union culture with which to challenge GM’s corporate worldview.” And thus the UAW was born.

The 1940s and 50s

The story of union organizing in the United States is a story of workers. The story of union busting is equal parts race, gender and class. Nowhere is this tension more apparent than the 1940s and 50s when union membership reached a peak, then began its long descent to where we are today, brought down by a combination of racism, sexism, classism, red scare fear mongering and ultimately, free market ideologues hell bent on destroying the lower classes in America.

This brief period in the 40s and 50s, as the country pulled out of the Great Depression with New Deal reforms strengthening the foundation of the working class, was huge for labor because the economy had finally caught up with the hard fought New Deal protections and gains for workers. World War II had enormous social and economic impacts on the U.S., and the postwar boom represented the height of union membership and activity.

By now, southern blacks had migrated to northern urban environments and were occupying important roles in factories and plants across America. Women, who were called upon to enter the labor force, suddenly had a seat at the table, if only in a limited capacity. The general acceptance of union labor was wholly new and carried great potential for labor, but there was trouble brewing on the horizon as the power structure had also regained its footing in the post-war economic boom and the powerful elites were determined to recapture their supremacy at the expense of the working class.

In terms of legislation, this didn’t take long at all. Immediately after World War II, the Republicans had taken over and set about dismantling New Deal era reforms as quickly as possible. Though it would take the next three and half decades between the war and the Reagan era war on labor to bring to fruition, the opening legislative shot came in the form of the Taft-Hartley law. Originally touted as a way to purge communists from union rolls, which it did, it had even more deleterious provisions, such as the right to enact what are called “right-to-work” statutes that were determined on a state-by-state basis.

These statutes were intended to divide the union membership at the state level and put more power into the hands of corporations. They put corporations back on even footing with unions and employees and allowed companies to skirt laws against intimidation tactics under the guise of free speech.

-

By shifting the onus to individual states, anti-union powers were able to separate the centers of power in large unions.

-

By cloaking intimidation tactics in free speech language, it allowed corporations to once again engage in fear mongering over employment stability.

-

And by demonizing the unifying philosophy of socialism and communism, it was able to create hierarchies and distrust within membership.

Dray concedes additional factors on top of the structural issues created by Taft-Hartley.

“The loss in the perceived importance of unions was due in part to worker complacency made possible by a strong postwar economy. Technology had also played a role, diminishing the number of industrial jobs around which labor organizing was traditionally centered, and creating new white-collar occupations more associated with management than with labor. Taft-Hartley had excluded foremen and supervisors from labor-law coverage, which made workplace unity more difficult because fewer new jobs were blue-collar in character.”

The bottom line is that all of the union mojo gained throughout the difficult years of the Great Depression and the Second World War soon dissipated now that the country had recovered.

The 1960s and 70s

Unfortunately, our story doesn’t get much better from here. Ironically, the success of the Civil Rights movement had the unintended effect of further fracturing the delicate relationship between black and white workers. Essentially, there was only so much energy and bandwidth that could be deployed, and LBJ’s Great Society years put some crucial building blocks to equality on the table.

Prior to the Voting Rights Act, Equal Employment Opportunity Act and the Fair Housing Act, along with safety nets such as Medicare, unions were the only thing that resembled something close to equity in the black community.

Black leaders had their eyes on the prize and union leadership was all too anxious to revert back to their segregated ways. So, as usual, black Americans were filling one pocket with overdue justice measures while white leaders reached their hands into their other pockets. As the Civil Rights movement raged on, blacks were achieving huge victories, only to see their numbers begin to dwindle in the ranks of the unions. First through separation of management from workers, another important part of Taft-Hartley, then through reduced recruitment and outright bullying.

Essentially, the economy was hot, and white workers began to reassert themselves against black workers. All the while corporate and Washington elites were reasserting themselves against the entire working class. Bit by bit, inch by inch, unions were unraveling.

-

Separate them federally, and make them battle at the state level.

-

Separate management from workers.

-

Separate blacks from whites.

-

Then, turn them all against one another through propaganda made worse by endemic corruption among union leadership.

As Kurt Andersen writes in his incredible book Evil Geniuses; The Unmaking of America:

“Back in the day, unions had been an essential countervailing force to business, but now—having won forty-hour weeks, good healthcare, good pensions, auto worker salaries of $75,000 (in 2020), OSHA, the EEOC—organized labor was victorious, powerful, the Establishment. These powerful institutions, the former machinist Irving Kristol astutely wrote at the beginning of 1970, just before publicly moving full right, were, inexorably being drained of meaning, and therefore of legitimacy.”

Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller’s book, titled Narrative Economics, examines the power of story in driving economic events. In it, he speaks to a prevailing narrative in the 1970s, which is arguably the final turning point in America in anti-union sentiment after decades of falling in and out of favor. The concept that came to the surface was something called the “wage-price” spiral. Here’s Shiller’s explanation:

“The wage-price spiral narrative described a labor movement, led by strong labor unions, demanding higher wages for themselves, which management accommodates without losing profits by pushing up the prices of final goods sold to consumers. Labor then uses the higher prices to justify even higher wage demands, and the process repeats itself again and again, leading to out-of-control inflation.”

We’ve covered in previous episodes how the stagflation shock of the mid 1970s resulted from the OPEC oil shock, convulsions in global markets from the U.S. repeal of the Gold Standard, two revolutions in Iran and Fed intervention policies. But these factors would blow back on the Carter administration and pave the way for Reaganomics. It would also contribute to great antipathy toward unions who were seen as greedy, corrupt and the cause for the wage-price spiral.

Uncle dickfart was right there to fan the fucking flames, claiming that all of the best gains in human history happened during the industrial revolution before workers came along to ruin everything.

#FMF

That’s because you had child labor and abused workers. Oh, and during this time period that you love so much you fucking mealymouthed cretin, there was a recession in 1847, 1853, 1857, 1860, 1865, 1869, 1873, 1882, 1887, 1890, 1893 and 1896! That’s 12 recessions in 50 years, and that doesn’t even take into account the number of industrial deaths in factories, you fucking shill.

But the damage was done. Union support dropped precipitously within one generation. Mind you, there were plenty of self-inflicted wounds along the way, not the least of which was endemic corruption at the highest levels, personified by the likes of Jimmy Hoffa. As Philip Dray notes:

“The negative image that had long haunted labor was that it was radical or socialistic; now, ironically, even as the movement had struggled to defeat such impression by publicly denuding itself of Communist influence, and striking at its manifestations elsewhere, it had been blindsided by attacks that linked it with something tawdrier, a sin even more offensive.”

Corruption, as Dray indicates, was more insidious than even Communism. Socialism, Communism. These were external threats. But corruption? That was internal. It was a disease.

Kurt Andersen marks the 1970 Hard Hat Riot in New York City as the great cultural and psychic shift in antagonism between white working class union members and liberal elites, a coalition that was once unified in protecting the rights of workers. In his book Evil Geniuses, Andersen relates the account of union construction workers descending on a group protesting the student murders at Kent State. The construction workers, many of whom were wearing hard hats—hence the name—brutalized the young protestors, chanting “All the way, U.S.A.”

Somehow, the idea of protest, even at something as horrific as the Kent State massacre, became synonymous with anti-American sentiment. Management was able to wrap the hard hat in a flag and paint defenders of free speech and peace as pinko commies and leftists. Here’s Andersen:

“Beginning right then, in fact, the suspicion and contempt between less-educated white people and the liberal white bourgeoisie was what the American class struggle was most visibly and consciously about. And it would define our politics as the economy was reshaped to do better than ever for yuppies and worse and worse for the proles, regardless of their ideologies and cultural tastes.”

H.R. 842 - PRO ACT

We’ve covered a bunch about Reagan in our time together, although we didn’t specifically address his hostility toward any union that didn’t represent law enforcement. These types of service unions—anything involving force and law and order—is completely on brand for the Republican Party and continues to be so to this day. But Reagan would also chip away at the structure and foundation of trade unions and other service unions, a practice furthered by every president since that time. Until today, amazingly.

In rhetoric, at least, the thing about Biden is that he’s the most vocally supportive of all types of unions of any president in my lifetime, certainly. Whether he ultimately puts energy and weight behind labor remains to be seen and, as we’ve discussed, his time is almost up because the midterms are likely to be a bloodbath. But he did come out, again rhetorically, in support of the Kellogg’s strike and is generally sympathetic in tone to recent efforts on the part of unions. We’ll see.

As of right now, the Senate has a bill in front of it that has already been passed by the House called H.R. 842: Protecting the Right to Organize Act of 2021. It passed 225 to 206 and is designed to reduce intimidation tactics on part of employers, take immigration status threats away, unions could supersede “right to work” laws in individual states and end the practice of replacing strikers with permanent workers.

Of course, Biden’s not really talking about this bill very much. And the Senate is too afraid to get rid of the filibuster, so this bill probably isn’t going to see the light of day unless I’m really missing the mark here. I just don’t see it happening. That’s why so much of the rhetoric is already falling so flat. H.R. 1 for the People. Vital for our democracy. Not hearing much about it. H.R. 842 protecting the right to organize. Probably going to die. Giving up on the social infrastructure elements of Build Back Better so we can just print enough money to repave every road and line Time Magazine’s fucking Person of the Year Elon Musk’s pockets even more by building out his charging infrastructure across the country. Sure, why the fuck not?

I don’t want to just rant about this, though. So I thought it would be interesting to do something a little different to really contextualize a real life labor struggle by examining the language of Wall Street. Then I’ll offer some closing thoughts on the other side of it.

The Kellogg’s Strike

Kellogg’s, the maker of life sustaining health food like Pop Tarts and Frosted Flakes. Stuff that’s really good for you. No, not just good. They’re Greeeeaaaat!!!! (Kill me)

Taking a look at their topline financials we see some pretty, pretty healthy stuff. Just like their Pop Tarts. Kellogg’s turned a profit of about $1.7 billion on $13 billion in sales in 2020. And, good news folks, revenue and profits are set to increase this year by about 9%, as they’ve already posted a profit through three quarters in 2021 of $1.4 billion!

And yet, on the ground, the workers at Kellogg’s are battling management over contract negotiations that would see a split in tier compensation for new and less tenured workers at their plants. As the Jacobin reports:

“Sales are up; Steve Cahillane, Kellogg’s CEO, made roughly $11.6 million last year; and the company recently authorized $1.5 billion in stock buybacks to boost shareholders’ returns.”

The dispute between labor and management boils down to Kellogg’s desire to create a tier system that would provide fewer benefits to new members. The workers contend that this would create ill will between tiered members and put tenured members on the chopping block during periods of cost cutting. And, by the way, that’s exactly why governments and companies do this. What should be lauded about this is that the Kellogg’s workers aren’t fighting for their individual, current rights. They’re fighting for future members. If there was ever a noble struggle, this is it.

But that’s obviously not the way Kellogg’s views it. The world is a mess, supply chains are disrupted and costs are rising. They view their actions as timely and responsible, ultimately protecting their more important constituency: Shareholders.

And here’s where I want to dissect the Wall Street insider speech so we can all understand how this goes in real-time. Let’s go through this together and translate what Kellogg’s CEO Steve Cahillane is saying to Wall Street in a recent investor relations interview with CNBC.

Carl: “You know, the market’s been hungry for examples where a company can make up for increased input costs through better mix, better pricing—it sounds like that was your story.”

Steve: “Yeah, it was. We had, we had a very strong quarter. You know, we drove volume, we drove price, we drove mix. Uh, you know, our brands held up very well despite all the supply chain challenges, you know, and that’s what we’ve been doing.”

So, to begin, Kellogg’s had a very strong quarter. And that’s on top of a very strong trailing 12 months and growth in revenue and cash flow, as we said before. The key here is that they drove volume, price and mix. Driving volume and mix means that they sold a lot across their portfolio. More sugary cereal and Cheez-Its to the world. No great innovating thing, they just sold a lot. It’s the price driver that should get your attention.

He said volume increased, which contributed to the growth of sales. Makes sense. But they also raised their prices. And we know that was just a decision to drive profit because he ends the clip saying they did all of this despite supply chain issues, which makes one wonder whether they actually experienced any issues or whether they’re just using that as a talking point. Because if you had supply chain issues, I mean real ones, you wouldn’t drive more volume. You would drive less. It’s perfectly rational to increase prices to maintain margin if you’re having volume issues. But here he is saying they had no problem distributing and increasing volume, and they raised prices. If you listen carefully, you’ll hear Milton Friedman laughing in his grave. Let’s continue.

Steve: “We’ve been investing in our brands and making sure that they stay relevant with consumers, and it’s allowed us to have a very good quarter driven by some of our biggest brands like Pringles, Cheez-It; our international business performed exceptionally well, led by our EMEA region, highlight on Africa. Our Europe business had 16 consecutive quarters of growth, uh, really outstanding performance in the UK and Russia. So broad-based across the patch for us, but as you pointed out, price mix was, was clearly an important driver for us.”

Sixteen straight quarters of growth in Europe, and Kellogg’s is doing the lord’s work by introducing Pringles and Pop Tarts to the African continent. No vaccines for you, but here’s some diabetes in a can! No hint of supply chain issues there, but at least he acknowledges that in addition to expanding into new markets, they were able to raise prices despite little to no pressure to do so. Just greed. That’s what greed sounds like.

Carl: “How sustainable, then, is that over the coming quarters?”

Steve: “Well, we think it’s sustainable, Carl. I mean, we’ve been investing, as I said, in our brands, we’re innovating, and it’s been driving very good performance in market and with our customers. There’s obviously a lot of supply chain challenges, a lot of things to overcome, but when we look at where we’ve been over the course of the last several years—you know more and more our snacks business especially stands out, and it’s really been driving sustainable, robust, dependable growth for us and we see that continuing.”

There’s that fucking supply chain thing again. It’s pretty much all we’ve heard about in corporate media. And I’m fully acknowledging that there are still inventory issues and buildups at the ports, companies are struggling to find containers and we’re working through existing stockpiles of inventory all over the world. But… we’re talking right now about fucking potato chips and Frosted Flakes. You don’t get to say that you’re obviously working through supply chain issues while saying you’re exploding in new international markets and increasing the volume of sales. Those two things do not go together. But that’s Wall Street everyone. If there’s a prevailing sentiment, true or not, go with it and claim it for your own.

Morgan: “Steve, let’s talk a little bit about the labor piece of the puzzle right now, the fact that your workers that are unionized, that are striking, have rejected the most recent offer you’ve put in front of them. How’s that factoring into your forecast, and what is it going to take to see a deal actually manifest?”

Okay. Game on motherfucker. Here we go!

Steve: “Yeah so, you know, we put the most reasonable assumptions in, and that's that we come to a deal soon. And what I’d say about that is, you know, we’re obviously still in negotiations with our people, we want our people back. I mean, they performed so heroically throughout the course of the last 18 months.”

STOP! Fuck you. Fuck you and your essential worker, “you performed heroically” bullshit. Fuck you, fuck your $11 million paycheck and fuck your pandering. Heroes when you need them. Shitheels when you don’t. Continue.

Steve: “The workers that we’re talking about are specific to our four U.S. cereal plants, and they have right now a contract that’s expired that has industry-leading wages and benefits. And we are putting in front of them—we put in front of them increases, uh, in compensation. So there’s no takeaways despite what, you know, some may have said. There are no takeaways, it is an excellent offer. We want our people to see that offer, we want our people back and, uh, we’re working very, very hard to make that happen.”

That’s not the issue, Steve. That’s what makes this a noble fight and what makes you a fucking pariah. These workers are standing up for the ones to come, not themselves. He’s reframing the issue in the most patronizing way possible, saying they’re heroes, but also greedy. The next bit is ol’ Steveo answering a question about inflation and if he thinks it’s going to be around for a while.

David: “If I recollect correctly, the last time we had you on when we talked about inflation, you sort of indicated, ‘yeah you can call it transitory but in my book, transitory is going to be for quite a while.’ I wonder, given what you’re seeing right now, what your expectations are and whether they’ve changed at all when it comes to broadly speaking inflation.”

Steve: “Yeah, thanks David. I hate to have been right on that one, but transitory is for some period of time and so we don’t, we don’t see any kind of mitigation, um, in commodity pressures, in cost pressures. And what you’re seeing is all these friction pressures, you know, logistics, all things supply chain, uh, still being disrupted, and so we’re planning on it continuing for the foreseeable future. So we’re not predicting an end to it, and we’re looking towards productivity and what we call revenue growth management as a way to mitigate and protect our margins going forward, but clearly 2022 is not going to change magically with the turn of the calendar. And so we’re, you know, we’re forecasting and preparing for ongoing challenges.”

Friction. Commodity pressures. Logistics. Supply chain issues. Just the fucking kitchen sink explanation behind this:

David: “And how does price figure into that equation?”

Yeah, Steve. How does price figure into this equation? Look at this whole thing here. It’s masterful:

Steve: “Well price, price is important. Price is one of the levers for us and, you know, we don’t talk prospectively about pricing, but when you look at what we’ve done over the course of this year, we’ve actually been ahead of it. So we’ve been able to cover all the commodity types of costs that we’ve seen and we do that through, uh, price, we do that through mix, we do that through assortment. All sorts of things. But what we really try and keep, um, at the center plate is our consumer, and making sure that we’re driving value for the consumer. So, as we need to take price, we talk about the right to take price or the deserving, um, of taking price, asking consumers to pay more because we’re giving them more in terms of innovation, in terms of value.”

Price. Mix. Assortment. “All sorts of things.” What the fuck does that actually mean? It’s not all sorts of things. It’s just raising prices. Underlying demand is strong. They have no supply chain issues, as evidenced by their increase in volume and new markets. They are inflation. He said it directly. They “got ahead” of commodity pricing issues. How? By raising prices. You, Steve. You are inflation. If you got ahead of it, then you’re the driver. You see how this shit works? Talk about opportunistic capitalism. People are home. Locked in. Eating more snacks. So they just raised their prices and conveniently blamed it on factors that are not their factors. They saw a chance to raise prices, and they took it. But don’t worry, because he’s sensitive to the consumer.

The “right to take price?” You deserve a raise because you drove value? If you give the same product at a higher price, that’s not the definition of value, Steve. And “taking price?” What the fuck is that? Innovation? Tell me how your latest Cheez-It innovation was so groundbreaking that you deserved the right to “take price?” This is standard Wall Street euphemism bullshit. Taking price? Here’s the real translation.

We raised prices because we could and no one could stop us. Our supply chain is fine, in fact we’re humming. More business than ever. More volume than ever. And we raised prices because we wanted to. That’s the honest response here, but you’re listening to a masterclass in Wall Street fucking bullshit. And they’ll turn all this shit around on the heroic workers by saying that they’re greedy.

That’s why we have inflation.

That’s why we hate workers.

That’s why the corporate media is complicit in these narratives.

That’s why we need financial and news literacy training to spot this fucking bullshit a mile away.

And that, my dear Unf*ckers, is why we need unions.

Some Ruminations on the Ongoing Struggle

Child labor. The fight for eight hour days. Strikes and scabs, sit ins and riots. On the Waterfront and Norma Rae. Racism. Sexism. Communism and socialism. From goat to hero and back again. Rinse. Repeat. The story of unions is the story of America told in multiple, bloody chapters. But there’s one consistent theme that emerges from all of this. Workers are foils, pawns in a game they don’t know they’re even playing.

When the titans were building the nation in the industrial era, Washington turned a blind eye to the abuse of children and workers. It wasn’t until the Great Depression that our government and owner class turned to the workers to ask for their help. In return, they got a New Deal. If they were white. It was, after all, still America.

When the war came, the workers went abroad to fight, so the government turned to women and the black community to ask for their service. They made posters and short films about them. They, too, got a new deal.

When the fighting ended and the economy was booming, our true colors were once again revealed. We took our racism up a notch. Sent women back to the home. Passed anti-organizing legislation. And called anyone who organized a communist.

Then they chipped away at alliances. Turned to the states to compel them to split black and white union brothers and sisters apart and turn them on one another. The civil rights movement went one way, workers went another. And as the economy morphed from industrial to financial to service, the management class turned on lumpenproletariat. They were the cause of inflation. They were the cause of work stoppages. They were inherently corrupt and therefore un-American.

So when the 90s came, no one wept for the workers as labor was shipped abroad. Famed economist Joseph Stiglitz writes:

“Globalization, in the matter in which it has been structured, has diminished the ability of unions to gain pay raises for their workers, and this reduction in their effectiveness has contributed to diminished membership. Union leaders sometimes do not adequately reflect the interests of their members, referred to as the principal agent problem—something that arises in all organizations in the presence of imperfect information and accountability.

“The weakening of unions has not only led to lower wages for workers but also eliminated the ability of unions to curb management abuses within the firm, including managers paying themselves exorbitant salaries at the expense not only of workers but of investment in the firm, thereby jeopardizing its future. What John Galbraith had described in the middle of the twentieth century as an economy based on countervailing power has become an economy based on the dominance of large corporations and financial institutions—and even more, of the power of the CEOs and the other executives within the corporation.”

Today, more than half of union members live in just seven states. And those states account for one-third of wage and salary employment nationally. These states, the ones that still value unions and labor—California, New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Michigan, New Jersey (that’s painful to say) and Ohio—these are the states that are driving this economy. We’re the ones holding shit up because we value our workers slightly more than the right-to-work states that demonize labor.

I’m no pollyanna when it comes to union corruption and things that have gone too far. Some of the absurdities in the state pension systems are crushing state budgets. The police unions have far too much power. There is corruption in the union structure, but it’s important to remember that this was intentionally created by separating classes of workers and giving too much power to the top brass. Unions, like government and corporations, are made up of people and people are corruptible, especially when you create the perfect circumstances for it to thrive.

People like Elon Musk, Ben Shapiro and the dicknoggins over on the Fox Business channel like to talk about free markets and innovation. But I’ve hammered this point before and will continue to do so. You show me a billionaire or multinational company today, and I will draw a straight line directly back to the government program that birthed it. Listen to Economic Update with Rick Wolff this week where he talks about the innovative billionaire myth.

I live in New York. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard people bitch about unions. They always say the same thing.

“They’ve outlived their usefulness.”

“They’re corrupt.”

“Trade unions add so much cost to a project you can’t make money.”

“Unions killed innovation and competitiveness.”

“Unions are the reason China is killing us.”

“Why would I hire union just to pay one guy to plug something in and another to watch him?”

The funny part about this is that almost every time I hear these phrases, they’re being uttered by a super wealthy person. I’m not kidding. I literally know multimillionaires and centimillionaires (I don’t have any billionaire friends yet) who will talk about their latest commercial project and bitch about unions fucking it up. Then they get into their Carrera SUV, leave their 10,000 square foot homes and hop to the private airport to get away from it all for a long weekend.

It’s fine. I really don’t give a fuck about people’s lives or listening to them bitch about how they made a million less than they could have on a project. I just marvel at the lack of self awareness.

But that’s the thing. Millionaires and billionaires aren’t the only ones who hate unions. Working class people who aren’t in a union despise them, as well, because they hold them responsible for the price of gas and milk. The government, for all of their talk during campaign season, clearly hates the unions, as well, because they take their money, then actively legislate against them.

It’s what bothers me about all of the emphasis in the news right now on workers. If you just rip through the headlines, you would think unions are making a comeback. Labor is back, baby! But the examples we gave in the beginning of the show are pulled right from the AFL-CIO website as the most notable examples of the year:

-

32 drivers in Maine.

-

A bookstore in L.A.

-

A new contract at a distillery in Kentucky.

-

90 librarians in Ohio.

-

Writers at The Atlantic.

-

Prevailing wage for government construction in Michigan.

-

A Starbucks. In Buffalo.

From 30% in the 50s to 10% today, and declining, no matter how many librarians and baristas join a union. The larger pattern of negotiations is to hold the line. Protect what’s there. Never more, never moving forward. Just holding. The cost of living increases every year, but wages don’t. Union or otherwise. That’s not the system we have. Because we hate workers.

Yes. We should all support union shops. As I just noted from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the states with the highest membership are the ones holding this shit together. We should fight for the legislation that is currently on the fucking table and could be passed tomorrow if Biden really cared about workers and the Democrats had any guts. That’s perhaps the easiest part of the equation, despite the intransigence and lip service of the Democratic Party. If we don’t keep adding to the ranks of the Progressive Caucus and demanding change in the voting booth, we’re simply resigning ourselves to more of the same.

Here’s the unpopular conclusion I’ve come to for the moment. The fact of the matter is that we might be too fucked up as a nation to hope for more than this. Something we’re going to investigate deeper in the new year is this strange version of libertarianism that runs through our politics and infects us all. We call it things like liberty and freedom. Don’t tread on me bullshit. Build what you want. Where you want. Shoot who you want. Don’t pay taxes if that’s your thing. Just live wild and free. And no matter how much you might be suffering, there’s a weird pathology that makes it okay so long as you see others who are worse off. It’s mean. It’s self-defeating. And it’s uniquely American, as far as I can tell.

It took a Great Depression and a world war to bring labor to the table. Then, almost all of the gains made in this time have been slowly removed from the table, with only scraps remaining. I think we need to look beyond unions, while supporting their efforts to maintain what’s there, and re-examine a fresh New Deal for all Americans.

We’re not suddenly going to become a labor economy again. The professional-managerial class, the PMC in American Capitalism, is very real and not likely to cede ground to bring back manufacturing beyond what currently exists. What we can do is borrow from the past successes in the labor movement. Messaging. Organizing. Advocating for universal healthcare, more robust safety nets, paid time off and family leave, the nuts and bolts of a properly functioning market system with failsafes built in for periodic convulsions as we transition to a new and greener economy.

We’ve built enough fundamental understanding of our economic infrastructure to know that when we support one class over another—and that could be one race, one gender, one labor class, anything that connotes “otherness”—it will be met with force from the monied class and lobbyists in Washington. But as we learned from Occupy, when we change the conversation through the use of language and put the 99% against the 1%, it can change perspectives. That’s where Dr. King landed before his life was deliberately cut short. American issues boil down to class. Us versus them. Equity is greater than any marginal attempts to bolster a particular subset of the nation. In other words, we all rise together or risk falling apart when attacked individually.

Pressure Congress on H.R. 842 to help hold the line.

Stop calling workers heroes because it separates them and makes them vulnerable.

There’s only one union that matters. The 99%.

Here endeth the lesson.

Max is a basic, middle-aged white guy who developed his cultural tastes in the 80s (Miami Vice, NY Mets), became politically aware in the 90s (as a Republican), started actually thinking and writing in the 2000s (shifting left), became completely jaded in the 2010s (moving further left) and eventually decided to launch UNFTR in the 2020s (completely left).