The Black & Jewish Divide in America: The Fractured "Grand Alliance"

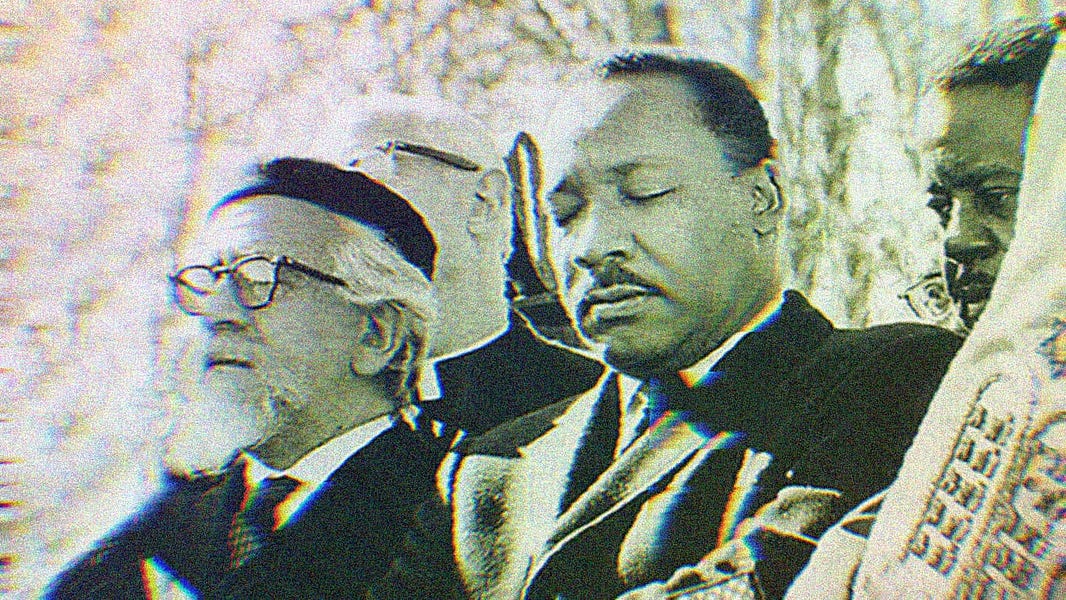

Image Description: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel walking arm in arm.

Image Description: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel walking arm in arm.

“We begin with the conflict between Jews and Blacks in America. The tension in the United States has been growing more and more over the last few years from events like the Crown Heights riots to the dissension over issues like affirmative action and Zionism and Black separatism, the two groups have found themselves at odds.”

Everything old is new again. This is Charlie Rose’s introduction to a conversation between Cornel West and Michael Lerner in 1995. That’s more than a quarter century ago, and we’re having much the same dialogue today, though the language has devolved as our media landscape circles the bowl of intellectualism. So, we’re nearly 28 years from this conversation, which was about 28 years from what can be viewed as the original fracture between the progressive Jewish movement and the rise of the Black power movements in the United States.

The difference today is the supposed democratization of the media has allowed these conversations to take root in dark and disaggregated places. Kanye West, or Ye, may have brought them to the surface, but they were happening already. In uncontrolled, unmoderated spaces with little to no historical context.

For the moment, Ye seems to have both ignited and suppressed the fire by taking the conversation into taboo territory, proclaiming his admiration for Adolf Hitler. Provoking the Jewish community with antisemitic language was dangerous on many levels for all of us. And because of his position in pop culture, it was terrifying for Jews in this and other countries. But he veered into such radical hate speech territory that the only outlets available to him and his new white supremacist sidekick Nick Fuentes are far right conspiracy influencer vlogs.

That’s all the time we’re going to spend on Ye because it benefits literally no one to propagate his vitriol. But I want to highlight one brief excerpt to illustrate something chilling. In an interview with Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes, who has been essentially deplatformed everywhere but Elon’s garden of hate, McInness tries to corner the rapper by asking if there’s any use for Jews in society. This was Ye’s reply:

“Jews should work for Christians. I'll hire a Jewish person in a second if I knew they weren’t a spy and I clicked through their phone and followed them to their house and have a camera all in their living room. (Laughter)”

Given his recent antics, the response wasn’t surprising. What caught me off guard was the roar of laughter that followed. I realize the venue was prime for this type of response, but it demonstrates a level of insensitivity that surrounds the Jewish people in this type of commentary. A shockingly casual antisemitic response to a shockingly virulent antisemitic statement.

Throughout the media and cultural landscape, it continues to be safe to peddle in antisemitic tropes despite the prevailing narrative that no one is allowed to criticize Jews.

“Early in my career, I learned that there are two words in the English language that you should never say together in sequence. And those words are ‘the’ and ‘Jews.’” -Dave Chappelle on SNL

In all sincerity, it is fraught territory to weigh in on this issue, having no agency in either camp. But I’m hoping that my perspective as an outsider allows me to serve as a reliable narrator on another perspective that’s getting lost in the discourse. In order to reach this point, we’re going to move carefully through an incomplete but important history of the Jewish and Black relationship in America from the Civil Rights era forward.

We’ll address where Israel fits in the discourse and the origins of the Pro-Palestinian support in parts of the Black community. And I’ll be leveraging the work of different thought leaders in both communities to highlight their respective feelings and beliefs.

Chapter One

The ties that bind us together.

There’s a saying in journalism. Don’t bury the lede. Meaning, say what you mean up front, then go about supporting it. You don’t want your point to get lost. So here’s the lede: In 2017, a mob of young men at the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville moved seamlessly between “Jews will not replace us,” and “white lives matter.” That’s the subtext that’s missing in the conversation about Black people and Jewish people today.

In any conflict, it’s important to ask who stands to gain the most from it. And, in this case, it seems perfectly clear.

So let’s go back. Back to when the supposed “Grand Alliance” was at its zenith during the Civil Rights era. There are two iconic moments from the ‘60s that many came to define as the examples of Black and Jewish solidarity in the United States.

One is a photo of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the march from Selma to Montgomery walking arm-in-arm with white and Black leaders, including Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent progressive figure in Jewish-American history. The other is the murder of southern Black activist James Chaney and Jewish activists from New York, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, in 1964. Their disappearance galvanized the nation, and the subsequent uncovering of the bodies and conspiracy to murder the men would be memorialized in the film Mississippi Burning.

Many Black and Jewish intellectuals have downplayed the significance of these moments in terms of their defining nature. It’s felt by many that Jewish leaders romanticize these events, while Black leaders tend to downplay them. And, in either case, it’s most certainly reductive, but that’s the nature of whitewashed history. Even if the truth lives comfortably in the middle, I think it’s fair to say that relations have most certainly gone downhill since this time.

The alliance in the 1960s was quite natural, and forged out of necessity and like-mindedness on several issues. And those issues were equality, justice, racism and the war in Vietnam. At this time, the interests of Black and Jewish Americans were fairly aligned in socio-economic and class terms.

Origin Stories

Jews from various backgrounds and nations had been migrating to the United States since the 1600s. The next four centuries would be punctuated by waves of Jewish immigrants coming to America for both economic opportunity and sanctuary. The largest wave was of Ashkenazi Jews, meaning Jews of Eastern European descent, after World War I. Jewish immigrants followed a similar trajectory to most new Americans. In other words, they weren’t exactly received with open arms.

Jewish immigrants would be met with the same suspicion as most new groups, and often sought refuge among their own people and culture in the ever expanding urban centers of America. With one key distinction. Jews were met with a double dose of anti-immigrant and antisemitic sentiments that would suppress their ability to economically assimilate, as many other predominantly white cultures would do within one generation. This is a crucial element of our story.

Black Americans, of course, had no origin story of their own when it came to willful migration. They were compelled by force and brutality to America. Most Black Americans were unable to fully trace their roots back to a homeland. Generation after generation, through bondage and supposed freedom, Black Americans would remain shackled. Literally at first, then figuratively through disenfranchisement, segregation and incarceration. As generation after generation of white immigrants to America moved from poverty to prosperity, Black Americans were halted at every turn. We litigated the economic argument in our Economics of Racism episode.

Today, Jewish Americans enjoy a higher standard of living relative to other identity groups. That’s not to say there aren’t Jews who live in poverty. But, on balance, Jewish household income is among the highest of peer groups of race and religion. But this was not the case for most of the Jewish experience in the United States. In fact, most Jewish immigrants worked in horrific conditions and were relegated to the low end of brutal trades like the garment industry.

Over time, they found work in other service areas of the economy, such as healthcare, education and the entertainment industry. This isn’t a reinforcement of a stereotype, as these are still the industries in which Jews are most represented, according to Pew employment research.

These early experiences of trying to forge a path forward in a society that refused to accept them in most visible industries, helped foster the modern tropes we often associate with American Jews. The liberal college professor, the doctor, entertainment agent and so on. In many stereotypes, you can find a kernel of truth. But these stereotypes often take on a life of their own and sometimes become a self-fulfilling prophecy that remains tethered to a group long after that kernel is gone.

The other notable characteristic of Jewish immigrants prior to the Second World War was liberalism. Judaism is steeped in justice and equality. Both in religious text and cultural tradition. Far more than the other dominant monotheistic religions of the world. As such, prior to the war, cultural and religious Jews were often sympathetic to socialist and communist causes, traditions they brought with them from Europe after the first World War.

They were also a people without a homeland. There was no rallying cry for Israel because there was no Israel yet. During the period between the two great wars, stories were leaking about Jews being subjugated and even hunted in Europe. When American Jews looked out for empathy and support, there was one group that required no explanation of their plight. In Black communities, Jews found solidarity and commonality.

Economic Alignment

After the war, Jewish and Black people in America continued to find common ground in the 1950s during the communist witch hunts that put government officials, along with several high profile Jews in entertainment and academia, on trial in both real court and the court of public opinion.

Before we get to the turning point in the 1960s, let’s examine the overlap of economic experiences between the two communities for a moment. Think of where Jews in this country were relegated or allowed to work and prosper in the 20th Century. Entertainment, medicine, finance and academia. Now, think about the areas that Black people were allowed to work and prosper. Service and entertainment.

The most visible grievances in the Black community today where Jews are concerned is in entertainment. When we first understand that this was one of the areas of intersectionality between Jews and Black people in the country—the area of our economy that they were allowed to participate in—we can more easily understand the roots of a fracture in this industry. The stubborn trope that the media and entertainment industries are controlled by Jews has that small kernel of historical truth we talked about. If anything, it’s the world “control” we should take issue with.

“Anyone in media? Who’s the top in that field? Anybody a rapper in the house? Oh, there’s rappers… I mean, uh, you can rap and there’s nothing wrong with that. But at the top of that are those that control the industry and if you have Hollywood ambitions… Broadway ambitions… Who’s the top of that? Same people.” -Louis Farrakhan

Jewish representation in the media and entertainment is a factor of historical legacy. Shunned from most industries, save for the few we mentioned, Jews carved out a meaningful place in just a handful of businesses. To suggest Jewish people have control over these industries is laughable, and the perpetuation of shameless stereotypes. It’s like saying enslaved Black people had control over the fashion industry because they picked the cotton for garments. Yes, it’s that stupid. Sorry if that hits anyone’s ears the wrong way.

There’s a more direct and logical extension of thought that we’ll get to in the next section, but for now, if we carry this particular line of thinking through to a logical place, then it becomes clear why Black entertainers who have the most amplified voices in today’s culture have a bone to pick with the Jewish people. For decades in the entertainment industry, Black artists were taken advantage of in stunning ways. And, in some cases, it was by Jewish executives. It was commonplace for Black artists to lose the rights to their work even when they thought it was protected. Every successful genre of music established by Black artists was appropriated by white artists, with little credit and usually no remuneration.

So today, when we see prominent Black celebrities like Dave Chappelle, Kyrie Irving, Meek Mill, Ice Cube or Jay-Z dip into Jewish conspiracy territory, they’re tapping into a bifurcated attitude. One is the long held cliche that Jews have profited from their work. The other is that Jews paved the way for how Black industry can develop. In these short verses alone, for example, Jay-Z is expressing admiration for Jewish prosperity, but doubling down on a tired stereotype in doing so:

“You wanna know what’s more important than throwing away money at a strip club? Credit.

“You ever wonder why Jewish people own all the property in America?

“This how they did it.

“Financial Freedom my only hope.

“Fuck living rich and dying broke.”

There are many examples of antisemitism and anti-Zionism in Black artistry, but I wanted to use someone like Jay-Z, who is a transcendent cultural touchstone, to demonstrate how normalized and mainstreamed these sentiments are.

We like to tell ourselves stories and fables about people and groups who defied the odds. It’s what makes stories like Motown so important. But these stories are often sold as the norm, rather than the exception to the rule. Like claiming we’re in a post racial period because Barack Obama was President. Or economic justice has been achieved in entertainment because Jay-Z is a billionaire. In this way, these stories aren’t helpful, because they obscure the reality on the ground. And the reality for Black artists in America has been, and remains, historically diminished relative to their white counterparts.

All of this is not to suggest that Jewish people as a rule are, or were, in any way responsible for this phenomenon. Participants. To an extent. But we need to eliminate absolutist rhetoric on all sides to move forward with productive dialogue.

With all that said, let’s move into the ‘60s; the inflection point in the narrative.

Chapter Two

The lies that pull us apart.

“I don’t know what most white people in this country feel. I can only include what they feel from the state of their institutions. I don’t know if white Christians hate negroes or not, but I know that we have a Christian church which is white and a Christian church which is Black. I know, as Malcom X once put it, it’s the most segregated hour in American life—high noon on Sunday. That says a great deal for me about a Christian nation. It means I can’t afford to trust most white Christians and certainly cannot trust the Christian church. I don’t know whether the labor unions and their bosses really hate me. That doesn’t matter. But I know I’m not in their unions. I don’t know if the real estate lobby has anything against Black people, but I know the real estate lobbies keep me in the ghetto. I don’t know if the Board of Education hates Black people, but I know the textbooks I give my children to read and the schools that we have to go to. Now this is the evidence. You want me to make an act of faith. Risking myself. My wife. My woman. My sisters. My children. On some idealism which you assure me exists in America, which I have never seen.” -James Baldwin on the Dick Cavett Show in 1969

The fragile alliance between Black and Jewish activists locked in struggle against economic oppression, domestic violence and anti-war protests reached a peak in the mid-1960s. This is the brief moment in time that is taught to us in school, memorialized in federal holidays and days of remembrance. History recalls this as a crescendo to be celebrated. Perhaps it was. But, below the surface, there were splinter movements gaining momentum and advocating more radical change and fomenting discord among the ranks of the Civil Rights Movement.

For decades, the establishment media and political apparatus have busied themselves crafting a convenient narrative for this era. First, by watering down the more radical activism of Dr. King. By portraying groups like The Nation of Islam, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and The Black Panthers as fringe players. Then, by erasing them altogether from official narratives, left as subjects of documentaries and published works in academia. In reality, these movements were galvanizing young Black Americans in significant ways that can still be found today in Black art and culture.

Even in the late 1960s, as the fragile Civil Rights alliances began to break down, the rise of these Black movements were aided by Jewish intellectuals like Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky, who promoted the work of Black intellectuals like Marcus Garvey and W.E.B DuBois and collaborated with rising figures like Kwame Ture, Angela Davis, Fred Hampton and Elaine Brown.

Leaders of the Black Power movement in the United States coincided with the rise of the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa and opened Black Americans to the idea of a global Black identity. At the same time, Jews were beginning to realize the profundity and potential of Israel during its defining Six-Day War in 1967. Here’s journalist and scholar Ben Ratskoff talking about this period:

“In the late 1960s, it’s a rather overdetermined moment. I mean, there’s a lot of things happening at once, right, which is that… SNCC is expelling all of its white members, losing all of this funding from white Jews at the same time that the ‘67 war in Israel and Palestine, right, is happening. And it’s shifting kind of this anti-colonial global consciousness at the same time that Black Panthers are concentrating in Algeria, which is like a site of solidarity with Palestine. So it’s like this incredibly over-determined moment of all these different factors.”

The Suburban Split

Domestically, something else was happening in American cities. Suburban sprawl. In the 1950s, the federal government worked diligently with state governments and developers to encourage the great migration from cities. Initially, white Christian veterans were given early and unconstitutional access to these developments. Then, came the invention and proliferation of credit through personal lines and mortgages. Home ownership exploded throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s, and for the first time in America, Jews were gaining access to the so-called American Dream.

Jewish partners in the Grand Alliance didn’t fare as well in this period. Redlining was still the official/unofficial policy of the real estate and insurance industries. Mortgages were offered at higher rates for Black buyers than white buyers. Credit cards were denied to Black applicants, even after the practice was made illegal by using the real estate redlines as reason for approval or denial. For the first time in modern U.S. history, one of the last economically marginalized groups was making inroads, while the other appeared to be backsliding once again.

Figures like Louis Farrakhan would feed into the economic and political inequality by scapegoating the Jewish people. Not ALL Jewish people, he would say. Just the “satanic” ones who control the media, education, medicine and entertainment. They are the reason you get so little from a record deal. Why you wait longer to be treated in the hospital. Why you cannot access higher education. And why you are demonized in the corporate media. Like all propaganda, lies that are repeated take on an air of truth to the listener, when that’s all they hear.

Here’s where perspective matters. While leaders like Farrakhan have absolutely had a demonstrable impact on the psyche of some Black Americans, there was the economic and political reality of the post Civil Rights era that was evident to all. Jews were getting ahead, retaining their culture, rallying around a homeland. And many in the Black community felt as though they had closed the door behind them.

To illustrate this far more eloquently and powerfully than I ever could, I want to read a passage from one of James Baldwin’s most impactful essays. Forgive the anachronistic language, but Baldwin’s words are sacrosanct and deserve to be preserved.

“In the American context, the most ironical thing about Negro anti-Semitism is that the Negro is really condemning the Jew for having become an American white man—for having become, in effect, a Christian. The Jew profits from his status in America, and he must expect Negroes to distrust him for it. The Jew does not realize that the credential he offers, the fact that he has been despised and slaughtered, does not increase the Negro’s understanding. It increases the Negro’s rage.

“For it is not here, and not now, that the Jew is being slaughtered, and he is never despised, here, as the Negro is, because he is an American. The Jewish travail occurred across the sea and America rescued him from the house of bondage. But America is the house of bondage for the Negro, and no country can rescue him. What happens to the Negro here happens to him because he is an American.

“Finally, what the American Negro interprets the Jew as saying is that one must take the historical, the impersonal point of view concerning one’s life and concerning the lives of one's kinsmen and children. ‘We suffered, too,’ one is told, ‘but we came through, and so will you. In time.’

“In whose time? One has only one life. One may become reconciled to the ruin of one’s children’s lives is not reconciliation. It is the sickness unto death.

“The crisis taking place in the world, and in the minds and hearts of black men everywhere, is not produced by the star of David, but by the old, rugged Roman cross on which Christendom’s most celebrated Jew was murdered. And not by Jews.”

Most critical interpretations of Baldwin are that he was not an antisemite; he was anti-white Christian establishment, and to the extent that Jewish Americans had assimilated into these structures, he was critical.

Here, he is using language that remains difficult for many to hear even to this day. In no way do I want to distill his words. Again, that would be heresy. But what he conveys is the sentiment in the Black community that Jewish assimilation was due to whiteness. And, while remembering past traumas and maintaining a cultural identity is the right of any group, these factors do not absolve a people from the sin of whiteness in America.

Baldwin isn’t taunting anyone here. Nor is he relying on tropes and stereotypes. He’s merely identifying that which is impossible for white people of any culture, background or religion to know about the Black experience in America.

Chapter Three

Israel

Jonathan Weisman, author of (((Semitism))) Being Jewish in America in the Age of Trump, writes about the fracture in the alliance in sobering terms:

“For years now, it has been the only question in the Jewish political world: Where do you stand on Israel? The American Jewish obsession with Israel has taken our eyes off not only the politics of our own country, the growing gulf between rich and poor, and the rising tide of nationalism, but also our own grounding in faith.”

Weisman is tapping into one of the most important elements of Judaic tradition: Justice. Anyone with even the vaguest knowledge of Judaism knows that social justice is core to its tenets. A critical note here. I’m referencing the conservative and reformed religious systems, and not Orthodox. I’m less familiar with the practices and interpretations of Judaism in the Orthodox community, though tension between this group and the Black community in urban settings certainly contributed to the divide.

So, to be clear, I’m speaking of the secular and more liberal religious interpretations of Judaism as prescribed in modern Jewish culture. Likewise, Weisman is speaking a hard truth about Jewish representation in American political life, and that’s the almost single minded focus on supporting Israel above all else.

Having placed the Grand Alliance in some historical context, we must push ourselves to touch the third rail. One’s stance on Israel has become a litmus test in today’s society, and it’s very much a part of the cleavage between the Black and Jewish communities. It’s central to the criticisms of the conspiracy documentary that Kyrie Irving shared, central to the antisemitic lyrics found in certain parts of Hip-Hop culture and central to the divide in the Democratic Party.

Of course, this has been a sticking point in the Black Power community for years. Non establishment Black leaders like Ture, Malcom X, Angela Davis and so on have been aligned with the Palestinian struggle for decades. A tradition carried on by Black leftist leaders like Cornel West and only more recently adopted by younger leftists inspired by the Boycott, Divest and Sanction movement (BDS) that was core to the original policy statement of Black Lives Matter, as an example.

Weisman explores this territory as well, saying:

“For young progressives on campuses across the country, fealty to the BDS movement is just another item to check off as they make their way down the list of liberal causes: Black Lives Matter, immigrants’ rights, LGBT rights, gender sensitivities, opposition to all manner of cultural appropriation, and intersectionality. Sympathizing with the oppressed is the job of the ‘woke’ generation, but although Jews have been exiled, isolated, disenfranchised and massacred since Nebuchadnezzar, we are no more due the sympathies of the Left on campus than we are due special treatment in higher education admissions or workplace hiring. To the advocates of BDS, Israel’s current military strength and right-wing policies negate three thousand years of hatred.”

This is the part that resonates with me personally and likely places me partially at odds with both the right and left on the question of where do you stand on Israel. To deny Israel’s right to exist in the world is to be ahistorical and ignorant.

Perhaps it’s fair to adopt Baldwin’s perspective to criticize Jews in the United States who use Jewish history to absolve them of abandoning issues of justice and equality and assimilating into patriarchal white power structures. And perhaps Weisman is right to chastise the left for denying Israel’s right to exist, to the extent that sentiment lives in certain pockets of the left.

And maybe both of these truths can live together. Certainly, neither one should erase our ability to be critical of the power structures of Israel, just as we have the right to criticize the power structures in America. For many Jews in America, any criticism of Israel’s treatment toward Palestinians is an indictment of Judaism. It is not. To call Gaza an open air prison is not antisemitic. Just as calling Hamas ruthless and corrupt isn’t an indictment of the Palestinian people.

The UN special rapporteur’s condemnation of Israel as an apartheid state isn’t an act of hate. It’s a reflection of reality. But the conditions that support this view are not perpetrated by Jewish people, but rather the government of Israel. For, if it were the former, then the world would have condemned the Belgian people forever for the murder of more than ten million Congolese. Germans for the murder of six million Jews. Americans for the near extermination of native people.

This ties into a persistent thread in the Black Power movement regarding the right of Jews to even claim a homeland in the Middle East as some sort of restitution for the Holocaust:

“Let me tell you a tactic of Zionism. What they do is that every time you say something, they bring out Hitler. You understand? And they make you feel scared about Hitler. Okay, if Hitler killed as many Jews as he did then what the Jews should do is take Germany. Why you go to Palestine? The Arabs ain’t done nothing to you.” -Kwame Ture debating a Zionist in 1973

Weisman picks up on the modern debate of legitimacy noting that, “American Jews are still loath to see it, but the Israel diversion is proving to be a trap. Zionism—Jewish nationalism—cuts both ways.”

But, Weisman continues, the trap is about nationalism and must be separated from the religious, cultural and spiritual realm of Judaism.

“It is Israel, they say, that is illegitimate: a colonial, racist state injected into the Middle East by Western powers reeling from guilt over the death of the 6 million. Sadly, European intellectuals say, the Jews have used the Holocaust as a moral bludgeon to justify all manner of evil deeds by the illegitimate Jewish state, and for that we can have no tolerance. And that intolerance has led many in Europe—and some in the American academy and fringe left—to make a dangerous leap: the Jews in our midst must either renounce Israel or suffer the consequences that they themselves have brought on—the onus is on us.”

In reality, the onus is on all of us to have a more rational conversation. It’s important for the left to draw attention to injustices in Israel. And here at home. In fact, anywhere in the world. The right certainly isn’t going to do it.

In fact, in the most bizarre of circumstances, Christian fundamentalists have been some of the staunchest supporters of Israel, albeit for pretty shitty reasons. Again, Weisman:

“Christian fundamentalists saw the founding of the Jewish state and the gathering of Jews in the Holy Land as an important step toward the New Testament’s prophesied Armageddon and the eventual return of Jesus Christ. The Jews all might die, slaughtered in the battle of the faithful against the faithless, incinerated in the Tribulation or left behind by the Rapture… but for now, they were good friends.”

The alt-right, characterized by Richard Spencer, Nick Fuentes, Gavin McInnes and others, are less charitable than their evangelical soulmates. They outright deny the Holocaust and demonize Jews in every way imaginable. The vast majority of Republicans that don’t fall into these buckets are largely supportive of Israel because of its position as a proxy military and intelligence outpost for the United States. It’s difficult to imagine a more transactional relationship, which is why most secular and reformed Jews overwhelmingly vote Democrat, while the Orthodox and more conservative Jews have increasingly thrown both donations and votes behind Republicans.

Then there is the Black splinter group known as the Black Hebrew Israelites, who have been preaching on street corners in the Black community for decades.

“We came to America as slaves of various other lands because we broke God’s Commandments. The Lord had sent Chris, the Black Messiah according to Revelation Chapter 1, Verse 14 and 15, to die for us. He’s a Black man. It describes his hair, his skin color. Christians read that ago ‘no,’ although they’re reading his hair was like wool, his feet like it burned in a furnace. They’ve been preconditioned to hate. Despite the way we looked. But the message is redemption is coming.” -Bishop Nathanyel, founder of ‘Israel United In Christ’

Much like the Nation of Islam, it has managed to galvanize a corner of the Black community, and it’s their words mostly that are echoed in the most visibly disturbing antisemitic remarks that have recently bubbled to the surface.

The idea that Christ as a historical figure was indeed a person of color isn’t exactly new. The twist by the Black Hebrew Israelites is that Africans are among the true descendants of Jacob and members of the ten lost tribes of Israel. These tribes were spread through Africa and the Middle East and purportedly assimilated and lost to history. The Black Hebrew Israelites believe that they are among the lost tribes, as are the Japanese and Native Americans mind you. Geography be damned.

The central tenet of their belief is that Christ will return to Earth to enslave and then destroy the white race. Which sounds pretty un-Jesus like to me.

And, honestly, that’s why I can’t go much further into the history or illegitimacy of the Black Hebrew Israelites. Fighting over the providence of ten tribes that may or may not have existed is as ridiculous as arguing over the legitimate claim to Mohammed by Sunni and Shia Muslims, whether Joseph Smith found gold tablets bearing the world of God in fucking upstate New York, or if Xenu brought life to planet Earth 75 million years ago in L. Ron Hubbard’s space opera.

Yes, I’m agnostic, so that doesn’t help. But, more importantly, theocratic discussions weigh down any practical dialogue about the human condition as it is in the here and now. If your go-to move when stuck for an answer in a debate is to reference texts that were written 2,000 years ago, then you have a here and now problem.

Suffice to say, the Southern Poverty Law Center dubbed the Black Hebrew Israelites a hate group.

Bringing it home.

The evolutionary alchemy of James Baldwin, Malcom X, Kwame Ture, Cornel West, with the unfortunate sprinkling of thoughts from the Hebrew Israelites and Louis Farrakhan, has twisted the relationship between Black and Jewish people in America into an unrecognizable and irreconcilable state. That is, if it’s allowed to stand.

Jewish leaders who cannot attend to the principle articles of the Jewish faith amidst any criticism of its homeland are doing a disservice to the Jewish people.

One can stand in support of a Jewish homeland and, in fact, admire the enduring tenacity of the Jewish people while criticizing the far right elements of Israeli society that actively oppress the rights of a people. As Cornel West has said, “Marcus Garvey was a Zionist. Du Bois was a Zionist. King was a Zionist.” Even Booker T. Washington urged his people to “imitate the Jew.”

There is more to say about Israel, and in time we’ll get there. But it’s important to highlight how Black Americans have been in the vanguard in criticizing Israel. Or, as Chappelle would say, “We’ve been on that.”

But this is also where influential Black figures like Chappelle are getting it dreadfully wrong. Chappelle has transcended the world of comedy and taken on the status of social commentator. Through humor, yes, but his words carry meaning. His carefully crafted monologue recently on Saturday Night Live left everyone but Jews wondering whether his words carried antisemitic undertones. This monologue has been viewed tens of millions of times online already. So, it’s more than a routine. It’s a matter of public record and has altered the narrative.

His standard defense is fair. In comedy, it is taboo to punch down, as they say. But Chappelle has indicated that as a Black man in America, it’s not possible to do so because the Black experience in America remains firmly at the bottom. I won’t take issue with this, though I imagine many of my native friends would like a word. He worked this defense into the middle of the monologue by offering a solution to a problem that doesn’t exist:

“I know the Jewish people have been through terrible things all over the world, but you can’t blame that on Black Americans. You just can’t.”

I’m sure it appears selective to single this out, but to me this poignantly introduces the point that I wanted to bring to light. Jewish Americans were responding to a real threat from one of the most recognizable people in America. Kanye West threatening to go “Death Con 3” on Jews. And Kyrie Irving sharing a link to a video that purportedly suggested the Holocaust didn’t happen. I say purportedly because I would never watch that, so I’m relying on reporting from The Times.

The point is that these aren’t innocuous. When prominent public figures circulate this kind of antisemitism, it has psychological consequences on the Jewish people, yes, but also on those who don’t know history. The headline readers. The average American.

Was Irving punished? Sure. Financially and reputationally. Was Kanye punished? He’s doing a fine job destroying his reputation and wealth. But look, for example, at who Kanye was rewarded by. Conservative interviewers like Tucker Carlson, Gavin McInnes, Piers Morgan, Alex Jones, Ben Shapiro, Candace Owens scored big time with each and every interview granted by Ye. They couldn’t get enough of it.

White Christians are loving every single second of this shit.

As much as every word I’ve uttered thus far is that of an outsider, and hopefully objective observer, let me return now to the lede, as I promised, and give you some insider information. As a white man in this country, I can assure you that this most recent fracture in the Grand Alliance is music to the ears of the white patriarchal establishment that propagates and thrives by pitting the lower classes and marginalized against one another.

Dave Chappelle isn’t offering a fresh perspective to the conversation. He’s unwittingly doing the bidding of the corporate state. The state requires this kind of animus between classes of people. Because, the moment the oppressed realize that the real Grand Alliance in America is, and always has been, between white men and Christian zealots, the balance of power will shift and alter the course of this nation.

It’s incumbent upon Jews to reach back and open the door to empower those who have been left behind. To recognize that the pillars of their faith are greater than the fealty they pay to structures of corporate power. Black Americans must resist the temptation to dismiss the Jewish experience in the world and see that the gains amassed by Jews in America are because the white Christian overlords have allowed it as a matter of convenience. It’s a tenuous relationship at best that white Christians would sacrifice at the first sign of inconvenience.

When Hitler’s emissaries asked the attendees at the Evian Conference in 1938 who among them would take Germany’s Jews, America remained silent, though it understood the consequences of its refusal. This isn’t ancient history. It’s American history. A history that is stained with the blood of Black people, built on the graves of the indigenous and only recently tolerant of the Jew.

Every moment of infighting among the lower and working classes of this nation, regardless of race, religion or culture, is another protracted period of oppression that serves to benefit white men… like me.

Here endeth the essay.

Max is a basic, middle-aged white guy who developed his cultural tastes in the 80s (Miami Vice, NY Mets), became politically aware in the 90s (as a Republican), started actually thinking and writing in the 2000s (shifting left), became completely jaded in the 2010s (moving further left) and eventually decided to launch UNFTR in the 2020s (completely left).