Healthcare: Sick In America.

This three part series attempts to answer some of the most pressing and complicated questions about healthcare in the United States. As one of the only industrialized nations without government funded, universal healthcare, there is a natural tension between providing patient-centered care and trying to turn a profit. We look at the history of healthcare and coverage and why the United States treats medical care as a fringe benefit rather than a human right.

AT A GLANCE:

Image Description: A greedy doctor counting a bunch of $100 bills while an older woman looks on in horror behind him.

Image Description: A greedy doctor counting a bunch of $100 bills while an older woman looks on in horror behind him.

Part One: U.S. Healthcare: America’s Hypocritical Oath.

Summary: Today, we’re doing some level setting on healthcare in the U.S.—a long requested topic. We navigate this unf*cking based on direct queries from the Unf*ckers, creating a baseline that helps establish a foundation for related features down the road and an understanding of the moving parts and shared language for the challenges we face. Stay tuned, as next week we’re going to delve deep into the Affordable Care Act.

“Fringe Benefit.” That’s how healthcare came to be regarded in the United States. Lumped in with meal perks, an extra day off, maybe a brand spanking new company car. The very idea that healthcare is even associated with employment should be problematic enough. Let alone the fact that it’s considered a fringe benefit instead of a natural right.

We’re going to do some level setting this week, then follow up next week and drill into problematic parts of The Affordable Care Act (ACA). It’s not going to be a series, per se, but the topic is just so overwhelming that it would be an exercise in absurdity to try and unf*ck the entire thing in one go.

So this is one of those baseline conversations that helps us establish a foundation for related features down the road, an understanding of the moving parts and shared language for the challenges we face. But it’s time to begin in earnest, and some of the measures incorporated into the Inflation Reduction Act offer a reasonable jumping off point for us to enter the fray.

I don’t think there are any huge ah-ha moments that will knock you on your ass. That said, it was an important exercise, personally, because it forced me to think about the moving parts of the healthcare industry more critically.

It’s also one of the most requested topics by our audience. In fact, for this episode, most of the resources I’m relying on came from Unf*ckers. In terms of level setting, I actually want to begin with a handful of requests to help frame the inquiry. These questions helped organize my path as I plodded through some insightful books and articles, demonstrating once again that this community is bright and curious and our process is truly collaborative.

For example, here are some questions posed by Unf*cker ‘Jean S.’ a while back:

-

Why is healthcare so expensive and complicated?

-

Why does this country spend the most for poor outcomes relative to other countries?

-

And perhaps the most impossible and intriguing question; isn’t it immoral to make a profit off of sick people?

‘James M.,’ a listener who has spent more than 30 years in healthcare, suggested that we break up the industry into several topics saying, “The U.S. does not have a health system. It has multiple organizations seeking to maintain their mission by being profitable or maintaining their bond rating and having a surplus.”

One of the crucial resources I dug into for this, and undoubtedly for every future essay, is one that James recommended titled The Social Transformation of American Medicine, by Paul Starr. If you’re in the field, my guess is you already know of it. It came out a few decades ago, but it was a Pulitzer Prize winning book that remains relevant to this day and contains updates to the original. James suggested that we examine the disparate distribution of care, how professionals are trained and the differences between employer funded insurance and the Great Society programs that care for the aged and indigent. We’ll hit on some of these.

He then recommended that we separate Big Pharma from the discussion to set it on its own, specifically as it related to the role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or “PBMs.” And on this, I must profess some professional jealousy. One of the very first folders I created for UNFTR was titled PBMs. One of my best friends who worked in the industry had given me chapter and verse on these companies, and their existence is beyond scandalous.

Strangely, there’s precious little written about their role in the world, which makes it hard to research, but tantalizing to cover. But I kept kicking that can down the road. So, while I was on vacation, I revived my notes and figured it was a good place to start. Then I opened my pod app and went to one of my favorite pods called Congressional Dish, by Jennifer Briney, only to find that she just did a remarkable episode on PBMS in July. My hat’s off on this one. Check it out when you have a chance. It’s episode 255, and it’s extremely well done, as all of her shows are. I digress.

‘Phil S.’ sent a detailed email to us a while back, and I have to give him props for the thought that went into it. Phil segmented the topic into six distinct categories:

-

Our disproportionate outcomes as it relates to wealth, ethnicity and disability.

-

The uniqueness of our employer based insurance system.

-

The politicization of healthcare.

-

The “fallacies, perverse incentives and opportunities for exploitative financial fuckery that would make Milton Friedman harder than Matt Gaetz at a quinceañera.” (Unf*ckers really know how to get to my heart.) Among the examples he offers is “inelasticity of demand among patients… a complete lack of price transparency reinforced by mysterious chargemaster lists… costs distorted by insurance companies… and asymmetrical power dynamics often exacerbated by the racial and gender dynamics that are too often present.”

-

Consolidation and corporatization in medicine to maximize profits at the expense of quality, personalization and compassion of care.

-

A dysfunctional system with no incentive to keep people well.

And one more. Unf*cker ‘Sam E.’ who offered a basic and biting truth: we need to improve the system to have more people not in need of healthcare than in need of it. “In our supposed free market model, healthcare is a self actualizing industry.” Sam sent in a long and well reasoned letter that ends with another doozy. How can we transform the system to focus our efforts on quality of life over length of life.

That’s just a sampling of the requests and direction we’ve received regarding healthcare over the past year. Nearly all of us come in contact with the healthcare system on an almost daily basis. Perhaps you’re ill or care for a loved one who is. If you’re healthy and employed, you might not think about it, but your compensation involves some sort of complex deductions that impact your take home pay and coverage should you be in need of it. Maybe you’re without insurance, and it haunts your subconscious knowing that you’re one catastrophic event away from bankruptcy, or worse. Whatever the circumstance, medical care in the United States is its own singular stress point that we experience differently than every other industrialized country in the world.

Like I said, too much to bite off in a single go. So the challenge is how exactly to begin. In that spirit, there’s no time like the present.

Chapter One

A Bandaid on an Open Wound

“This law that I’m about to sign finally delivers on a promise that Washington has made for decades to the American people… I got here as a 29-year old kid, and we were promising to make sure that Medicare would have the power to negotiate lower drug prices back then… Seniors are going to pay less for prescription drugs… we’re putting a cap, a maximum of $2,000 per year on prescription drug costs no matter what the reason for those prescriptions are… This is a godsend. A godsend to many families. And long overdue.” -President Joe Biden on signing the Inflation Reduction Act.

Let’s be optimistic for a moment and take Uncle Joe at his word. The Inflation Reduction Act shores up some crucial gaps in the ACA.

In a New York Times op-ed, Larry Levitt from the Kaiser Family Foundation called the medical provisions in the Act, “The biggest health reform initiative since passage of the Affordable Care Act… and the single biggest political loss the drug industry has sustained. Big Pharma is no longer invincible, which could embolden future efforts to expand the scope of the drug-pricing restraints.”

I think it’s a fair statement—if not a sadly painful one—considering almost nothing has happened to improve coverage since the ACA. Caps on insulin as well as out of pocket charges for seniors and the ability for Medicare to negotiate drug prices hit directly at some of the fatal flaws of the ACA that placed many plans out of reach and left Medicare woefully inadequate for many seniors.

But even Levitt acknowledges that, “As popular as their platform will be, its reach has limits. Drug-pricing restraints will not apply immediately or to everyone, and drugs account for less than 10% of health spending.”

So, we have to contextualize this, even if it pisses in the nation’s cornflakes. Yes, these provisions will be a “godsend,” as Uncle Joe referred to them, to many seniors. That’s a really, really good thing. But, on balance, because this bill is being presented as somewhat of a capstone to Obamacare and the Democrats are doing a victory lap, there’s a sense of finality to the whole thing. Like everything’s fixed. But it’s not. In fact, these provisions, while certainly an improvement on the existing healthcare infrastructure, simply codify the nation’s Rube Goldberg system of laws and agents who profit from a system designed to line the pockets of institutions. They are, dare I say… pissing in the ocean to warm it up.

This bill is an acknowledgement that the fight for universal healthcare is over, as far as Democrats are concerned. And that’s a troubling realization. Both the Senate and the House voted entirely along party lines, with King of Maine and Sanders of Vermont siding with Democrats and Vice President Harris casting the tie-breaking vote. I get it. This bill was really about salvaging as many pieces of Build Back Better that impacted climate change reversal as Joe Manchin would allow.

Speaking of Joe Manchin. If any doubt remained as to whether or not this was his bill, witness the moment after President Biden affixes his signature to the bill. Biden reaches across Senator Schumer to hand the pen to a surprised Manchin. A couple of ways to interpret this. One, Joe is a better politician than most give him credit for. Another is that it symbolizes an acquiescence of sorts. To the old ways of doing business. This is D.C. We do things a certain way here. The good ol’ boy way.

Manchin and Schumer’s respective staff hashed out the details in private, so the story goes. Folks like Sinema were brought along with the promise that Wall Street would be protected. So would the insurance companies. And the fossil fuel industry. While I could certainly go on, there’s someone with far more standing and experience who would do a much better job of explaining where this all falls short. Buckle up for Bernie. Here are a few excerpts from his speech on the floor of the Senate:

“Given this is the last reconciliation bill that we will be considering this year, it is the only opportunity that we have to do something significant for the American people that requires only 50 votes and that cannot be filibustered.”

“Does this bill make it easier for workers who want to join a union to be able to do so, or will they continue to be attacked by their employers, making it hard to form a union? No. This bill does nothing to address that reality.”

“Does this bill extend the $300 a month per child tax credit that was so important to millions of families last year? Does it address that issue?”

“Does this bill do anything to help us create a rational, cost-effective health care system which guarantees healthcare for all as a human right, something that every other major country on earth does? No. This bill does nothing to address the extraordinary healthcare crisis that we face.”

“Is there anything in the currently written bill to expand Medicare to do what some 75, 80% of the American people think we should do? And that is to expand Medicare to cover dental care for seniors, hearing aids, and eyeglasses? No. This bill doesn’t touch that at all.”

“Under this legislation, Medicare for the first time would be able to negotiate with the pharmaceutical industry to lower drug prices. That’s the good news. The bad news is that we will not see the impact of these negotiated prices until 2026. Four years from now. Why? Got me. I don’t know.”

“When it comes to reducing the price of prescription drugs on Medicare, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We could simply require Medicare to pay no more for prescription drugs than the VA pays. End of discussion. A rather simple solution.”

“In terms of the Affordable Care Act, this legislation will extend subsidies for some 13 million Americans who have private health insurance plans as a result of the ACA over the next three years. Without this provision, millions of Americans would see their premiums skyrocket, and some 3 million Americans could lose their health insurance altogether. This is a good provision. I support it. But let us not kid ourselves. The $64 billion dollar cost of this provision will go directly into the pockets of private health insurance companies that made over $60 billion dollars in profit last year and pay their CEOs exorbitant compensation packages.”

Bernie spends the next ten minutes eviscerating the giveaways to the fossil fuel industry and how poorly crafted some of the renewable energy incentives are. But, in these statements, you can hear a dejected Bernie Sanders, still a seemingly lone voice in the progressive wilderness, almost coming to grips with the fact that this bill might not be the beginning of something special, but the last blown opportunity of his career.

Sorry to be so fatalistic about this, because there really are some things to celebrate. But, when you dig in a little deeper, it feels like a pyrrhic victory of sorts. And, because it solves important pain points for a critical voting bloc of seniors and strengthens the position of insurers, hospitals, drug companies, manufacturers, providers and lobbyists, it feels like the book has been closed on universal healthcare. Again. For now.

Chapter Two

The Long Arm of Milton Friedman

In the next chapter, we’re going to talk about the giant forces that move the healthcare industry. It’s important to understand that spending on healthcare is now 20% of our nation’s GDP. There are several ways to parse GDP data, but nearly every method drives to the same conclusion when you tally it up. It’s our biggest sector. And it makes a lot of people a lot of money.

There was a time, perhaps a couple of occasions throughout history, when a move toward nationalized health care was more conceivable. When it was part of the Bull Moose platform under Teddy Roosevelt in 1912. As part of FDR’s package of reforms prior to the war. Under Truman just after FDR passed. LBJ came the farthest with Medicare and Medicaid. But since then, it has steadily moved out of reach.

Single payer has always faced opposition. In the beginning, it was from rather unlikely places in hindsight. But over time, the forces have become almost insurmountable. Before we dig into just how big these forces are in the next chapter, let’s have a philosophical discussion.

As usual, the countervailing narrative to a single payer approach is best illustrated by none other than Milton Friedman.

Friedman was prolific until the end, including a paper on healthcare published in 2001 just five years prior to his death. It’s worth expending some energy on this because his unerring dedication to the free market is evident, even in the sound logic of the paper that drives him to a most illogical conclusion. Let’s start with some hardcore logic from uncle fucknugget’s paper.

“No third party is involved when we shop at a supermarket. We pay the supermarket clerk directly: the same for gasoline for our car, clothes for our back, and so on down the line. Why, by contrast, are most medical payments made by third parties? The answer for the United States begins with the fact that medical care expenditures are exempt from the income tax if, and only if, medical care is provided by the employer. If an employee pays directly for medical care, the expenditure comes out of the employee’s after-tax income.

“If the employer pays for the employee’s medical care, the expenditure is treated as a tax-deductible expense for the employer and is not included as part of the employee’s income subject to income tax. That strong incentive explains why most consumers get their medical care through their employers or their spouses’ or their parents’ employer. In the next place, the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 made the government a third-party payer for persons and medical care covered by those measures. We are headed toward completely socialized medicine—and, if we take indirect tax subsidies into account, we’re already halfway there.”

Okay. So let’s pause and reflect on these basic suppositions for a moment.

One thing uncle fartknocker was very good at was boiling things down to consumable examples that make sense in everyday life. Let’s start with the correlation between services such as shopping for gasoline, clothes and groceries. It’s tempting to just let this pass because medical services can theoretically be boiled down into goods and services. But what this ignores is the variability of health care needs and diagnoses.

You don’t get a second opinion at a gas station. And shopping for clothes isn’t a life or death decision. The clerk at the store is delivering a predetermined quantity of items at a price often set by bureaucratic institutions that Friedman so loves to hate. There’s nothing free and floating about gas prices. The store clerk has no influence over where the cotton was harvested for a shirt. And food prices are negotiated well in advance on global markets unseen and hardly understood by the person at the checkout counter. No clerk went to four years of college, another four years of medical school and two years of a residency to qualify them to make a crucial shopping decision that might alter the course of your life.

So, no. They’re not the same.

But he does make an interesting point about third parties, which we’ll get to later. More to his point regarding tax deductions, this actually explains a great deal of the rise of third parties in determining costs and coverage of medical care in the United States.

Now, we’ll return to Milton in a moment. But, to address this point, I actually want to turn to Paul Starr’s Social Transformation of Medicine to explain what he calls “the accommodation of insurance” in America compared to the European model that developed simultaneously and very differently. Bear with me on this one. It’s a long passage, but it eloquently describes how and why the two paths ultimately diverged:

“The original European model began with the industrial working class and emphasized income maintenance; from that base, it expanded in both its coverage of the population and its range of benefits. The original Progressive proposals for compulsory health insurance had shared much of this orientation, except that the American Progressives had a distinctive interest in reorganizing medical care on more efficient and rational lines. The defeat of that early conception meant there was no prior institutional structure for health insurance when the middle class encountered its problems of paying for hospital costs during the 1920s and when the hospitals encountered problems meeting their expenses during the Depression.

“So, instead of an insurance system founded originally to relieve the economic problems of workers, America developed an insurance system originally concerned with improving the access of middle-class patients to hospitals and of hospitals to middle-class patients. The Progressive interest in group practice, capitation payment, and incentives for prevention was rejected, and an insurance system developed under the control of the hospitals and doctors that sought to buttress the existing forms of organization. This was the basis for the accommodation of private insurance.”

So, from inception, we can see a couple of different tensions. If we take Milton Friedman’s view on the world, no system should have developed. Any barrier between patient and provider should be eliminated. Depression or no depression. The market will work it out. That’s… well, that’s one view. The European model, that was expressly rejected in America, was to protect the patient. The American model was designed to protect the hospital.

The idea being that if the provider is secure, then access to care is as well.

There are arguments to be made on both sides of this equation, and I think it’s helpful to understand where these ideas were originally formulated. This one question—whether the patient or the provider is the foundation of the healthcare system—ultimately determined the trajectory of the entire system moving forward. We chose to build around the system itself rather than the patient.

Now, let’s go back to uncle dickcheese’s contention that government incentives in the American system favored the growth of private insurers, whether intentional or not. On this, he is 100% right. Once again, here’s Starr to clarify:

“The health insurance system was set up in a highly regressive fashion: first, because it was based on employment; second, because of the practices of community and experience rating; and third, because of the favorable tax treatment of private insurance. (The Internal Revenue Code of 1954 confirmed that employers’ contributions to health benefit plans were tax exempt; indirectly, this exemption constituted a massive subsidy to people who had private insurance policies.) In leaving out millions of Americans, the insurance system actually worsened their position because of the inflationary effect that insurance had on the cost of medical care.”

Let’s stay in this pivotal period to tease out some of the early detractors of a universal system in the U.S. because they might surprise you.

So we’re talking about the ‘40s and ‘50s. During and after the Second World War.

Very much in the grips and immediate aftermath of the Great Depression.

The beginning of the Red Scare.

And the precipice of revolutions in medicine from vaccines to medical devices.

Prior to this period, healthcare was almost feudal. Infection and disease worsened by the economic crisis of the Depression. Almost all research was privately funded by wealthy patricians. As Starr notes, “In the early 1900s, the budget of the Rockefeller Institute alone was many times larger than federal expenditures for medical research.” It was understood that there were multiple therapeutic uses for penicillin, but access to it was extremely limited. It might have been a medical wonder, but if no one could get their hands on it, then it really didn’t matter.

So Roosevelt set about supercharging the industry. Scientists were smuggled into the United States from Germany after the war, and Roosevelt knew that psychological and physical ailments brought on by the war would be a major concern. And so the money came rolling in.

When the industry was coming of age, and before it was beset by professional lobbies and corporate interests, there were other forces at play that aligned against a nationalized health insurance system. Roosevelt was out of runway on domestic policies near the end of the war, as the nation turned its attention to post war economic concerns. The Truman administration attempted to pick up the mantle of reform to continue the legacy with a national healthcare model, but he ran into interference from the outset.

As hard as Truman worked to codify a version of national coverage, the first line of defense was actually physicians. As Stephen Brill writes in America’s Bitter Pill:

“The AMA spent what in 1949 was an astounding $1.5 million to campaign against the plan, labeling it socialized medicine that would be the key to the arch of a socialist state, which would destroy doctors’ independent relationships with their patients and lead to doctors becoming government employees.”

There are a few factors at play here. First off, they were tapping into very real public fears surrounding socialism in the post-war era. It cannot be overstated just how popular a selling point this is, no matter how much sense socialized programs make. Americans have been so indoctrinated against any hint of socialism that it persists as a bogeyman to this day.

Closer to home for the doctors themselves was the fact that they were making real money and that they weren’t about to have terms dictated to them by a bunch of government bureaucrats.

Remember, during the Great Depression and even prior to that, doctors weren’t paid all that well. And, in hard times, they were last on the list. So, when private insurance through employer sponsored programs coincided with a population boom and advances in medicine and outcomes, the profession grew up rapidly. And it wasn’t about to give back the gains it had made in a very short period of time.

The other roadblock for a universal coverage scheme in the U.S. was actually put up by unions. Sounds counterintuitive, but employer sponsored healthcare coverage was a union invention. One of the greatest perks ever conceived, in fact. If the government suddenly offered competitive benefits to the entire population, a critical bargaining element that made union membership special would suddenly be nullified.

Back to Brill’s book America’s Bitter Pill:

“The reason the unions were against government-supplied health care had to do with a quiet decision made during World War II by Franklin Roosevelt’s National War Labor Board, a panel he appointed to enforce wartime wage and price controls. In 1943, the board ruled that fringe benefits—including health insurance—were not subject to wage controls, which prohibited an employer seeking to encourage workers to join or stay at his company from enticing them with higher pay. Under the board’s ruling, an employer could lure workers by offering to pay for health insurance, to be supplied by what would soon become a flood of insurance companies flocking into the new market. The decision motivated unions to oppose government intervention.”

I know we all want to point fingers and know who’s to blame today. And there’s plenty of blame and anger to go around. But it’s important to nail down our history and understand when the ball started rolling and who gave it the first push downhill.

Chapter Three

Stakeholders and Cost Drivers

Alright. So let’s talk about who’s to blame today. Because that was then and this is now. Why has this issue become so intractable? We know the talking points by heart from the Progressive movement:

-

We’re the only industrialized nation in the world without universal healthcare.

-

Healthcare is a right not a privilege.

-

We pay the most for healthcare with some of the worst outcomes among OECD countries.

-

Insurance companies and Big Pharma are raking in billions of dollars in profits.

Now, we’ve established that healthcare writ large comprises 20% of our nation’s GDP. Another way to look at that is there are a lot of people who depend on this industry to make a living. It’s not all going into shareholder pockets, right?

So, let’s talk about who exactly is at the table to try and understand who is actually negotiating how care is paid for and administered in this country:

-

Medical device manufacturers

-

Labor and service unions

-

Insurance providers

-

Family doctors

-

Nurses

-

Surgeons

-

The Catholic Church

-

Drug companies

-

Law firms

-

Non profit hospitals

-

For profit hospitals

-

Plastic surgeons

-

Cosmetic surgeons

-

Anesthesiologists

-

Pharmacy benefit managers

-

Pharmacies

-

Ambulance drivers

-

Tanning bed manufacturers (not a joke)

-

Vitamin and supplement manufacturers

-

And on and on…

Seriously. This is a partial list. And for every category mentioned, there is a big time lobby behind them.

Attempts have been made to deliver what they call “patient centric” care, particularly in the ACA. For example, tying hospital reimbursements to outcomes. Clawbacks on payments if patients are readmitted for issues after being discharged. Some financial considerations, such as the ones in the Inflation Reduction Act, that attempt to ease the burden on certain vulnerable populations.

But, for the most part, discussions surrounding reform revolve around ways to contain costs and increase access. In fact, those were the only guiding principles behind the deliberations surrounding Obamacare.

Before we get there, let’s drill into a few numbers to illustrate the sheer scope of financial incentives for private companies that are baked into our current system. Here are 12 companies, three major ones representing four distinct industries under the healthcare umbrella. Four companies and their annual profits for fiscal year 2021, to give you an idea of just how much money is at stake in the current system.

Medical Devices

-

Medtronic, manufacturer of an array of surgical products, from diabetes and cardiovascular to urology and orthopedics, produced a net income of $5 billion last year.

-

Abbott Labs, producer of consumer brands like Pedialyte and Similac, and scores of professional diagnostic tools and medicines, threw off $7.6 billion in profit in 2021.

-

And Stryker, manufacturer of everything from beds and PPE to surgical tools and medical implants, made a $3.4 billion profit.

-

And Theranos…just kidding.

For Profit Hospitals

-

HCA Healthcare Inc., based in Tennessee, has more than 200 hospitals and 2,000 care centers that produced a $7.7 billion profit in 2021.

-

California’s Kaiser Permanente hospital system, one of the oldest in the country, threw off $8.1 billion last year.

-

And Universal Health Services, headquartered in Pennsylvania, has over 89,000 employees and threw off $1 billion.

Insurance Companies

-

UnitedHealth Group posted $17 billion in profit for 2021.

Big Pharma

-

Pfizer had a big year, partly because of COVID, but it’s a perennial monster that threw off a whopping $22 billion in profit in 2021.

-

Merck made $7 billion last year.

-

And AbbVie, maker of the wildly successful arthritis drug Humira, also had a banner year with $11.5 billion in profit.

Total it all up, and that’s $99 billion in profit.

$99 billion in profit, split between 12 major healthcare companies representing Big Pharma, for profit hospitals, medical devices and health insurance. There are more than 2,000 brand name pharmaceutical companies in the United States. 6,000 hospitals. 6,500 medical device companies. And over 1,000 health insurance companies. Thousands of companies, millions of employees. 20% of GDP. When you begin to digest the magnitude of the economic impact contained within this sector of the economy, the resistance makes a lot more sense.

Chapter Four

Bring it home, Max.

A lot of thoughts on this one. Some, we’ll clarify further next week and in related essays down the road. But, I want to return to Milton Friedman first, before we close this chapter.

Friedman concludes that a voucher system is the only way to go. To completely eliminate any friction between provider and patient. Medical savings accounts, to be specific. As he says, “Medical savings accounts… would voucherize Medicare and Medicaid.” His theory is that if government incentives like tax breaks disappear for employers and the government gets out of insurance, with the exception of catastrophic care, then the market will resolve itself.

Friedman’s vision once again delivers us back to the industrial revolution days when men were men and took charge of their own lives. That time in our history when there were 60 million of us, each with a life expectancy of 48. But he goes there as well and credits—get this—“improvements in diet, housing, clothing, and so on generated by greater affluence, better garbage collection and disposal, the provision of purer water, and other governmental public health measures,” for extending the lives of Americans.

It’s hard to tell if he’s punking us or not. Everything he credits for extending our lives is the direct result of government programs and interventions into the so-called free market to restrain corporations from doing the most harm they possibly can.

Then he goes on to say that, “In terms of holding down cost, one-payer directly administered government systems, such as exist in Canada and Great Britain, have a real advantage over our mixed system. As the direct purchaser of all or nearly all medical services, they are in a monopoly position.”

Importantly, he sees this as anti-competitive and resulting in the suppression of physician wages. Of course, he doesn’t mention that general practitioners, surgeons, nurses and family doctors earn more on average in Canada than in the United States. Only top surgical specialists in the U.S. earn so much more than Canada or the UK that it skews the numbers. So, no. Countries with socialized medicine value the medical field more than we do. What they don’t have are outrageously profitable companies that rob the system of capital that could otherwise go to saving consumers money.

But, as I’ve said before when evaluating motives, Milton Friedman was not a bad person with ill intentions. In fact, he concludes his paper saying, “The first question asked of a patient entering a hospital might once again become ‘What’s wrong?’ not ‘What’s your insurance.’” Like almost everything else he tackles, Friedman has the right inputs and a well intentioned output, but something happens in the middle when he looks at it all, because he can only evaluate the data through the free market lens. And in so many key areas of life, the free market simply does not apply because there are human factors that intervene to infect the data.

Okay, so he’s been dead for 20 years. Other than my obsession with him, why bring him into the conversation, right?

Because his concepts continue to carry a lot of weight. Take, for example, voucherizing healthcare. That remains one of the most popular talking points among conservatives. John McCain ran against Obama on this premise. Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell tried to overthrow Obamacare when they took over Congress under the belief that a voucher system would be better. Donald Trump hinted at it but, as we know, he never had a repeal and replace plan. Because this shit is hard.

The real truth in the Republican Party is that they are celebrating the healthcare wins of the Obama and Biden administrations just as much as the Democrats. Because their donors are all the same.

When the Democrats blamed Kyrsten Sinema for eliminating the carried interest tax loophole in the Inflation Reduction Act, I just laughed. She’s a convenient foil. No politician outside of the Progressive Caucus members who really, really get this stuff understands the correlation between this provision and literally everything else in our economy.

Those profits we talked about before? The $99 billion dollars in net income last year from only 12 out of about 15,000 healthcare companies in the United States came from public companies. Companies that have grown so large through unstoppable mergers and acquisitions. Corporations that control entire regions of the nation’s healthcare. Drug companies that dangle the promise of extended life in the first three seconds of an ad, followed by 57 seconds of disclaimers. But only if you’re lucky enough to have the insurance. Preventive care?

Fuhgeddaboudit.

Those big public companies that throw off massive profits aren’t building care systems around patients. They’re building systems around shareholders. And who are these shareholders? Unf*ckers know. Officially 90% of all stocks are owned by the top 10% of income earners in the nation. They tell you that it’s pensioners and old people. 401k participants and grandmas. They’re lying. It’s the richest 10%.

When economists talk about profits, they call it “surplus capital.” Money made beyond what labor was paid to create a product or service.

Marxists call this wage theft.

Modern capitalists call it a human right, and they have the Supreme Court decision to prove it.

So which is it? Well, the answer, in my opinion, comes from Unf*cker ‘Jean’s’ opening query:

“Isn’t it immoral to make a profit off of sick people?”

That very simple question has a very straightforward answer. Yes. It is immoral. And, if we start with this premise, it changes every input, every data point, every next question.

From beginning to end, we built a system to care for the top 10% of the nation.

The Inflation Reduction Act adds more nails to the barn door during the hurricane.

The answers will always be wrong if the question is.

Here endeth the lesson.

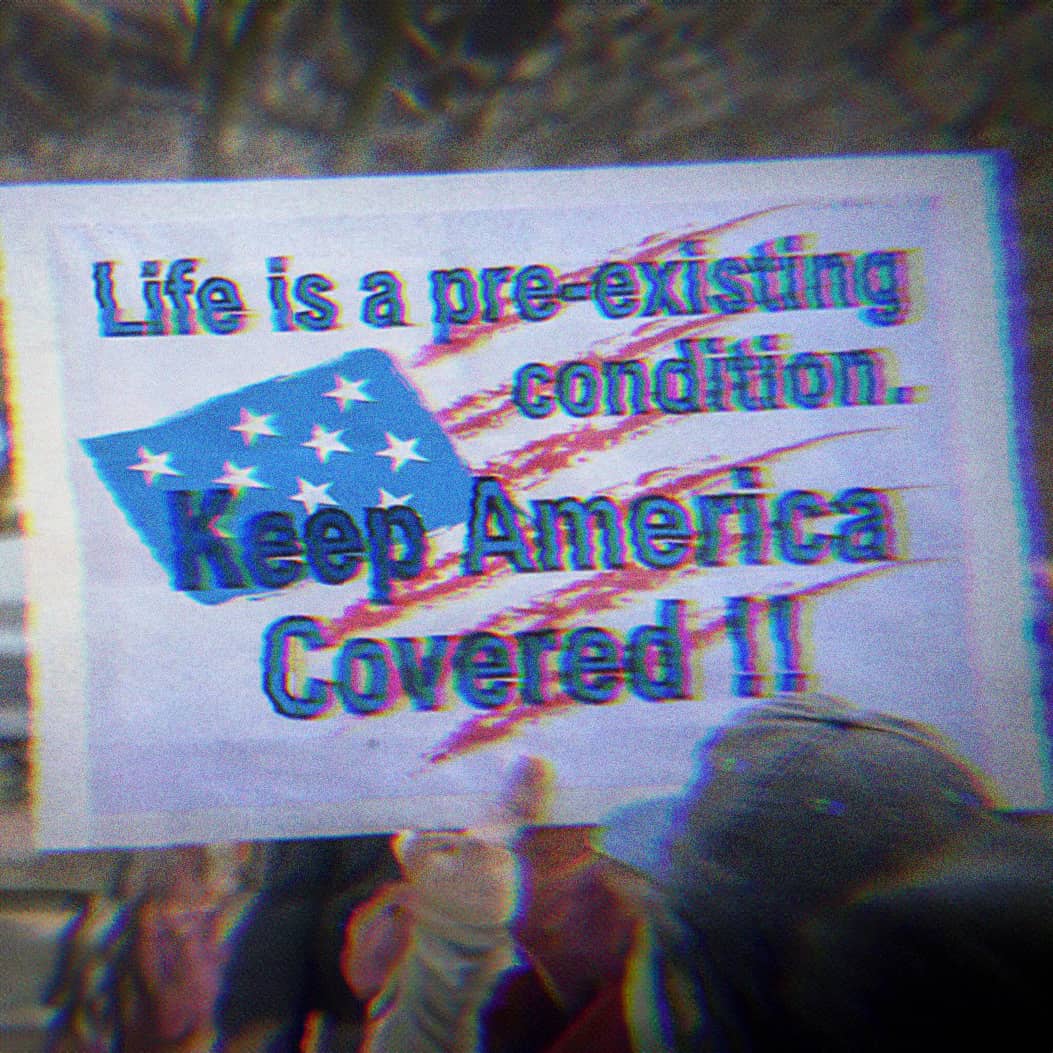

Image Description: Protest sign that says Life is a pre-existing condition. Keep America covered

Image Description: Protest sign that says Life is a pre-existing condition. Keep America covered

Part Two: This Healthcare Is Killing Us: The perpetual cycle of money madness.

Chapter One

Understanding the scope of healthcare.

The New York Times dropped an article this week detailing the rising U.S. mortality rate. A fall that Dr. Steven Woolf, director emeritus of the Center on Society and Health at Virginia Commonwealth University called “historic.”

From the article:

“It was the largest reduction in life expectancy in the United States over the course of a two-year period since the early 1920s, when life expectancy fell to 57.2 in 1923. That drop-off may have been related to high unemployment and suicide rates during an earlier recession, as well as a steep increase in mortality among nonwhite men and women.

“Although the U.S. health care system is among the best in the world, Americans suffer from what experts have called “the U.S. health disadvantage,” an amalgam of influences that erode well-being, Dr. Woolf said.

“These include a fragmented, profit-driven health care system; poor diet and a lack of physical activity; and pervasive risk factors such as smoking, widespread access to guns, poverty and pollution. The problems are compounded for marginalized groups by racism and segregation, he added.”

I want to thank the Times for the proper introduction to our second healthcare episode as we chip away at the American system, how it compares to others around the world and the unique challenges we face in repairing it.

There’s a general belief that the United States has the most inefficient and disparate level of healthcare among what is known as The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Unless you’re filthy rich, in which case our care is wonderful. But I digress. For clarity of process, OECD is just one of the acronym organizations that we’re relying on when contrasting systems, structures and outcomes across the world. And that’s a good place to pick back up on the topic and frame the discussion.

In terms of measurement, OECD nations aren’t the be all and end all. To start, this is an organization of 38 member nations representing Europe, the Americas and Pacific region. Naturally, there are a vast number of countries that aren’t represented. The purpose of using OECD nations as a benchmark is because the organization itself is a collection of countries with so-called market economies. There are corollary OECD working groups that draw data from non-participating or full member countries, but that goes a little further than necessary for our purposes.

I bring it up because the BRIC economies for example—Brazil, Russia, India and China—aren’t full members, but that doesn’t mean their systems and outcomes aren’t relevant to us. Like, it might be surprising to know that China has a market based insurance system. It works differently and nearly every citizen has what’s called Basic Medical Insurance, or BMI, but it’s important to understand there is parity in other places we don’t think of off the bat.

The other comparative area to explore is with respect to outcomes. And, as I mentioned in the prior episode, we’re relying on World Health Organization data because it has the most consistent 50 point benchmarking strategy over the longest period of time. Those are enough individual data points to be statistically meaningful, and the key element is, of course, a consistent trend line.

Assuming I’ve covered my ass enough, let’s get on with it.

All of which is to say, there’s no perfect way to go about this. The inputs and measurements matter. And no one country, just like no one patient, is the same. But if we’re to rely on global metrics, there are a few unmistakable signs that we’re on the wrong path here in the United States. Beyond the emotion and the politics, we have major structural issues. Not the least of which is spending for care per capita.

Despite spending the most per capita on healthcare by a wide margin, we have comparable to less favorable outcomes. (We’ll talk more about that a bit later.) And outcomes and satisfaction are two different things. In terms of satisfaction, how satisfied overall a country’s citizens are with healthcare access, affordability and quality, the U.S. really has a problem. When you compare it to a country like France, which regularly ranks at the top of the list in terms of satisfaction, we spend double the amount per citizen. These are the gaps that drive policy makers and medical professionals nuts. And yet, when policy measures are introduced, we seem incapable of asking the hard questions. Unless it’s Bernie.

But other politicians, like this guy running for office in 2008, recognized the problem using this very comparison:

“We spend more than other advanced nations on healthcare by a substantial amount. We spend about 50% more than France does on healthcare and yet they’ve got universal healthcare. A doctor will come to your house at 3 o’clock in the morning and prescribe you for what you need and you get it for free. Now, yes, you’re paying higher taxes, but what’s also happening though is they get a much more efficient system because they have more prevention and, as a consequence, regular check-ups, regular screenings, they save money and improve quality over the long-term.” -Barack Obama on the campaign trail in 2008.

What’s fascinating about this particular excerpt is how little of the candidate’s understanding of the problem actually made it into the proposed White House solution once he became President.

Because precious little actually came from the Obama White House.

Because it wasn’t his plan.

Because he didn’t have a plan.

The plan that is today known as Obamacare was originally known as Romneycare in Massachusetts and had, in fact, been circulating in conservative policy circles as early as 1989 by a Heritage Foundation associate named Stuart Butler. In fact, here’s Butler explaining the essential part of what he was trying to solve:

“It seems to me that until we get serious about a budget in the publicly supported—through tax or direct expenditures—the publicly supported parts of the healthcare system, we will never exert the pressure to make the tough decisions on how we actually get healthcare that we really need to do.”

Again, we’ll get to this when we talk about how the ACA came to be, but I want to recognize some of the language as we continue here. That direct tax he’s talking about is what became the so-called mandate. You know, that thing that caused Republicans to try and repeal and replace Obamacare countless times, and the very thing that the Roberts court in fact determined was a tax.

Now, importantly, Butler was trying to solve this not to expand coverage or improve outcomes, but ultimately to contain costs. He was attempting to devise a way to tax citizens and provide them with direct funds to manage their own healthcare needs. Very much akin to Uncle Nippledick’s (Milton Friedman, of course) idea of catastrophic insurance for all with individual spending accounts. Whereas Democrats ultimately embraced the plan, along with every other for-profit provider in the country, the original conservatives were trying to dismantle the entire system, especially entitlements like Medicare and Medicaid. Same inputs. Vastly different desired outputs.

All the seats at the table

It would have been impossible to do this series without a book I mentioned last time that an Unf*cker recommended titled The Social Transformation of American Medicine, by Paul Starr. At the very least, this would have been different. I want to share a passage that perfectly illustrates the tension that we discussed last piece because it will help us set the table for the two main areas that we’re going to focus on today, and that’s insurance companies and hospitals. Here’s Starr:

“The dynamics of the system in everyday life are simple to follow. Patients want the best medical services available. Providers know that the more services they give and the more complex the services are, the more they earn and the more they are likely to please their clients. Besides, physicians are trained to practice medicine at the highest level of technical quality without regard to cost. Hospitals want to retain their patients, physicians and community support by offering the maximum range of services and the most modern technology, often regardless of whether they are duplicating services offered by other institutions nearby. Though insurance companies would prefer to avoid the uncertainty that rising prices create, they have generally been able to pass along the costs to their subscribers, and their profits increase with the total volume of expenditures. No one in the system stands to lose from its expansion.”

This last point, the idea that everyone in the system stands to gain from expansion, is tantamount to understanding how our system developed over time and why the ACA codified, and in many ways bolstered, the standing of profit oriented organizations. As far as the “who” that Starr refers to, the “no ones in the system,” we gave a partial list last time, but let’s zoom out a bit to really drive this point home.

Again, not a complete list, but a much more comprehensive view of stakeholders in the system derived from a list of SIC codes, or the Standard Industrial Classification system in America. These are the ones who benefit from expansion, and they all had a seat at the table in designing the system even further under the Affordable Care Act.

-

Skilled nursing facilities

-

Assisted living facilities

-

Home healthcare

-

Chronic disease specialists

-

Medical research

-

Medical schools

-

Health care apparel and supplies

-

Inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation services

-

Laboratories

-

Obstetrics, osteopathy, oncology, ophthalmology

-

Pediatrics to podiatry

-

Medical malpractice attorneys

-

Dentists

-

Dental supply companies

-

Abortion providers

-

The Catholic Church

-

Oxygen providers

-

Insurance brokers

-

Tribal health services

-

Blood banks

-

Sperm banks

-

Prosthetics

-

Wheelchairs and accessibility devices

-

Hearing aids and eyeglasses

-

Plastic surgery, cosmetic surgery

-

Hyperbaric oxygen chambers

-

End of life care

-

Electronic medical record companies

-

Billing companies

-

Mental health care providers from psychologists to psychiatrists

-

Chiropractic care

-

Naturopaths

-

Physical therapists

-

Medical device manufacturers

-

General practitioners

-

Hospitals

-

Insurers

-

Collection companies

-

Pharmaceutical companies

-

Pharmacy benefit managers

-

Pharmacies

-

Independent pharmacies

-

Emergency care providers like EMTs and ambulance drivers

-

Anesthesiologists

-

Medical contracting and construction firms

-

Labor unions

That doesn’t include agencies like the VA or the myriad regulatory bodies that oversee each level of care. Or the FDA. USDA. Social Services. Medicare. Medicaid, etc. These are just the organizations largely incentivized by profit. The ones who only stand to gain from expansion. And every single one of them had a seat at the table when designing the system.

Chapter Two

The Insurance Class System

Insurance exists in other countries. Canada has private insurance you can buy to layer on coverage. China, as I mentioned before, has an insurance industry. Germany has private insurance to fill in gaps. But the most common thread among these other nations is that the baseline insurance is federal. Government insurance subsidized through taxation that automatically enrolls every citizen to cover preventive and routine care, emergency medical procedures and even long-term and chronic care.

In most other countries, private insurance can potentially cover elective procedures or low coverage areas like vision and dental. Employers and employees pay into the systems through deductions and the government supplements funding by taxing certain industries like alcohol and pharmaceuticals. Costs are primarily contained by the government setting the price of procedures, visits, prescriptions and the like. If you need a solid example to wrap your head around how it works, here’s one:

Medicare.

This is essentially how Medicare works, although the government has slightly less control over the cost of certain items like pharmaceuticals. That’s why it was such an important move to include negotiating power for prescription drugs and a cap on out-of-pocket expenses to seniors in the Inflation Reduction Act.

But, to keep things really simple, when we talk about universal healthcare in this country, it is not always the same thing as Medicare for All. I know that sounds obvious, but it’s a really important point.

Universal healthcare is what the ACA was driving at through a complex network of coverage schemes cobbled together to provide varying levels of coverage that differ from state to state. Medicaid for low income individuals and families. Medicare and its different parts for seniors. Employer based insurance. Exchanges for seasonal workers, gig workers, part-timers, freelancers or the unemployed to purchase healthcare. Special considerations for veterans. Tribal health services. Social services and nonprofits that receive federal aid and stand in for government programs, especially in areas concerning mental health.

All of which leaves the citizens of the United States in a rather precarious position. Depending upon your level of employment, station in life, age or occupation, it’s all different.

The insurance coverage scheme has created a class system in America. To address this, we have to talk about the Affordable Care Act.

While the ACA brought millions of Americans into coverage, gaps remain. As of right now, however, the percentage of uninsured Americans dropped from persistent double digits to around 9%. Not bad. Except that the number of underinsured is still much higher. And that 9% equates to 26 million people. (That’s the size of Australia’s population.)

Medicare is treated like a trophy in this country. Something you get for crossing the finish line of 65. And maybe that was a little more appealing before our fucking mortality rates started rising. (For a little context, countries like Japan didn’t see a rise in mortality during COVID, and every comparable nation recovered after initial drops. But not us.) So now we’re in a situation where we’re dying younger and finding it harder to afford quality care.

Another unique feature in the United States is the phenomenon of bankruptcies due to medical costs. A Kaiser Family Foundation report, in collaboration with The New York Times, conducted a qualitative analysis of medical debt and found that many who struggle with medical debt and file for bankruptcy had insurance. But the costs beyond their coverage placed them into debt.

Dead Kennedy and Dennis Kucinich

Despite attempts as early as the Bull Moose Party under Teddy Roosevelt and several administrations from FDR and Truman, Kennedy and even Nixon, the pursuit of a universal system of healthcare coverage has eluded the political class. Despite the overwhelming popularity for some form of universal coverage from a public option to Medicare for All, the political class has been unable to muster the momentum to pursue it.

First off, as we’ll examine below, there are practical reasons why a public option within the current structure isn’t really viable. And, to be clear, there are more in favor of this route than a Medicare for All. To understand the distinction between them, it’s instructive to look at the circuitous path the ACA took to becoming settled law in the United States. It’s ugly. And fascinating. And frustrating.

Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, Chris Dodd, John Edwards, Barack Obama and others were vying for the Democratic nomination in 2008. The real race was between Clinton, Obama and Edwards from the beginning, with most candidates withdrawing in January, including Edwards, and former Alaska Senator Mike Gravel pulling out in March. Only one candidate among all the Democrats running that year publicly endorsed Medicare for All. Dennis Kucinich.

But healthcare was a hot topic, and no one was more prepared than Hillary Clinton, who had the most time in the game from attempting to devise a universal coverage plan during her husband’s tenure in office.

The only candidate who didn’t have a plan, like at all, was (ironically) Barack Obama.

This is where Steven Brill’s detailed account of the ACA in his book America’s Bitter Pill really shines. He recounts the 2007 primary debate in Las Vegas where the candidates were pressed on healthcare, saying:

“The other candidates were crisp, knowledgeable, and specific, especially John Edwards, who freely acknowledged that he would end the Bush-era tax cuts for both the middle and upper classes in order to pay for expanded healthcare. And then there was Hillary Clinton. The New York senator stole the show. Her standing, strolling presentation was a tour de force of personal stories, sophisticated detail, easily understandable data, and great one-liners… Barack Obama, the former Harvard Law Review president and boy wonder senator, was not used to not being the smartest guy in the room.”

From this point forward, Obama would commit himself fully to understanding the magnitude of the healthcare problem and committing to many of the policies enumerated by his competitors, much to their great annoyance.

And yet, upon taking office, something remarkable happened. Full acquiescence. Once officially the POTUS, Obama had a stimulus package to work through Congress to save the imploding American economy. For better or worse, Congress was shockingly prepared to take the ball and run with it and the new president was all too happy to let this happen.

Brill provides a brilliant, almost minute-to-minute breakdown of what happened from this point to the passage of the ACA, the bill then Vice President Biden called a “big fucking deal” on a hot mic. (Actually, it wasn’t even a hot mic. My man was still at the fucking podium and said it with an Irish whisper to Obama.)

Anyway, while Obama was busy plugging holes in the economy, a few stars were aligning in the Democratic Party. First off, Ted Kennedy was dying. That sounded terrible, sorry. But this, too, was a big fucking deal because he was determined to make expanding healthcare his legacy.

Another senator, Max Baucus from Montana, was also interested in solidifying his legacy as a reformer after a lackluster career as a conservative Democrat. Baucus was critical, as he was the chair of the powerful finance committee.

The big question on everyone’s mind was whether or not any reform would be filibuster proof. In the end, this technicality didn’t matter, and we won’t get into the specifics of it today. But it was important at the outset because the Democrats came into office with 58 senators. Two away from being filibuster proof. Then, a miracle happened. Arlen Specter switched parties and Al Franken was finally elected after a contested recount. With Bernie, that made 60.

But first, the Democrats had to develop a plan. And then, herd the cats.

Chapter Three

Making the Sausage

As we dig into the considerations during deliberation over the ACA, just a couple of quick definitions.

MLR, or Medical Loss Ratio

This is essentially a way to cap insurance company profits. As Steven Brill notes, “The MLR is the ratio of claims insurers pay out to hospitals, doctors and other providers of medical care compared to the premiums they receive from customers who buy their insurance.”

On Wall Street, a low MLR was considered a badge of honor. A reason for investing in insurance companies. One of the most outspoken members of the newly formed administration was shit head Larry Summers, who worked behind the scenes to eliminate any talk of capping profits because, well, he’s a fucking asshole.

Age Band

This is an equation that determines how much older people could be charged relative to younger insured members.

Another important distinction in America. In most other countries, coverage is coverage. Even though it certainly costs more to care for seniors, most nations use the law of large numbers to spread the costs among the healthy population.

Federal Mandate

Ah, yes. The requirement to have coverage. This became the fulcrum of the debate. Forcing Americans to do anything doesn’t exactly land well in the court of public opinion. The idea here is to compel people to carry coverage or to tax them, which is ultimately what we wound up with. But in the beginning, it was absent from any White House talking points. And it was this element of the ACA that had its roots in the Heritage Foundation plan to essentially punish so-called freeloaders in the system.

Of course, this would inspire two things: 1) Upholding the ACA in court battles because it was considered a tax. And, 2) it would become a rallying cry for the burgeoning Tea Party and all subsequent opposition to Obamacare.

Adverse selection

The reason for the mandate is something economists refer to as “adverse selection.” Essentially, young, healthy people don’t feel the need to sign up for health insurance, and those are exactly the type of people that a plan needs to limit exposure and build numbers. Otherwise, exchanges would be filled with seniors and sick people.

This is how other countries are able to avoid things like the Age Band. And how they’re able to contain costs and negotiate rates. With everyone in the system, there’s enough money to go around to fund care and offer coverage. Everyone at the table understood that any plan would have to include millions of new “customers” in order to make the numbers work.

Public Option

This is a tricky one because it’s often confused with Medicare for All. Instead of the government taking over healthcare, it would provide a consumer option for a government run insurance plan.

The reason this never got off the ground is because it’s impossible to square with the private insurance industry. The only reason you would provide a public option is to allow people to buy into a system that purchases healthcare services at the same rate the government, basically Medicare, already enjoys. This would make private insurers completely uncompetitive. So fucking what, right?

So fucking this: Everyone from Baucus to Obama left it off the table in the initial negotiations because they knew too many of their colleagues who were in the pockets of insurers would balk at the plan. In the end, it was actually Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman who killed it once and for all when advocates insisted on including it. As Brill writes:

“The Connecticut senator finally got rid of the public option, including a version that allowed individual states to choose to implement it or not. Lieberman also shot down an alternative that would have allowed people 55 years old or older to buy into Medicare so they could be protected, but pay lower premiums from 2010 until 2014, when the exchanges, with their premium subsidies, would kick in.”

With some definitions and understanding of the scope, let’s recap a little.

At this crucial point in history when Democrats had 60 votes in the Senate, control of the House and a president who was embarrassed enough by Hillary Clinton and John Edwards to make universal coverage a lynchpin in his agenda, the stars were more aligned than they had been for decades. From the start, however, save for Bernie yelling from the wings and Dennis Kucinich proposing it from the fringe, no one was talking seriously about Medicare for All.

The only question now was how the Democrats would wrangle compromise from within its own party. And the person in charge immediately threw it to the herd to figure out. That meant the Senate primarily, with all of the special interest groups and state level interests, would be coming up with the plan alone. Even Nancy Pelosi and House Democrats were essentially shut out of the process. Time was of the essence, and the Senate began closing ranks. And the litany of self inflicted wounds was only just beginning.

Of course, there were external factors at play.

There is a now infamous story of a dinner where pollster Frank Luntz, Newt Gingrich, Mitch McConnell, Eric Cantor, Paul Ryan and Bob Corker, among others, gathered to devise a strategy to kill Obamacare right out of the gate, an insurance plan literally modeled on Romneycare, which was crafted and conceived by their beloved Heritage Foundation. Luntz and Gingrich were there because they were the authors of Newt’s successful Contract with America, the ten point plan devised to derail the Clinton presidency. They were experts at tanking public agendas.

They devised a public relations strategy, with now familiar talking points and framing, that would sit sideways in the ass of the American public. Phrases like “government takeover.” “Protecting the sacred doctor-patient relationship.” “Death tax and death panels.” And the ever popular “socialized medicine.”

“Keep government out of my healthcare” became a familiar Tea Party rallying cry happily stoked by Luntz and crew. And it was working. Every rally, every town hall that was interrupted, every angry Fox News commentator that hammered away at these points made a dent in the public psyche. And the longer the negotiations went on in the Democratic caucus, the more fearful the members became.

Senate Democrats, meanwhile, had a host of considerations on the table, each with a special interest group attached. Some would make it into the final bill. Many would be killed by said special interest groups.

Options like providing Americans the ability to purchase prescription drugs from Canada.

Nope.

Giving Medicare the ability to negotiate drug prices.

Nuh-uh.

The public option.

Sorry, Charlie.

Tort Reform.

Try again.

Cadillac tax on expensive plans subsidized by corporations?

A medical device tax?

Insurance company profit tax?

No, no and…no. But thanks for playing!

There were other considerations, like patent protection on certain drugs and therapies. What role the states would play in rolling out exchanges or providing their own plans. Whether abortion or contraception would be covered on plans sold through the exchanges. What was to be done about the Age Band, medical loss ratio and what would the character of the federal mandate be?

There was also the question of getting this thing paid for. Almost every candidate, and certainly the Obama White House, had run on the theory that expanding coverage through insurance exchanges would be budget neutral and eventually save the country money because so many new customers would be competing for healthcare, the market would respond by cutting costs in a more competitive environment.

How’s that working out?

There was also the question of subsidies. Setting up public exchanges didn’t mean that everyone could afford to buy into it. So they had to agree on a formula. Whether it would kick in for incomes 300% or 400% above the poverty line became a huge sticking point. And it made a huge difference in the high cost of living areas. Senate Democrats knew from the modeling that setting the limit at 300% above the line would still prevent millions from qualifying for subsidies. So, initially, they set it at 400%.

Then there was the political reality of getting it through Congress. For most of the negotiations, Senate Democrats operated under the assumption that they required all 60 votes to pass a comprehensive bill. In reality, this didn’t turn out to be the case because the ACA was ultimately considered a reconciliation bill and it didn’t require the 60 vote, filibuster proof threshold. This single point of view, taken as gospel from the beginning, meant that all of the special interests were able to negotiate favorable carve outs. And, by the time it was understood that 60 votes weren’t needed, the plan was so far along in the process that it was unfathomable to start over.

On top of this, there was bad news coming and challenges out of left field the team faced. As Brill writes:

“On July 17 [2009], the Congressional Budget Office announced what one of Obama’s healthcare aides called ‘a bombshell’... The CBO had just scored the House bill and declared that it would not result in any significant long-term healthcare savings.”

This was a disaster for Democrats, who were stunned by the CBO findings. Those intimately involved in the process went from using scalpels to hatchets to work the CBO estimates down to something resembling cost neutral. The longer the process went on, considering the economy was still in free fall, the less tolerance politicians had for spending. They were already about to propose a nearly $800 billion bailout plan. Anything more seemed like a bridge too far.

To complicate matters further, Obama had an unfortunate exchange at Ted Kennedy’s funeral, of all places. Again, Brill:

“One of the Catholic bishops in attendance bent his ear about abortion: The president risked the opposition of the church (and, by inference, legislators, particularly conservative Democrats in the House) if he didn’t make sure that no one got subsidized premiums to buy insurance that included coverage for abortions. There was even, he was told, strong opposition to insurance that paid for birth control.”

And we can’t forget about the Republicans. As a semblance of a bill began to take shape, Mitch McConnell introduced a poison pill by signaling their support for an amendment sponsored by liberal Democrats that would allow consumers to buy drugs from Canada. Fucking devious and brilliant. As Brill notes:

“On the merits, most Democrats loved importation. It would save consumers—and cost the drug companies—$400 billion over the next ten years… [Harry] Reid spared the dilemma of voting against something they favored. He refused to let it come up for a vote at all.”

In the end, the Senate would deliver a massive spending bill to the House with so many twists, turns, caveats and carve outs that Nancy Pelosi didn’t know what to do. She had been perturbed all along that the Senate was running roughshod over the House, but by the time the bill was sent, she had little choice but to corral her members and sign on, even admitting to the media that it was too long to read but that they would work out any details when the bills were paired. If you don’t recall this brouhaha, you can imagine how that went over in the conservative press.

Profits, profits everywhere.

Almost everyone in for-profit care got what they wanted. All except the doctors and the patients. In our final installment next week, we’re going to talk about hospital systems and comparative outcomes, but I want to finish with a few thoughts about insurance companies and the Frankenbill that is the ACA.

The reason a for-profit insurance based system is fucked from jump street is because of misaligned incentives. All the caps we talked about related to MLRs or Age Bands, or taxes on Cadillac plans and equipment, mostly went out the window in return for support from insurance companies.

To be clear, they did agree to a couple of important things. The insurance companies would have to pony up billions of dollars to compensate for the flood of new customers. Hospitals and pharma companies would as well. But, as many observers on Wall Street keenly noted at the time, no matter the size of these givebacks, the amount of new customers into the system was going to be a massive win for all the for-profit companies, bar none.

Eventually, the bill took so long to negotiate, the Democrats actually lost their majority when Ted Kennedy passed away and Scott Brown upset the apple cart to win the open seat, campaigning primarily against the pending federal mandate. This would prove to be a useful blueprint for Republicans in the midterms.

In fact, so many crucial financing portions of the bill had been cut by special interest groups along the way that legislators quietly changed the poverty subsidy threshold from 400% to 300% to protect the neutral CBO score.

Womp. Womp.

While there were a lot of winners in private industries, there’s no question that the insurance companies made out the best. All along, they had the most to lose, and they knew it. It’s why they were so early at the bargaining table and so willing to ultimately fork over $102 billion over ten years to help fund implementation of the ACA.

An insurance company isn’t incentivized to pay for patient care. As a for-profit entity, it has two incentives. Enroll as many people as it can at the highest cost possible and pay as little as possible for their care. It all goes back to this. Costs are almost meaningless. It’s what the so-called market, or several markets actually, will bear and who has the most leverage within the system.

For example, the entire underpinning of medical billing is an elaborate system of billing codes. Prescribe a drug. Take a urine sample. Order an MRI. Give out an aspirin. Take blood pressure. Perform open heart surgery. Do a hip replacement. Everything has a code, and that code has a cost. Except it’s not the cost. It’s a starting point. Like an MSRP for a new car. In a hospital, they call it a chargemaster, which has been a huge source of controversy ever since Steven Brill began writing a series of New Yorker articles before he published America’s Bitter Pill.

So your doctor—or the team in charge of your care in the hospital—will tally up every little thing that happens from room and board for pre and post-op recovery days to the nurse that takes your vitals. Then the negotiation begins. In a hospital setting, or in a large physician practice group or specialty group, there are tiers of strength. Big New York, New England, Chicago and California hospital systems get paid a lot closer to enumerated costs on the chargemaster than a small non-profit hospital in the midwest.

A physician specialty practice group has more power than an independent doctor. A group of doctors can command more than a sole practitioner, and so on.

Though, on the general practitioner side of things, even the groups are finding it nearly impossible to compete, which is why so many practice groups are being swallowed up by hospital systems. And when hospitals themselves consolidate, it usually means a reduction in the amount of beds. In fact, the number of hospital beds has declined precipitously in recent years. A reality that came back to bite us in the ass when COVID filled beds all throughout the country. But beds distributed throughout a region are difficult to manage. And expensive. So, if you can consolidate the big stuff under one roof on a primary campus and convert outlier hospitals to glorified emergency rooms that can transport serious care needs by ambulance or helicopter, it’s a lot more cost effective for the hospital.

And that’s the name of the game. Get big to get small. And charge the fuck out of the patient for everything under the sun.

We’re going to dive deep into the hospital systems in the next episode, but this gives a sense of where the problem really begins. With insurance and reimbursements.

Recall from our primer essay that profits in the insurance industry are extremely healthy. We gave examples of three of the big ones out of the nearly 1,000 registered providers in the country:

-

UnitedHealth Group posted $17 billion in profit for 2021.

-

Humana posted $3 billion.

-

And Anthem posted $6 billion.

All told, revenues for the health insurance industry topped $1.2 trillion dollars in 2021. (Those are yours and my premiums.) What’s important to recognize is that the profit margins aren’t exorbitant. In fact, margins overall range from 1.5% to 4% over a multi-year period. That’s not the issue. The issue is that they’re guaranteed.

They can’t lose because they set the rates, and the hospitals and physicians are incentivized to keep charging higher and higher costs to fuel their growth. It’s a vicious cycle that will be unstoppable, barring extreme intervention into the perverse market based system that only the United States operates under.

So, the final installment of the series will look at the cost drivers in hospitals themselves, along with some caveats for Big Pharma. While profits are greater in pharma as a percentage of revenue, the revenue picture is half that of the insurance industry, for some perspective. Overall, Big Pharma accounts for only 10% of total healthcare spending in the United States. So, we’re going to save the pharma analysis for another time when we unf*ck PBMs, patent protection issues and pricing of key drugs that strain a significant portion of the population.

For now, we’re going to stay focused on the two biggest drivers of cost—insurance and hospitals—because they feed off one another in a self perpetuating cycle of madness that will know no boundaries unless, and until, we someday get serious about Medicare for All. And, in the conclusion of the series next week, we’ll talk about a handful of necessary but Sisyphean steps that must be taken to get there.

The ACA wasn’t a bridge. It was a wall.

There’s no profit in a healthy population.

COVID should have been the catalyst.

Here endeth Part Two.

Bonus script from the audio version of this essay.

If UNFTR was a Big Pharma ad:

It’s the dawn of a bright new day in healthcare. Millions of Americans are rediscovering hope with a weekly dose of UNFTR.

Patient Testimonial 1: “After January 6th, I had trouble sleeping and focusing during the day. Then I started listening to UNFTR. And now I’m just fucking pissed off. All the time.”

Patient Testimonial 2: “For years, I thought I was losing my mind. Then I realized that it was the rest of the country that had lost its mind. Thanks UNFTR!

UNFTR reduces the pressure on the cerebral cortex, the part of the brain responsible for reason, language and learning. By exposing your mind to consistent bombs of truth, UNFTR works to reduce those “why is this happening?” moments and allows you to see clearly what’s really going on in the world.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: The clinical name for UNFTR is Unf*cking the Republic. Do not take UNFTR if you have a history of listening to conservative talk radio or alt right programming including Rush Limbaugh, Dennis Prager, Ben Shapiro, Michael Knowles, Candace Owens, Sean Hannity, Laura Ingraham, Tucker Carlson, Glenn Beck, Mark Levin, Dave Ramsey, Michael Savage, Charlie Kirk, Bill O’Reilly, John Stossel, Bret Baier and Sean Spicer. Mixing UNFTR with right wing propaganda may cause severe side effects like spontaneous combustion or explosive diarrhea. Studies have shown that consuming UNFTR over a long period of time may also result in an irrational hatred for Chicago School economists. Avoid UNFTR if you’re allergic to profanity or facts. Serious side effects may include screaming at your relatives over holiday meals, unfriending most of your high school friends on social media platforms and profound feelings of isolation and rage.

To help see the world clearly and meet people where they are, I take UNFTR. Ask your doctor if listening to UNFTR is right for you.

Image Description: A healthcare professional wearing scrubs and rubber gloves is counting a stack of $100 bills. The rubber gloves have blood on them.

Image Description: A healthcare professional wearing scrubs and rubber gloves is counting a stack of $100 bills. The rubber gloves have blood on them.

Part Three: Hospitals and Healthcare: From Sanatoriums for the Indigent to Citadels of the Elite.