Palestine: A Political History of Palestine from the 1880s through Today.

Max finally takes aim at the Israel/Palestine conflict with an introduction that frames the approach for the mini-series and sets guardrails for what will undoubtedly be an emotional journey for many UNFTR listeners. This episode answers why we decided to tackle this issue and how we’re examining it through a socioeconomic lens and Marxist view of history. It also dismisses two foundational deceptions pertaining to the larger narrative surrounding the conflict. This introductory episode concludes with several “level-setting” statements and a challenge: “If you can hold these thoughts in your mind at once, we can proceed.”

AT A GLANCE:

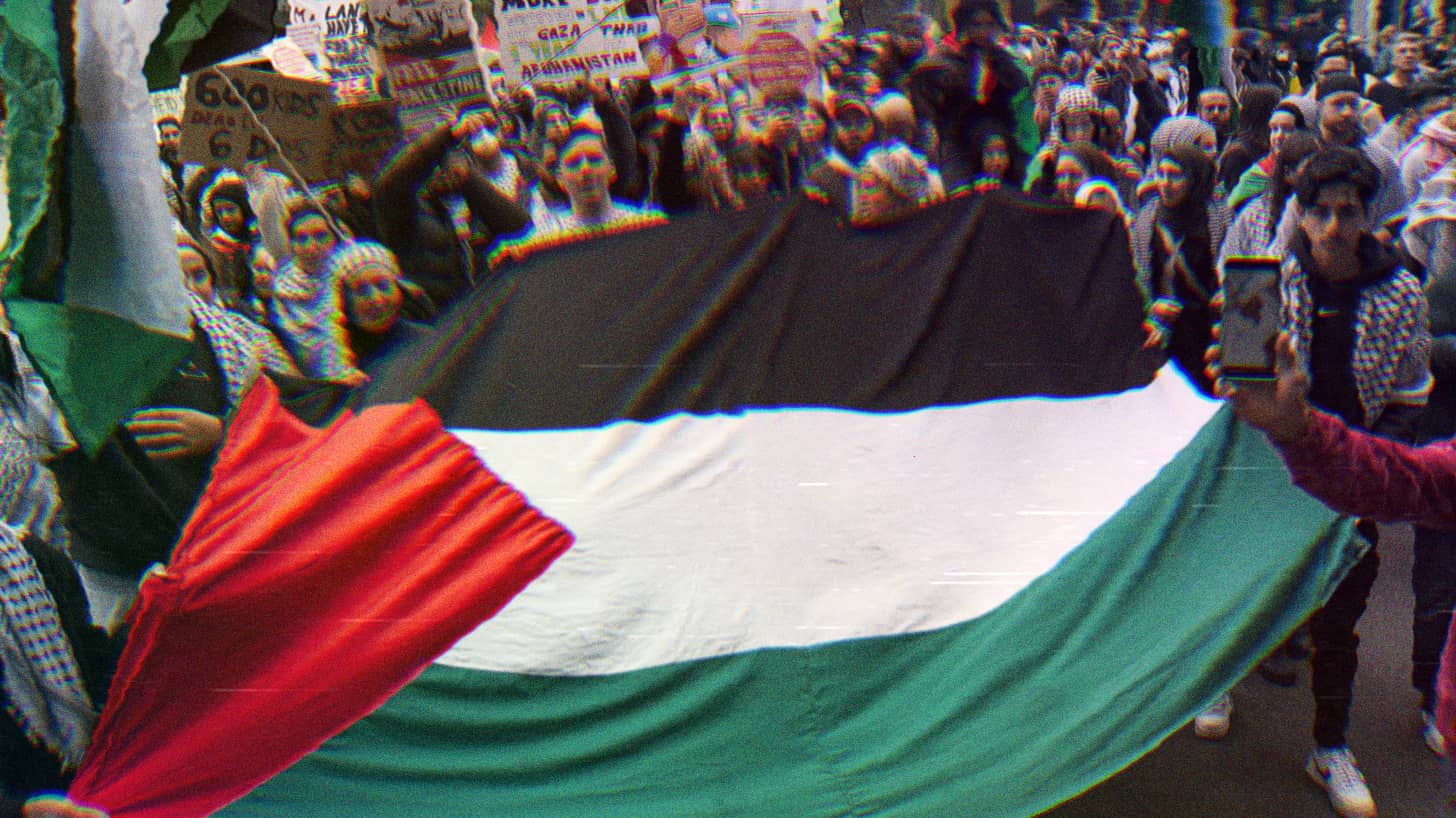

Image Description: A person waving the Palestinian flag.

Image Description: A person waving the Palestinian flag.

An Introduction: The Land Imperialism Left Behind.

Summary: Max finally takes aim at the Israel/Palestine conflict with an introduction that frames the approach for the mini-series and sets guardrails for what will undoubtedly be an emotional journey for many UNFTR readers. This essay answers why we decided to tackle this issue and how we’re examining it through a socioeconomic lens and Marxist view of history. It also dismisses two foundational deceptions pertaining to the larger narrative surrounding the conflict. This introductory episode concludes with several “level-setting” statements and a challenge: “If you can hold these thoughts in your mind at once, we can proceed.”

Editorial note: This essay is designed to set the table for subsequent shows that will cover the Palestinian conflict through a historical lens. Any viewpoints expressed along the way, which will be minimal, are mine alone. These entries into the record are not intended to take a stance or sway opinion. They are designed to inform and educate, and all reasonable feedback will be incorporated into our discussions moving forward.

The UNFTR audience is extremely small on the grand scale, but we are interconnected. You’ve given me your trust, and I’ve offered you forums to challenge my assertions and to connect with one another in meaningful dialogue. Most of us identify as progressives, though there are others who listen as part of their own learning journey and might identify on other parts of the political spectrum. On the whole, our exchanges exhibit a high level of empathy, and I expect nothing less moving forward. But it would be foolish not to acknowledge that tensions are running high and humanity is being challenged all around us at the moment.

I expect there will be further bloodshed and horror in the weeks ahead as we plod carefully through this exercise, that will seemingly render portions of these shows obsolete—or late, at a minimum. But the goal is not to provide some sort of magic analysis that, given a wider audience, would somehow positively impact the course of events. The goal is to provide our audience with the tools to discern fact from fiction and a safe space to air out our frustrations.

So, let us begin. What follows is a brief introduction to a series on Israel and Palestine that frames our approach and offers two important disclaimers to consider before we delve any further.

-MaxBeware the Origin Story

How should we interpret the rights of the descendants of Abraham over a patch of land to which they all claim dominion? Shall we speak to, as Christopher Hitchens wrote, “The apparent tendency of the Almighty to reveal himself only to unlettered and quasi-historical individuals, in regions of Middle Eastern wasteland that were long the home of idol worship and superstition, and in many instances already littered with existing prophecies.” I should think not.

The only way to speak plainly about the horror of war in Palestine is to literally ignore the original motivations of governments, religious groups and terrorists alike. Otherwise, we must concede the root of the disputes is simply too much to overcome, and that it will be God’s will to favor the victor. Namely, that each participant believes that their particular version of God favors them to such an extent that He would annihilate all others who lay claim to a false version. The most inscrutable notion ever concocted by mankind.

But, here we are again. Here we are still.

Each passing day, this conflict will change. Official stories will conflict with facts on the ground. The fog of war will shroud all rational discourse. The chorus of armchair correspondents on television and social media will pick and choose the version of events that suits them most, then reframe the narrative to fit the polling data. Or is it the other way around?

What role do we have to play in this never ending drama? Who are we to even have an opinion on matters that occur far away? Every pro-Israel or pro-Palestine post you make on social media is an indictor to the power base in the United States. And the power structure is listening. The United States holds more keys than we are willing to concede. Veto power in the United Nations. Weapons bear the symbols of U.S. corporations and of those we claim to be our enemies. Money flows ceaselessly from U.S. bank accounts to stakeholders in the region. We hold carrots in one hand, sticks in the other. Every U.S. president from Woodrow Wilson to Joe Biden has played a diplomatic role in negotiations.

Every demonstration is an expression of public sentiment that will ultimately find its way into the attitudes displayed by our leaders and the policy designs that follow. Every loose and ill-informed take is another brick in the wall between you and your fellow citizen. That’s why it’s imperative that we do the work to understand what’s happening in real-time, but in a historical context. We’re long past talk of isolationism. The Middle East is as much a product of our money and policy as it is the design of the Allied Powers after World War One.

The only end to the tragic story in Palestine will be the end of one half of it. Or the end of all of us.

So why even wade into these waters? What could I possibly offer to you about one of the most intractable conflicts in recorded history? I’ve had the words of an Israeli friend in my ears over the many months that I was preparing an episode on the Israel/Palestine issue: “How can you report on something you’ve never experienced?” It’s a valid question. One that I’ve thought a great deal about.

I wasn’t in Tulsa when white residents burned Black Wall Street to the ground. But I understand the implications of it.

Wasn’t around when Camilo Cienfuegos rolled into Havana in 1959.

Never hung with Marx and Engels.

Wasn’t there the fateful night economic neoliberalism was born as Milton Friedman defended the work of Ronald Coase, who claimed, “when transaction's costs are zero and rights are fully specified, parties to a dispute will bargain to an efficient outcome.”

I’m not a reporter. I’m a writer. The one who synthesizes the work of the chroniclers in the hope of providing perspective that empowers you to think critically about a subject. The difficulty here, of course, is that there are hundreds and hundreds of years of stories, perspectives, falsehoods, evidence, points and counterpoints and interested parties that span generations and empires, each of which have played a role in architecting the present state of affairs. All of it built upon Middle Eastern fictions and hearsay that have guided the affairs of man throughout history.

“Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, ‘Every man of you put his sword upon his thigh, and go back and forth from gate to gate in the camp, and kill every man his brother, and every man his friend, and every man his neighbor,’” cried Moses.

"Slay the idolaters wherever ye find them, arrest them, besiege them, and lie in ambush everywhere for them," said the Prophet Muhammed.

Holy books dipped in blood and the language of violence. ‘It’s metaphor,’ some say. Merely parables. You have to read it in context. I won’t wade too much further into these waters. I only offer this as a warning to steer clear of arguing with anyone who stakes a claim in origin stories.

And so, the best I can do is tell a story through our chosen socioeconomic lens and Marxist view of history. The best I can do is apply a secular interpretation as to why the corpses of teenagers and old people lay in Israel’s morgues. Why children’s limbs protrude from beneath bloody sheets on the streets of Gaza. The best I can do is take a step back and contextualize such atrocities with books and journals and historical accounts, knowing full well nothing will change so long as people choose to believe the same God somehow favors differing factions among his children and delights in the transgenerational bloodsport that has, and will ever thus, ensue.

Territorial Designs

I won’t patronize you with accounts of who stepped on what patch of desert sand when, and whether pig bones were found in an archeological dig here or there. This is a story about real estate. No matter the perceived original sins of the parties involved, the circumstances today are familiar to all who live in the post industrial world constructed by the imperial exploits of nation states.

Palestine has the unfortunate distinction of being the least conducive territory to nationalistic tendencies, and therefore the worst expression of them in a world that demands that we identify as such. Who are you if you do not belong to a nation? Who are you if you cannot define the borders in which you exist? Gone are the days of empire. This is the time of nation states. The Vatican can exist in the comfortable enclave of a predominantly Christian nation state. But what of Jerusalem? The Kingdom of David. Where Muhammed took flight on his night journey. Where Christ was crucified.

What is to be done with this most sacred land, whose infrastructure—from its hallowed walls to the aquifers and sewer systems—was constructed by Ottoman ruler Suleiman the Magnificent in the 1500s? He is as much responsible for the Jerusalem of today than anyone else in history, and yet there are no Ottomans left to lay claim to it because the Ottomans were Turks, Arabs, Jews and Christians. Members of empire. But we no longer live in the time of empires.

And what of the territories that surround it? When the dust settled from the Great War, the imperial forces of the allies blithely carved up the vast region of the Ottoman Empire and created new nation states that ignored cultural, ethnic and religious histories and manufactured Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq. Surrounding Jerusalem from Galilee to Sinai, from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, a no man’s land.

Palestine.

The French had designs on this territory, given its ties to the newly formed Syria. Winston Churchill, who famously bragged that he created Jordan with a stroke of a pen in an afternoon, considered it the domain of the British. The Jewish Diaspora had visions of a homeland for Jews who had been fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe even prior to World War One. The beleaguered nations that just endured a bloody and costly conflict that engulfed the continent and then some, simply ignored the fact that the land was already inhabited by a patchwork of indigenous farmers and villagers that roamed freely upon the land for generations. These people were never considered in the grand designs of imperialists. They were abandoned by their Arab brethren, who were busy building their new artificially designed territories. And they became a stumbling block to the Zionists who sought refuge in this part of the world.

The Central Thesis

Let me plainly state the central thesis of this analysis. While the roots of the Palestinian conflict are steeped in what I view to be nonsensical historical fictions, the present reality reflects a world that demands the artificial fealty of nationalism; further, the imperialist designs of superpowers, namely ours, reflect an inherent disdain for self-determination—along with poor and working class people—and exudes anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and racist structures of power that devalue human existence.

Nationalism has supplanted religion as the most dangerous development in history.

Now, before we go any further in subsequent episodes on the topic, there are two foundational deceptions we must address. This is the ultimate in level-setting, because if you cannot see past what I’m about to say, then there’s no point in moving forward.

Here are the two most pernicious underlying claims that undergird the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians.

The first is that there is no such thing as a Palestinian people. Theodor Herzl, a critical figure in this story, is widely considered the father of the modern Zionist movement. In his writings, the people of Palestine were referred to simply as “non-Jews.” But Herzl began organizing a movement well before World War One when there was no Israel, no Palestine and for that matter no Iraq, Syria, Jordan or Lebanon. There was only the vast Ottoman territory of the Middle East. Future Zionists would extrapolate the inference that the indigenous people of this territory simply were non-Jews, nameless and wandering, as they had no formal state as designed by the Allied Powers. It’s a false de facto claim that is as racist as it is ahistorical. But far right leaders of present day Israel from Menachem Begin to Benjamin Netanyahu would repeat this claim and solidify it into the far right ideology of the Zionist movement. Please note that I’m referring to it as the far right of Zionism, as Zionists themselves exist along a spectrum and are lazily portrayed as a monolith in western media.

But the words of Herzl themselves are evidence of the existence of the Palestinian people. More than a thousand villages and migrant farming camps between them existed throughout modern day Israel and Palestine. It’s only through the modern lens of nationalism that we would retroactively revoke their existence simply because they did not identify with a particular nationality; one that didn’t exist. They were Arabs who existed for centuries under Ottoman rule. Nationalism insists that borders lay claim to people within them and ignore historical patterns of migration. People in the United States should understand this concept more than anyone. Natives of this land are no less native because they were banished to the furthest, most resource poor areas of the continent. Such is the plight of the Palestinian people. If there are no historical records of Palestinians referring to themselves as such, it’s because there was no such thing as a Palestinian nation state. It’s the nation that didn’t exist, not the people.

Now, to the other side of the ledger: to those who say that Israel has no right to claim a homeland based upon a cultural and religious identity. One can reasonably litigate the attitudes and approach of the state of Israel toward the Palestinian people. One can even make the claim that the mere presence of a Jewish state nestled deep within a predominantly Muslim region is an invitation for disaster. But on this second point, one must also acknowledge the very real existence of anti-Semitism.

When Herzl and other Jews at the turn of the 20th century began crafting the plans for what could be a safe haven for Jews in the world, they did so because of persistent violent historical persecution. Among the scenarios they envisioned were Argentina, the Baltic region, west coast of the United States and, yes, Palestine. Of all the options, only Palestine offered what they believed to be a tangible connection to a shared cultural identity; a part of the world where Jews once thrived and prospered as a people. As the world repeatedly turned its back on the Jewish people while they were forcibly expelled from Europe, Jews weren’t exactly awash in options. And, as we’ll explore in the forthcoming chapters of this series, there was no guarantee that the Zionist experiment would come to fruition, let alone culminate in an independent state.

I’ve seen critics of Israel say that the Holocaust is not a blank check. While there are survivors of this atrocity who still exist and generations thereafter who are deeply connected to it, the Holocaust should not be viewed as an isolated incident. It was the most recent and unimaginable mass atrocity committed against the Jewish people, but certainly not the first.

Again, we can litigate the politics of Israel, the nation state, where the treatment of Palestinians is concerned. But to suggest that Jews are no different than any other culture or religion is as ahistorical as the notion that Palestinians aren’t a real people. The Jewish experience is singular. It's why I cannot, and will not, condemn those who believe in a homeland where Jewish culture and religion can not just exist, but thrive. Jews are different from every other ethnic or cultural identity on the planet, and I have all of recorded history to back up this assertion.

What I can easily condemn is the settler-colonial attitude of the far right in Israel that refuses to recognize the humanity of the people whose territory they occupy in defiance of international law, and the very tenets of a religion they profess to follow.

What must be agreed upon.

So, before we go any further, can you hold these thoughts in your mind at once?

“This is what you get” is not the same thing as “this is what you deserve.” Meaning, can you condemn the brutal actions of Hamas while acknowledging that they exist for a reason?

The life of a Palestinian is equal to that of an Israeli.

Palestinians are real and deserve the right to self-determination and the dignity of human rights.

Jews are not welcome in predominantly Muslim nation states, and safe harbor in western states provides no guarantee of safety.

The state of Israel has actively pursued a policy of apartheid governance in the region known as Palestine.

Hamas may have been an elected body that rose up against the Palestinian Authority, but it has devolved into a terrorist guerrilla organization.

That many of the nations surrounding the state of Israel have openly expressed a desire to eliminate it.

Just because your ancestors squatted in a mud hut two thousand years ago, does not give you the right to expel people from their land today.

And just because you live in a modern nation state, does not mean that you have the right to dictate terms of existence to people who wish to practice their religion freely or move about the world.

And finally. You. Do you understand that your actions play a role in determining the outcome of this current and future crisis? That you have an obligation to learn the history of this region and people before you post on social media, participate in a conversation or attend a demonstration? That blanket condemnation of one side or the other denies the humanity on both sides?

If you can hold these thoughts in your mind at once, we can proceed.

Image Description: Jewish National Fund stamp from 1915 with a drawing of the old blessing in Gan Shmuel

Image Description: Jewish National Fund stamp from 1915 with a drawing of the old blessing in Gan Shmuel

Part One: The Jewish Question.

Summary: Every story has a beginning. Every conflict has its roots. For some, the Israel/Palestine conflict is rooted in scripture and written in blood. Others claim it boils down to a deadly dispute over real estate. There’s a reason why “peace in the Middle East” feels out of reach and why so many have thrown their hands up. It’s complicated. But it’s not impossible to understand. We begin our journey in earnest by tackling the so-called “Jewish Question” and uncovering the roots and motives of the Zionist movement.

“The Jewish question is indissolubly bound up with the complete emancipation of humanity. Everything else that is done in this domain can only be a palliative and often even a two-edged blade, as the example of Palestine shows.” -Leon Trotsky, 1937.

You’ll forgive the brutish oversimplification of world history.

Finding a starting point in this journey is precarious considering we’re talking about the cradle of civilization. While we’re going to provide some cultural, religious and territorial background to the part of the world known as Palestine, the inflection point of our inquiry is an event in France in 1894. Not only does this year and specific event conveniently bridge our work in the socialism series, it is considered by many to be the birth of the Zionist movement. More on that in a bit.

First, let’s zoom out to identify the origins of the protagonists in our story: the Israelis and the Palestinians. These are modern nationalistic identities of Jews and Muslim Arabs who live in the territory between Galilee region in the north and the Sinai Peninsula to the south, and from the Jordan River in the east to the Mediterranean Sea. We’ll begin by examining what was widely referred to as “The Jewish Question.”

Chapter One: Diaspora.

The territory of Palestine and the modern-day nations that surround it were predominantly housed within a series of enormous empires throughout history. If we look at it in the Common Era, these territories were part of the Roman Empire and then the Eastern Roman Empire until they were absorbed into a series of Islamic Caliphates. Over decades and centuries, vast swaths of land would fall under dynastic rule within the major Caliphates, until the mid 16th Century when the Ottoman Empire consolidated much of these territories. Roughly, the Ottomans ruled from 1516 to 1918.

The Ottoman Empire is important to know, because the Jewish people found a safe haven here for centuries before the Empire crumbled during World War One. This area covers the Balkans down through Turkey, all of the Middle East to the border of Persia, or modern-day Iran, the Arabian Peninsula, and Egypt and Northern Africa to the border of Morocco. James Gelvin, author of The Israel-Palestine Conflict writes:

“As in the case of other early modern empires, religion provided one of the cornerstones of dynastic legitimacy in the Ottoman Empire. The empire was the preeminent Sunni Islamic empire of its time.”

At the center of it all, in the middle of three continents and all of history, lies Jerusalem.

Using the vast area surrounding Jerusalem as a focal point, we can bring in the experience of the Jewish people, beginning with the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. Until this point Jerusalem had been occupied, and at times controlled, by those who professed belief in Judaism, paganism and the newly formed Christianity. But, for the most part, it was just another important city in vast empires throughout antiquity.

In the centuries prior to Common Era, Jerusalem was both a secular and religious enclave that was swallowed up by Egyptian, Babylonian and Persian rule, and the Jewish people were among those who alternately resisted, but sometimes assimilated, into these empires. Of relative importance to this period is that the people of this land, including the Jews, were still polytheistic. But with the construction of the First Temple and the organizing of the Torah, the Jewish people began to consolidate their faith and mythology to create a unified identity. Note that I’m not using mythology as a derogatory term, rather to emphasize that the faith and traditions were cultivated over long periods of time into a singular narrative. What’s important is the idea that Jews began to build a distinct cultural and religious identity prior to their expulsion from this area after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

This is what gives us our first key term: diaspora. The term diaspora can be applied to any group of people with a common identity who are expelled from their native land. Today, we mostly refer to the Jewish Diaspora because of the very specific nature of the Jewish people, which will come into play later when we speak about nationalism. One of the reasons I referred to the Jewish experience as “singular” throughout history in the introduction to this essay is because Jews are the only people that can be identified by any combination of culture, ethnicity or religion. One can be Jewish but not religious or the other way around; one can convert to Judaism, but be of another heritage or ethnicity.

Throughout most of recorded history and even in antiquity, where many of our religious narratives have their roots, the Jewish people lived peaceably among other cultures and faiths, and under dynastic rule. The periods of persecution and expulsion that shaped modern Jewish traditions were few and far between, but tended to be brutal and all-encompassing. Most of us in western culture have a passing notion of the diaspora at the beginning of the Common Era because it represents the birth of Christianity and the modern calendar. The dominant monotheistic religions took shape under the yoke of the Roman Empire, and the rise of Christianity marked a seminal change in the course of western empires over the next few centuries.

Over the first half of the millennium, the Jewish Diaspora spread throughout the Mediterranean region from Northern Africa to the Iberian peninsula, where several Jewish communities thrived and Jewish people comfortably assimilated. Jews played a significant role on the Iberian peninsula, in particular, until the Visigoth rule that forced all inhabitants to accept Christianity by decree in 1492, the same year that asshole Columbus sailed the ocean blue. This is the population referred to as Sephardic Jews. Again facing expulsion from a region they had set longstanding roots, some sought refuge in Eastern Europe, and others within the burgeoning Ottoman Empire. And even before the Ottomans pushed further east, Jewish people also thrived in Arabic territories where Islam was already flourishing.

Chapter Two: Beyond The Pale.

When the Russian Empire started its historic expansion during the reigns of Peter the Great and Catherine the Great in the 1700s, many of the territories previously accepting of Jewish families quickly turned hostile. By this time, about 75% of the Jewish population globally lived in eastern Europe, mostly in what is modern day Poland. As Gelvin writes:

“The sudden appearance of large numbers of Jews within their empire was a matter of concern to Russian imperial elites. In 1791, Catherine the Great hit upon a novel plan to deal with them: Henceforth, Jews living within the empire were to reside in a specially designated area on the empire’s western fringes.

“The Jewish Pale of Settlement, as this area was called, stretched from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and included within its boundaries territories that make up the contemporary states of Lithuania, Belarus, and Moldova, and parts of contemporary Ukraine, Poland, and Latvia. The Russian government permitted Jews to live outside the pale only under special circumstances and only with special permission.”

Gelvin makes an interesting point about Jewish culture during this period that is worth noting. Throughout the long century from the establishment of the Pale and the turning point of Zionism, several laws were passed designed to target and isolate Jews in the Russian Empire. This included a conscription law bluntly titled, “Memorandum on Turning the Jews to the Advantage of the Empire by Gradually Drawing Them to Profess the Christian Faith, Bringing Them Closer to, and Ultimately Completely Fusing Them with, the Other Subjects of the Empire.” I shit you not, this was the title of the law. But back to Gelvin’s point:

“Because anti-Semitism did not distinguish between observant and nonobservant Jews, it had the effect of strengthening the belief within the Jewish community that shared history and culture, not religious belief or practice, made their community a community.”

This is such an important point to make, especially in today’s context, when we see so many secular Jews with divergent opinions on the state of Israel, where Jews belong in society and the Jewish faith in general. It’s critical to understand just how deep the ties are that bind the Jewish community together; ties that have held together a common identity for thousands of years, despite the absence of a homeland. Understanding the Zionist commitment to the state of Israel depends upon this historical appreciation.

This appreciation among the Jewish people of eastern Europe in particular is referred to as the Haskalah, otherwise known as the Jewish Enlightenment. Like the Enlightenment proper, this movement helped fuse science and reason with culture and was appended to the Jewish experience and traditions. Thus began a rational exploration of the Jewish faith, a quest to understand the Jewish existence in the context of both history and faith. This is similar to the early Enlightenment thinkers that we’ve covered who sought to contextualize their faith within political and economic doctrines. But for Jewish intellectuals, known as the maskilim, it incorporated the question of persecution. Why were Jews continually expelled and driven from lands where they not only assimilated culturally, but contributed to incredible societal gains? For the maskilim, the answer was found in the ancient texts, and the way forward was expressed in a concept known as Zionism.

In the Russian Empire during the late 1800s, Jews were being persecuted once again after being falsely blamed for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Pogroms spread like wildfire throughout the empire, and Jews once again found themselves seeking refuge in other parts of the world. In all, more than two million Jewish people fled Russia for parts of Europe, South America and the United States. But there were some who had a different vision. A dream of returning to a homeland to fulfill a prophecy. The Hebrew people’s return to the land of Israel. The First Aliyah had begun. The Jews were coming home.

Chapter Three: France, The Birthplace Of Zionism.

Every nation is steeped in mythology. Hard edges are rounded off, exploits are glorified and combatants are martyred in the practice of building a national identity. For the Jewish people, the story of Israel took on something more than mythological status. It was prophesy.

“He will raise a banner for the nations and gather the exiles of Israel; he will assemble the scattered people of Judah from the four quarters of the earth… They will swoop down on the slopes of Philistia to the west; together they will plunder the people to the east.” - Isaiah, 11:10

“‘I will be found by you,’ declares the Lord, ‘and will bring you back from captivity. I will gather you from all the nations and places where I have banished you,’ declares the Lord, ‘and will bring you back to the place from which I carried you into exile.’” - Jeremiah, 29:14

Theodor Herzl was born into a prosperous Hungarian family in 1860. Though educated as an attorney, Herzl eventually landed work as a journalist and worked as a reporter in Paris in the 1880s. It was during his time there that he witnessed the Dreyfus Affair in 1894, whereby a Jewish officer in the French army was wrongly accused of a crime, publicly humiliated and stripped of his rank and sent to prison. The event, as we covered in our socialism series, sent shockwaves throughout Europe and contributed to the fear among Jewish people who were already on heightened alert from the rise of anti-Semitism. For Herzl and other Jews, if liberal and enlightened France proved unsafe for Jews, then nowhere would be.

As former U.S. envoy to the Middle East Dennis Ross writes in his book The Missing Peace, “Herzl authored a book, The Jewish State, in 1896 and founded the World Zionist Organization the following year, even while remaining largely unaware of the activities of Russians beginning to immigrate to Palestine—activities that included reintroducing Hebrew as the national language. Herzl lobbied world leaders to gain support for a Jewish state. He pressed the leaders of the Ottoman Empire, including the Sultan, to lift the restrictions they had imposed on Jewish immigration and land purchases in Palestine.”

Here is Herzl in his own words:

“The Jewish Question still exists. It would be foolish to deny it. It exists wherever Jews live in perceptible numbers. Where it does not yet exist, it will be brought by Jews in the course of their migrations. We naturally move to those places where we are not persecuted, and there our presence soon produces persecution. This is true in every country, and will remain true even in those most highly civilised - France itself is no exception - till the Jewish Question finds a solution on a political basis.”

To Zionists, the Jewish question was clearly answered in secular terms first, doctrinal terms later. And the matter of where was secondary to the matter of what. A homeland to the Zionist leaders meant a state, not simply a home. This distinction remains central to understanding the nature of Jewish settlement in Palestine, and a theme we’ll return to when we cover the period between the Second World War and present day.

For centuries, Jews lived comfortably alongside Turks, Arabs and Egyptians, most of whom were Muslim. Rashid Khalidi, author of The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, describes this coexistence through to the first decade of the 20th Century when, “a large proportion of the Jews living in Palestine were still culturally quite similar to and lived reasonably comfortably alongside city-dwelling Muslims and Christians. They were mostly ultra-Orthodox and Mizrahi or Sephardic, urbanites of Middle Eastern or Mediterranean origin who often spoke Arabic or Turkish.”

The Palestinian people prior to the First Aliyah—the term used to describe Jewish immigration to Palestine, and literally translates to “ascend”—occurred prior to Herzl’s declaration of a movement. Tens of thousands of eastern European Jews fleeing persecution in the expanding Russian empire had migrated to Palestine to form agrarian communities known as kibbutzim. Why Palestine, when the new world was accepting of Jewish migrants? For some, it was uncertainty. But for others, it was natural and more economical than starting over an ocean away.

In Palestine, they found other Jews as well as indigenous Muslim, Christian and Druze Arab populations. Moreover, many found meaningful work, though not as much as those in the First Aliyah hoped. Contrary to the modern portrayal of the indigenous population, the industrial revolutions and concepts of nationalism had already penetrated the region. As Gelvin writes:

“It was the obstreperous warlord of Egypt, Mehmet Ali, who introduced Palestinians to the techniques of modern statecraft during the decade-long (1831–41) Egyptian occupation of Palestine…For Mehmet Ali, this territory—also known as ‘Greater Syria’ (the territory of present-day Syria, Lebanon, Israel/Palestine, and Jordan)—was a prize worth fighting for. Occupying this territory would enable the Egyptians to control the commerce passing through the eastern Mediterranean…After the Ottomans, with British assistance, expelled the Egyptian army and administration from Palestine, not only did they retain many of the innovations introduced by the Egyptians, they expanded them.”

Even still, Palestine was rural and less developed compared to their European contemporaries. But it was far from the wasteland some make it out to be. Once the Ottomans expelled the Egyptians, they set about building railroads and planting crops such as wheat, barley, cotton, tobacco and castor oil plants. As Gelvin notes, “On the coast between Haifa and Jaffa, the process of recultivation was slower but still irreversible.”

Again, this isn’t to suggest that “larger Syria” was thriving in the same fashion as the European states; merely to demonstrate that it wasn’t dependent upon imperial rule and oversight in the same way many other colonized agrarian nations were when under the thumb of colonial rule.

Private Property

One of the Ottoman inventions in 1858 would ultimately come back to haunt the people of Palestine: private property. As we espoused in the socialism series, the two pillars of Marxism are the abolition of private property and internationalism. The advent of private property—again, we’re talking about productive agrarian land and not individual homes—meant that it could be controlled. More importantly to our story, it could be bought and sold.

The Jewish National Fund (JNF) was established in 1901 for the express purpose of purchasing land to protect the rights of Jewish settlers throughout the world. The 1858 Ottoman land code provided the ability to do just that, a distinction that makes this part of the world amenable to settlement. It’s also why modern Zionists can rightly claim that much of the land settled by Jews throughout the 20th Century was indeed purchased, and not stolen.

Moreover, because of the expansiveness of the Ottoman Empire, many of the larger land owners in Palestine were absentee Arab landowners. Some were financed by British authorities, others by French and Russian concerns. Regardless of the origin of their capital, they had little connection to the land in Palestine other than to view it as an investment. “When representatives of the Jewish National Fund came around offering top dollar for land on which to establish Jewish settlements,” writes Gelvin, “many did not hesitate to sell.”

As Herzl and others quickly mobilized the World Zionist Organization, they began looking for settlement options. Because the British had an early foothold in the region and were so intimately involved in Northern Africa, it took it upon itself to first offer Uganda. And, in fact, Herzl was open to the idea. But Palestine had a few advantages in the eyes of the Zionist movement.

First off, there were already Jews who had moved there in the First Aliyah. Second, the 1858 land code gave the JNF the ability to begin purchasing large tracts of land. Because of the preponderance of cheap but skilled Arab labor, this would enable the Jewish settlers to get up and running faster than anywhere else. And then there was the doctrinal narrative. With options foreclosing quickly in eastern Europe, and western Europe following a similar path, the Palestine option became the most expeditious way to safely move what would be hundreds of thousands of Jews. Not even Herzl, who died in 1904, could have imagined the catastrophic horror that awaited those who did not join the subsequent aliyot.

Chapter Four: A Congress In Search Of A State.

The First Aliyah occurred during a global economic crisis. As such, upwards of 65% of the first wave of Jewish settlers wound up leaving Palestine by 1902. Nevertheless, tens of thousands of settlers remained and assimilated into the culture and economy alongside the Arab population. As Gelvin writes, “The first aliyah also raises the always intriguing question of what might have been. During the Aliyah, there was an intimate economic relationship between Jews and Arabs.”

Many argue today over the term settler-colonial to describe the actions of the Jewish people in Palestine. But, at the formation of the Zionist movement, it was widely understood that this was indeed the mission. Here are the four main tenets that emerged from the First Zionist Congress:

- The promotion, on suitable lines, of the colonization of Palestine by Jewish agricultural and industrial workers.

- The organization and binding together of the whole Jewry by means of appropriate institutions, local and international in accordance with the laws of each country.

- The strengthening and fostering of Jewish national sentiment and consciousness.

- Preparatory steps toward obtaining government consent, where necessary to the attainment of the aim of Zionism.

The first is a clear declaration of intent. To colonize the land known as Palestine. A few thoughts on this. First off, colonial rule was a normal way to pursue territorial expansion. It was practiced by all of the imperial powers and even by empires before. Attempting to whitewash or minimize this takes away from the discussion. It’s the second part of the first declaration that proves more interesting.

“Colonization by Jewish agricultural and industrial workers.” Lost in modern discussions is the fact that many Zionists of the time were socialists and viewed Zionism through a utopian socialist lens. This plays a significant role in the formation of early governance in Israel and disputes between what is colloquially referred to as “labor zionism” and “land zionism”, something we’ll explore more fully when we cover the formation of the Likud Party in the 1970s.

The second declaration is interesting. “In accordance with the laws of each country.” If we think about this for a moment, it reveals an obvious tendency. Most of the proposed territories were not yet seen as countries. Therefore, the options were either regions within empires or fully formed nation-states. The former would ultimately inform the decision to settle in a territory that had yet to be claimed by imperial interests.

The third declaration is self-evident. To succeed, the Zionists needed more than a homeland. They needed an identity. Because Jews viewed themselves along a spectrum of culture, ethnicity and religion, there was no singular definition. Centuries of diaspora meant that Jewish culture mirrored their settled lands. Ashkenazi Jews from eastern Europe had little in common with Arabic Jews or Sephardic Jews, for example. Furthermore, it meant there wasn’t a shared language, a critical ingredient in establishing a national identity. And because religious adherence ranged from the ultra-orthodox to secular, religion alone wasn’t a determining factor. The modern nation-state requires defined borders, governing principles, shared language and an identity.

On the last declaration—“consent where necessary to the attainment of the aim of Zionism”—this refers to the consent of the nations that mattered in the imperial designs of empires and nation-states. For the Zionists, Britain would take the lead; but France, Russia, Germany and ultimately the United States would provide such consent at different but critical junctures along the way.

So, if aligning the Jewry of Palestine into a singular identity was of paramount importance to the Zionist movement, it begs several questions. Who ultimately immigrated to greater Palestine, when and where. In answering these questions, we begin to see the vision coalesce, albeit in fits and starts. Again, Gelvin:

“Although the first aliyah did not provide viable economic and social structures that would support the Jewish colonization of Palestine, the second and third aliyot, which took place in the periods 1904–14 and 1918–23 respectively, did. These two waves of immigration brought approximately 75,000 new settlers to Palestine.”

So, the First Aliyah had brought agrarian settlers from the Pale of Settlement and other regions of greater Russia to Palestine in the hope of settling farming communities. It was important to determine a degree of self-sufficiency among those who settled the kibbutzim. Those who stayed comprised the bedrock of the Zionist labor movement determined to bring a democratic socialist vision to life. The Second and Third Aliyot were of a different character, as Europe descended into the chaos of World War One and shortly thereafter. The conquest of labor turned to the conquest of land and brought Jews from all over who were determined to “make the desert bloom.” While still labor-minded at heart, these waves brought with them an understanding that this was it. They were a full generation into the Zionist movement, and this was to be their homeland. No more running.

The socialist-minded Jews who first settled Palestine were also beneficiaries of prior socialist experiments such as Robert Owen’s New Harmony. As Gelvin observed:

“If utopian socialism provided the immigrants of the second and third aliyot with a set of guidelines, economic imperative provided them with the incentive to apply them. As we have seen in the case of the first aliyah, it was all too easy for Zionists to grow dependent on Arab labor, which was both cheap and plentiful. But employing Arabs could only undercut the Zionist project. Not only would it inhibit the emergence of an autonomous, self-sufficient Jewish nation in Palestine, it would expand the pool of available labor, depress wages in the Yishuv, and discourage Jewish workers and artisans from immigrating to Palestine.”

Gradually, the nature of the farming homesteads changed from the communal kibbutzim to the cooperative moshavim that allowed for individual ownership within settlements.

As we’ll cover in the next essay, the wave of immigration during the Second and Third Aliyot was the true beginning of the fracture with the indigenous population in Palestine who were about to be both carved out of imperial conquests and left behind by their Arab neighbors.

These were the so-called “facts on the ground” that the Zionists sought to change. This is a popular term that is important to understand, as it is still invoked today in Zionist policy circles. Changing the facts on the ground means to shift consciousness through land ownership. For example, if Jewish settlers move to occupy a territory, then after a period of time, it becomes a fact; something that must be factored into future decisions.

Steadily altering the facts on the ground through land purchases, and then expansion, was an essential part of the Zionist strategy that worked for Arabs employed by the expanding settlements and the Jewish immigrants. But as immigration increased and Jews no longer required Arab labor, inequity started to eat away at the Palestinian people. But, beyond the facts on the ground, there was another seismic event that occurred in 1917 that produced consequences that remain to this day.

“His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

This statement is what is known as the Balfour Declaration, something you’ve probably heard a lot about in recent weeks. Arthur James Balfour, secretary of state for British foreign affairs, wrote the declaration in November of 1917.

On the eve of the war, the Ottomans made a gross miscalculation and sided with the central powers against the Allies in Europe. This was mostly a reflection of the power structure being centered in modern day Turkey, as the Turks and Germans were more closely aligned. The Balkans were also drawn into the conflict on the side of Germany, and these territories had far more in common with the Ottoman Turks than the imperial forces of the Allies, who were seen as a more of a threat to Ottoman sovereignty. On this point, they were correct. But the Turkish estimation of the German forces, spurred on by early victories, led to the miscalculation. Not only would this lead to the end of the Ottoman Empire, it would deliver their worst fears of imperialist exploits.

The British took Jerusalem in 1917, and immediately set about consolidating their newfound holdings in the surrounding territories. The Balfour declaration, therefore, had the dual purpose of both defining a new imperial outpost for the British and to satisfy the Jewish question that was subsequently dropped on its doorstep. At the conclusion of the war, with nascent Arab states having been drawn all around Palestine, the Palestinian Arabs suddenly found themselves in a no-man’s-land. And the only rights being granted within this nation-in-waiting were offered to the newly settled Zionists.

The League of Nations, the precursor of the United Nations designed around Woodrow Wilson’s infamous Fourteen Points, borrowed liberally from the Balfour Declaration when drawing up plans for British rule in Palestine. Here’s Khalidi:

“The Mandate not only incorporated the text of the Balfour Declaration verbatim, it substantially amplified the declaration’s commitments…One of the key provisions of the Mandate was Article 4, which gave the Jewish Agency quasi-governmental status as a public body with wide-ranging powers in economic and social spheres and the ability to assist and take part in the development of the country. Article 7 provided for a nationality law to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews. This same law was used to deny nationality to Palestinians who had emigrated to the Americas during the Ottoman era and now desired to return to their homeland. Thus Jewish immigrants, irrespective of their origins, could acquire Palestinian nationality, while native Palestinian Arabs…were denied it.”

A confidential memorandum from Balfour himself, declassified 30 years after the war, lays the plan out in stark terms.

“For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country…The Four great Powers are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.”

The British Mandate encouraged a new wave of immigration, or the Fourth Aliyah, beginning in 1924. Over the next five years, it’s estimated that an additional 80,000 Jews migrated to Palestine, with more than half of them fleeing from new waves of anti-Semitic legislation and actions in Poland. As Gelvin writes, these settlers were, “more akin to refugees than their ideologically inspired predecessors…Many were small businessmen and shopowners. As a result, most did not subscribe to the socialist principles of the second and third aliyot.”

One of the most important figures in the Zionist movement emerged at this time. David Ben-Gurion, who would eventually be tapped as the first Prime Minister of Israel, came to prominence within the Zionist Party and focused his efforts on building a coalition among the laboring classes to align them politically with nationalist tendencies. His philosophy is known as mamlachtiut. While it doesn’t translate perfectly to English, the essence of it was to move the Jewish people from a class to a nation, a notion of sovereignty and self-determination that revolved around both the Jewish identity and the labor movement.

As Nathan Yanai writes in the Jewish Political Studies Review, “Ben-Gurion’s argument entailed two almost tautological propositions: one, that the labor movement must identify with the nation at large and its primary interests; two, that the labor movement was, in fact, ‘the nucleus and the future profile of a new Hebrew people.’”

Ben-Gurion was part of the democratic socialist tradition of the Zionist movement. His was a watered down vision of settler-colonialism that saw the virtues in a Jewish-run state, but one that would absorb the full citizenry of the populated territory. Ben-Gurion ultimately fused his followers into a consensus party known as the Mapai Party, which became the dominant political force in Jewish-controlled Palestine from 1930, through Israel’s founding and through to the 1970s. The ideological underpinnings of the Mapai Party were more inviting prior to Israel’s founding than afterward, but the roots were very much guided by Ben-Gurion’s specific take on labor nationalism and the belief that the way of the kibbutzim could light the path forward.

Ben-Gurion is a giant among Zionists who have contributed to the mythology over decades. However, the wave of “New Historians,” a group of Jewish historians in Israel dedicated to examining the nationalistic myths of Israel’s creation, have cast some doubt over the intentions of Ben-Gurion and the Mapai Party in recent years. The New Historians take a more cynical view of Ben-Gurion’s motives, particularly with the use of the Haganah, the paramilitary force he helped foster prior to statehood; Haganah would eventually become the Israeli Defense Force (IDF).

Ben-Gurion will play a more significant role in the post-1948 essay but his contribution to the formation of the Israeli government cannot be overstated throughout the 1930s.

The Palestinian Arabs were running out of options on the table. The British were running the territory of Palestine under the British Mandate and unbeknownst to the Palestinian people, the surrounding territories had already been theoretically committed in secret agreements reached among the Allies during the war. In March of 1915, the British reached an agreement with Russia to annex the Ottoman capital of Constantinople. In return, the Russians would cede any claims to the oil rich areas of modern-day Iraq and Iran.

In May of 1916, the British and French signed a secret accord known as the Sykes-Picot agreement, which would theoretically divide up the entirety of the Ottoman Empire should the Allies prove victorious in the war. Newly formed Lebanon would go to France. The British would take control of Iran and Iraq. Syria, Jordan and parts of Iraq would fall under French supervision and trade routes would be established between the newly formed Arab states to favor their new imperial rulers. Historical ties to Christianity and Islam and now the influx of Jewish settlers into Palestine made Jerusalem and the surrounding area a little murkier and so the Allies simply punted on the Palestine issue and instead opted to consider it an administrative territory with multiple stakeholders but no one firmly in charge.

What could possibly go wrong?

For their part, as we’ll explore, many Palestinian Arabs had hoped to fall under Syrian rule. Others felt more of a kinship with Transjordan. But Syria now belonged to the French and Jordan to the British. And because Egypt had revolted against the British a decade prior, it had already declared independence in 1922 and wasn’t inclined to extend a hand to Palestinian Arabs as they had their hands full trying to build a nation of their own.

Chapter Five: The Fifth Aliyah.

25,000 immigrants of Jewish descent came to Palestine from eastern Europe in the First Aliyah.

40,000, mostly Russian socialist Jews came in the Second Aliyah.

The Third Aliyah saw a wave of 35,000 Polish and Russian Jews under the hope and full expression of Zionism under the British Mandate.

Fleeing Polish persecution in the 1920s, more than 60,000 Jews migrated to Palestine in the Fourth Aliyah.

In 1933, the Nazi Party took control of Germany. According to the Holocaust Encyclopedia:

“Between 1933 and 1941, the Nazis aimed to make Germany judenrein (cleansed of Jews) by making life so difficult for them that they would be forced to leave the country. By 1938, about 150,000 German Jews, one in four, had already fled the country. After Germany annexed Austria in March 1938, however, an additional 185,000 Jews were brought under Nazi rule. Many Jews were unable to find countries willing to take them in.”

In 1938, a conference was organized in Evian, France. Delegates from 32 countries were in attendance. President Roosevelt sent a friend from the private sector with no diplomatic authority to address the question at hand: who among the great powers of the world would take in the Jews. Implicit in the question was extermination. Only the Dominican Republic raised its hand. The Dominican dictator General Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina agreed to accept up to 100,000 Jews. Over the next seven years, a total of 645 Jews were granted safe passage.

The Fifth Aliyah saw 250,000 Jews flee the Nazi controlled parts of Europe for the haven of Palestine. It was all at once too much for Palestinian Arabs to comfortably absorb, and yet not enough for the carnage and horror to come.

The Holocaust began with isolation and persecution. Anti-Semitic laws were passed, and Jews had their homes and businesses confiscated. They were relegated to ghettos. As the Nazis advanced, the Jewish question became more intense. A mobile killing unit called the Einsatzgruppen was formed to deal with Jews in newly taken territories of the Russian Empire. These killing units were indiscriminate. Their orders were simply to gather Jews and communists in villages, have them dig trenches and then they were gunned down and poured into mass graves they had dug for themselves.

The German officials would blame the Jews for the expense of ammunition that was sorely needed on the battlefield. From the Weiner Holocaust Library:

“On 20 January 1942, leading Nazi officials met at the Wannsee Conference Villa in Wannsee, a south-western suburb of Berlin. The conference had been called to discuss and coordinate a cheaper, more efficient, and permanent solution to the Nazis’ ‘Jewish problem’. The conference was attended by senior government and SS officials, and coordinated by Reinhard Heydrich.”

This was the “final solution” to the Jewish Problem; the Nazi’s answer to the Jewish question. When modern-day Zionists speak of the Fifth Aliyah, this is what they’re referring to. The systematic annihilation of an entire people. When ghettoization didn’t work, they mowed them down. When that proved to be expensive and inefficient, they turned to mass deportation. When that wasn’t fast enough, the Nazi Party turned to the brightest engineering minds from the business community to devise methods to exterminate Jews en masse.

The delegates at Evian understood the implications of their refusal to absorb Jewish refugees. The nations of the world turned a blind eye to an entire people. The United States even passed legislation prohibiting Jewish refugee migration during the war.

Some call Israel and the partition plans that followed an act of guilt on the part of the European powers. But there’s an even more cynical view to be taken. The refusal on the part of the Allied powers of World War Two, and throughout the Nazi rule that preceded it, remained in place. While a great many Jews did ultimately immigrate to the United States and other parts of the world, the European powers didn’t extend the hand of their motherlands. They extended the hand of the imperial territory of Palestine. Guilt, it seems, has its limits.

I’ll leave you as we started with the prescient words of Leon Trotsky from a journal entry in 1940. One of the last before he was assassinated.

“The attempt to solve the Jewish question through the migration of Jews to Palestine can now be seen for what it is, a tragic mockery of the Jewish People. Interested in winning sympathies of the Arabs who are more numerous than the Jews, the British government has sharply altered its policy toward the Jews, and has actually renounced its promise to help them found their ‘own home’ in a foreign land. The future development of military events may well transform Palestine into a bloody trap for several hundred thousand Jews. Never was it so clear as it is today that the salvation of the Jewish people is bound up inseparably with the overthrow of the capitalist system.”

Image Description: Palestine Mandate Stamp, SG no. 92, 4 Mils, thin paper variety, issued 1927, depicting the Dome of the Rock.

Image Description: Palestine Mandate Stamp, SG no. 92, 4 Mils, thin paper variety, issued 1927, depicting the Dome of the Rock.

Part Two: The Palestinian Cause.

Summary: Part Two of our series on Israel/Palestine turns back the clock to examine the time period from Part One but from the Palestinian perspective. By establishing the foundation of the conflict in parallel, it helps organize internal and external events that explain sympathies toward Jews and Palestinians alike. This episode digs into the cultural underpinnings of Arab society in the 19th and early 20th centuries and examines the fault lines that occur as a result of Jewish migration, industrialization, the collapse of Ottoman rule and fallout from World War One.

Joan Peters was a freelance journalist who developed a “fascination” with the Israeli/Palestinian conflicts in the 1970s and ‘80s. The publication of her bestselling book From Time Immemorial was an instant sensation that seemed to settle—in the minds of her western audience at least—the debate over the rights of Palestinians to the land in Israel and Palestine. She even went on to loosely advise the Carter administration. Though met with derision in Europe from the outset, it was met with widespread critical acclaim in the United States and put Peters on the map as a serious journalist with the temerity to wade into one of the most misunderstood conflicts in human history.

Her claim that there was no such thing as a Palestinian people was so forceful and backed by scholarly claims, demographic research and first hand reporting from refugee camps that it changed the national discourse in the United States and affirmed the claims of the Zionist movement that sought dominion over the whole of Palestine. There was only one problem.

The book was a complete fabrication.

If you’ve been following the conflict closely these days or have been tuned to it for a while, you may have come across the name Norman Finkelstein. Finkelstein was the first American scholar to dig into the claims made in Peters’ book in his PhD dissertation at Princeton, debunking nearly all of its claims.

The mere mention of Finkelstein’s name enrages Zionists and pro-Israel sympathizers the world over. He was banned from even entering Israel for a decade. His PhD was delayed because he had trouble finding professors to read it critically. His career suffered as well as he bounced around institutions, failing to make tenure at any of them. Lauded in left-wing circles as a truth telling son of Holocaust survivors and principled academic; vilified by nearly everyone else in American society as a self-loathing Jew and terrorist sympathizer.

Figures like Edward Said and Noam Chomsky dug into Finkelstein’s claims and uplifted his work. Others like Alan Dershowitz and Peter Novick of U Chicago became mortal enemies. Nearly all of academia and the mainstream media ultimately came to the conclusion that From Time Immemorial was propaganda at best—a hoax at worst. The central conceit of the book—that the Palestinians never existed and that the small number of Arabs in the territory known as modern day Israel/Palestine were nomadic tribes that hailed from other parts of the former Ottoman Empire—endured in pro-Israel policy circles and, more importantly, in the minds of many Americans.

Both Peters and Finkelstein would wind up disgraced for different reasons surrounding the same claim. And while Finkelstein is experiencing somewhat of a resurgence on the left these days, he remains a marginalized voice and is still viewed as a traitor to Zionists.

I begin with this not to surface the work of Finkelstein or any other pro-Palestinian scholar or activist, but to highlight the tension that exists in all walks of academia, activism and punditry. Our propensity to favor propaganda over fact checking scholarship allows false narratives to endure. Jews control the media and banks. Palestinians aren’t real. If you’re Jewish and criticize Israel, you’re a self-loathing Jew. If you’re not Jewish and criticize Israel, you’re anti-Semitic. If you believe in Palestinian self-determination, you’re a terrorist sympathizer. If you’re Palestinian and believe in a two-state solution, you’re a Jew sympathizer.

Listening to facts and scholarship that challenges one’s beliefs is difficult and we need to allow space for as many people as possible who are willing to try. Thus, in Part One I attempted to contextualize Jewish migration to Palestine in the five Aliyot in the first part of the 20th Century. Similarly, the goal of this essay is to explain how the territory of Palestine developed during the same period and how the indigenous population came to identify as Palestinians and call for self-determination.

These first two level-setting essays mostly cover the birth of the Zionist movement and the turning point of 1948. I want to emphasize the titles of the essays for a moment as well before we move on. Part One is titled “The Jewish Question” and Part Two is “The Palestinian Cause.” The implication of both titles is that both Jews and Palestinians have been viewed reflexively as modifiers in a statement; always framed as a question or a cause. There’s something about this that diminishes the humanity of both groups in my mind. At the root of it, that’s what I’m trying to tease out in these first two essays. To go beyond the question or the cause and to see the humanity in the people caught up in this most intractable conflict.

Where it will get tricky and the tightrope walking begins is in the final essay beginning with the events of 1948. For Jews it marked the historic moment of official statehood. Palestinians refer to it as the Nakba, the great catastrophe. But for today, the Palestinian cause.

Chapter One: Origin Stories.

“It's not my analysis. I quote Ze'ev Jabotinsky. I quote Herzl. I quote every Zionist leader up to the 1940s, all of whom described their movement as a settler-colonial movement that had to destroy the resistance of the indigenous population. They had no qualms about saying this.” -Rashid Khalidi

This quote is from a lecture by Rashid Khalidi, the Edward Said Professor of Modern Arab Studies at Columbia University, who published The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine in 2020, one of eight books he has authored on the subject. His book begins with a personal family history of his great-great-great uncle, Yusuf Diya al-Khalidi, “former governor of districts in Kurdistan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria; and mayor of Jerusalem for nearly a decade.”

In the lecture supporting the book, Khalidi explains that he introduced the book with this anecdote specifically for American audiences because he found Americans unique in their perspective that the Zionist designs on Palestine weren’t settler-colonial in nature; moreover, they had bought into the idea that Palestinians didn’t really exist as an identity, narrative residue of Joan Peters’ From Time Immemorial.

In seeking to establish the identity of the people, he uncovered the personal papers of his ancestors from the mid 1800s through the turn of the century. Among the collections of books, letters and archival material he found a critical correspondence between Yusuf Diya and Theodor Herzl.

“Yusuf Diya sent a prescient seven-page letter to the French chief rabbi, Zadoc Kahn, with the intention that it be passed on to the founder of modern Zionism. The letter began with an expression of Yusuf Diya’s admiration for Herzl, whom he esteemed ‘as a man, as a writer of talent, and as a true Jewish patriot’ and of his respect for Judaism and for Jews, who he said were ‘our cousins, referring to the Patriarch Abraham, revered as their common forefather.”

According to Khalidi, a portion of Yusuf Diya’s letter has been used in Zionist literature where he proclaimed Zionism to be, “natural, beautiful and just,” and, “who could contest the rights of the Jews in Palestine? My God, historically it is your country.” And indeed he wrote that. But by unearthing the remainder of the correspondence, Khalidi noted that this was used to acknowledge a shared heritage and claim to the land but as a prelude to warn against the idea of an exclusively Jewish state. Yusuf Diya follows with:

“‘Palestine is an integral part of the Ottoman Empire, and more gravely, it is inhabited by others.’ He concludes his letter saying, ‘Nothing could be more just and equitable than for the unhappy Jewish nation to find a refuge elsewhere…but in the name of God, let Palestine be left alone.’”

Let’s reflect on a couple of important points within these sentiments. The first is the notion we expressed in Part One, which is the natural and familial relationship between Jews and Arabs of greater Palestine during this period. This isn’t to suggest that relations in this part of the world, or any part of the world, have always been harmonious. That’s a profoundly ignorant claim. However, it is accurate to suggest that for hundreds of years in Palestine, people of varying ethnic and religious backgrounds lived in relative peace. Upper classes within each group thrived economically and were highly educated. There were competent administrators from all backgrounds that worked cooperatively under Ottoman influence to govern disparate territories. More to the Palestine cause, there were indigenous people of the territory referred to as Palestine, composed of modern day Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel and Palestine.

Yusuf Diya’s letter was somewhat prophetic in another respect. As Khalidi writes:

“The former mayor and deputy of Jerusalem went on to warn of the dangers he foresaw as a consequence of the implementation of the Zionist project for a sovereign Jewish state in Palestine. The Zionist idea would sow dissension among Christians, Muslims, and Jews there. It would imperil the status and security that Jews had always enjoyed throughout the Ottoman domains.”

This was both a fraternal and pragmatic warning. And it’s almost haunting when you consider it was written 124 years ago.

Incredibly, Herzl responded within three weeks of receiving the letter. His tone was just as deferential and cordial as there was a clear respect between the two men. But his words, while intended to be reassuring, seem dismissive in retrospect. Here is Herzl:

“‘It is their well-being, their individual wealth, which we will increase by bringing in our own…In allowing immigration to a number of Jews bringing their intelligence, their financial acumen and their means of enterprise to the country, no one can doubt that the well-being of the entire country would be the happy result.’ Herzl continues later saying, ‘You see another difficulty, Excellency, in the existence of the non-Jewish population in Palestine. But who would think of sending them away?’”

Let’s pause here because this is important. There are three things to unpack here. Critical aspects of myth building on both sides.

The first thing to note is Herzl’s claim that Jewish entrepreneurship and acumen would economically enhance the region and therefore all who live there. If we go back to Part One and reflect on the economic development of Palestine during the first three Aliyot, this sentiment rings true. The Jewish people brought important cultural and economic innovations to the region that helped foster its growth. Of this, there can be no doubt. It’s also true that like the colonial experience in the Americas, the indigenous populations passed on agricultural knowledge that helped facilitate this growth. It was a dynamic relationship that often inured to the benefit of both cultures.

As we also learned, however, as Jewish immigration intensified one of the aims of the more modern Zionists was to break free from the reliance on Arab labor. This also happened, so the benefits to the local population were as real as they were temporary. Especially as the Jewish National Fund, the British Empire and other Zionist organizations began to pour wealth into the region. These capital inflows throughout the 1920s in particular, exceeded 100% of the GDP of the region and allowed for extraordinary economic growth while the newly formed Arab states surrounding Palestine floundered under the imperial rule of France and Britain.

Then there’s the language that Herzl uses. “In allowing immigration to a number of Jews.” The tacit implication here is that there was already a structure in place to allow for Jewish settlement. In other words, there was already a local population in charge of regional administrative rule. Contrast this with the notion that Palestine was barely populated by non-native Bedouins in tents, and a clear tension emerges.

But it’s Herzl’s last point that stands out the most, especially because it was volunteered to Yusuf Diya. In his letter to Herzl, Yusuf Diya never raised the idea of displacement. And yet, Herzl wrote: “Who would think of sending them away?” This may seem trivial, but when Herzl’s letters and diary were published after his death, this sentiment expressed in his diary four years prior to his correspondence with Yusuf Diya paints a different picture:

“We must expropriate gently the private property on the estates assigned to us. We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it employment in our own country. The property owners will come over to our side. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.”

Herzl visited Palestine only once during his lifetime and passed away in 1904. But as he’s considered the father of Zionism, we must acknowledge both the impact of this sentiment and its strategic importance. While the Zionist project would be carried out by others over time, the idea that the indigenous people of Palestine would be henceforth considered simply “non-Jewish people” persisted and would be reinforced in the public consciousness from the Balfour Declaration through From Time Immemorial; a concept that endures to this day.

Chapter Two: Historic Palestine.

They were Muslims, Jews and Christians. Bedouins, farmers, merchants, fighters, administrators, clerics and educators. Persians, Arabs, Ottomans, Jews. For thousands of years the territory they inhabited was known by many names. The Caliphate. The Levant. The Fertile Crescent. The Ottoman Empire.

Palestine.

Home to the ancient cities of Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Mecca, Medina, Hebron and Damascus. But what of the people?

Khalidi said, “My grandfather’s generation would have identified in terms of family, religious affiliation, and city or village of origin. They would have been proud speakers of Arabic, the language of the Qur’an, and heirs to Arab culture. They might have felt loyalty to the Ottoman dynasty and state, an allegiance rooted in custom as well as a sense of the Ottoman state as a bulwark defending the lands of the earliest and greatest Muslim empires, lands coveted by Christendom since the Crusades.”

A people who identified with history, religion, family and language. And like every other person in the world, they would soon be swept up by the changing tide and hurricane winds of industrialism. As we said in Part One, this part of the world was slower to feel the effects of industrialization, but it wasn’t completely immune to it. Just prior to the post-Napoleonic period while Europe’s economy was rapidly expanding the Ottoman Empire, was in one of its waning periods, writes James Gelvin, author of The Israel-Palestine Conflict:

“The [Ottoman] government’s authority throughout the empire was increasingly challenged by local warlords. Two warlords of note emerged in Palestine. A warlord of bedouin origin, Zahir al- ‘Umar, took control over the Galilee region and established a principality with its capital at Acre. Further north, a former slave from Egypt, Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, took control over the port of Sidon (in present-day Lebanon) and established a principality that stretched into southern Syria.”

Eventually, the Ottomans settled the dispute by intervening on the side of al-Jazzar who established the cotton trade throughout Palestine. With the demand for cotton on the rise, this positioned certain cities in the region to join newly established trade routes in the fast modernizing world, and led to the build up of the cities of Acre in Galilee down through Jaffa, known today as Tel Aviv. The Arabs in the cotton trade would experience the same boom and bust cycles as their European counterparts, especially when the cotton trade took off in the United States. The interruption of the Civil War in the fledgling U.S. allowed for the markets in these trade ports to remain competitive at a critical time of development.

Again, Gelvin:

“The expansion of a market economy in Palestine enlarged what one historian calls the ‘’social space’ of its inhabitants, in effect changing their perception of their lived world as links between cities and countryside, and between inhabitants of the region and inhabitants of the world beyond, increased in number and importance. The expansion of personal horizons in Palestine, along with the appearance of an increasingly complex division of labor uniting the inhabitants there, was one factor that contributed to the diffusion of a culture of nationalism.”

These are important factors to consider through a modern lens that often casts this region as entirely backward and the people nomadic. Furthermore, as we noted in Part One, the governance of these territories took a more outward stance during Egyption occupation under Mehmet Ali. Forces from the south, or northern Africa would battle for hegemony with European empires that sought to lay claim to the fertile territories and ancient cities of greater Palestine from this point forward.

A passage from Studies in the Economic and Social History of Palestine authored by Roger Owen in 1982 sheds further light on the economic activity of this time:

“Alexander Schölch’s ‘European Penetration and the Economic Development of Palestine, 1856-1882,’ makes a number of interesting points. Foremost among them is Palestine’s remarkable economic upswing prior to the beginning of substantial European colonization in 1882. Palestine’s agricultural production and import-export trade activity grew, as did its towns and urban production. Much of this growth was a response to increasing European interest in the country. But European demand is not the full explanation, since internal Ottoman markets (including Egypt) also stimulated production of Palestinian agricultural and manufactured goods. Schölch calculates that Palestine had a trade surplus in most of the 1856-1882 period, counting foreign and intra-Ottoman trade together.”